Why Labor Mobility?

The ‘Why Labor Mobility?’ series of policy notes explores the historic need for labor mobility from the lens of key actors:

- receiving countries

- sending countries

- employers

- workers

- ‘mobility industry’

This fourth note in the series focuses on the perspective of foreign workers and their families.

Key Points

- Low-income countries are unlikely to create sufficient number of jobs to absorb into productive work the millions of additional young workers who will enter their labor markets in the upcoming decades.

- Income gains from labor mobility from low productivity to high productivity places overwhelmingly exceed gains from other programs aimed at poverty reduction.

- Labor mobility has been an effective tool allowing people in low income countries around the world to escape poverty.

Introduction

Many people around the world are trapped in poverty as a result of their country of birth. More than half of variability in income globally is explained by their country of birth; meaning that individual effort or luck can explain only a small portion of the global distribution in income.[i] This implies that, mostly, “there are not poor people but only people in poor places.”[ii] Labor mobility allows people to leave their homes to work abroad, and thus secure better life for themselves as well their loved ones. However, when addressing labor mobility, politicians, researchers as well as general public often focus primarily on the impacts on sending and receiving countries. While it is certainly important to consider and assess impacts of labor mobility on the involved nations, their economies and citizens, it is necessary to also analyze the impact on those who are affected by labor mobility the most directly – foreign workers and their families themselves. Despite a number of risks and challenges, labor mobility has proved to be, at the margin, the most effective tool to reduce poverty among people in low-income countries.

Why Do Workers Go Abroad?

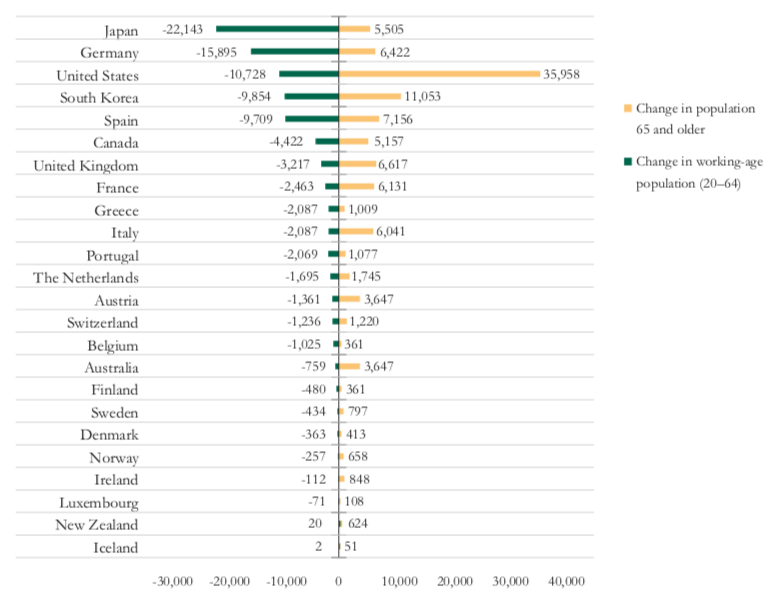

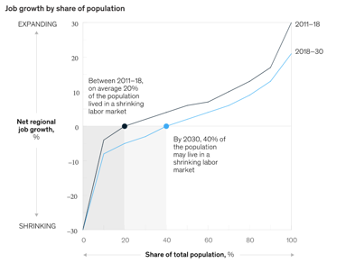

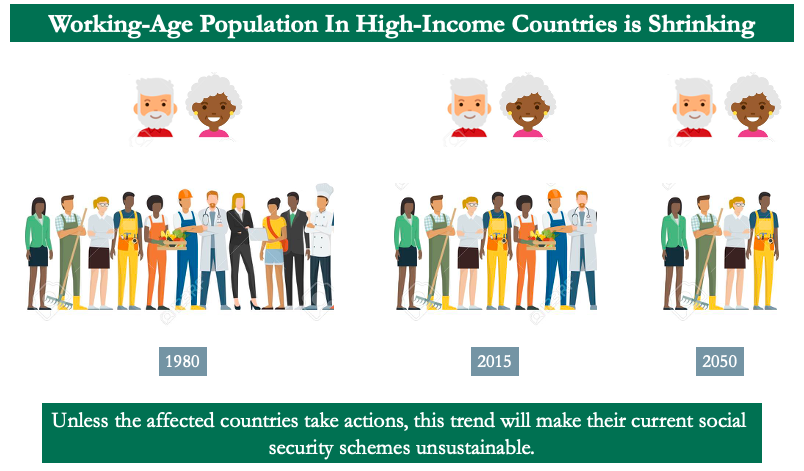

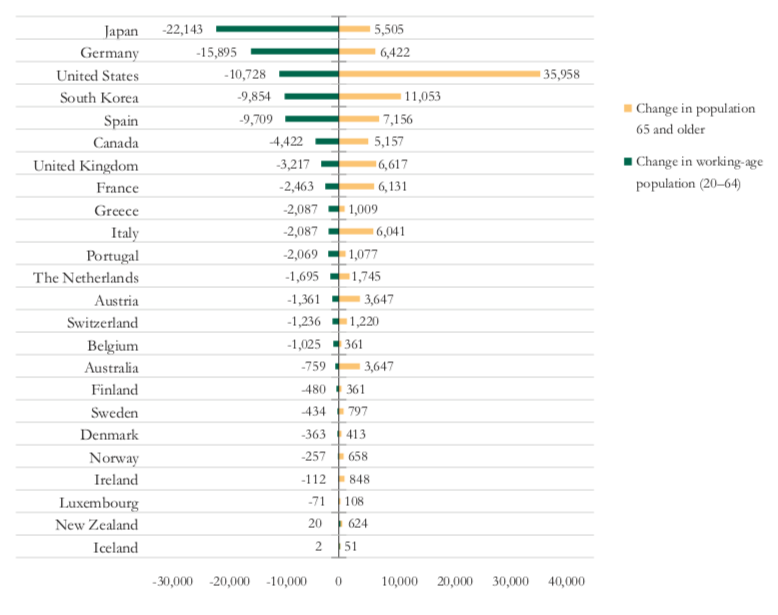

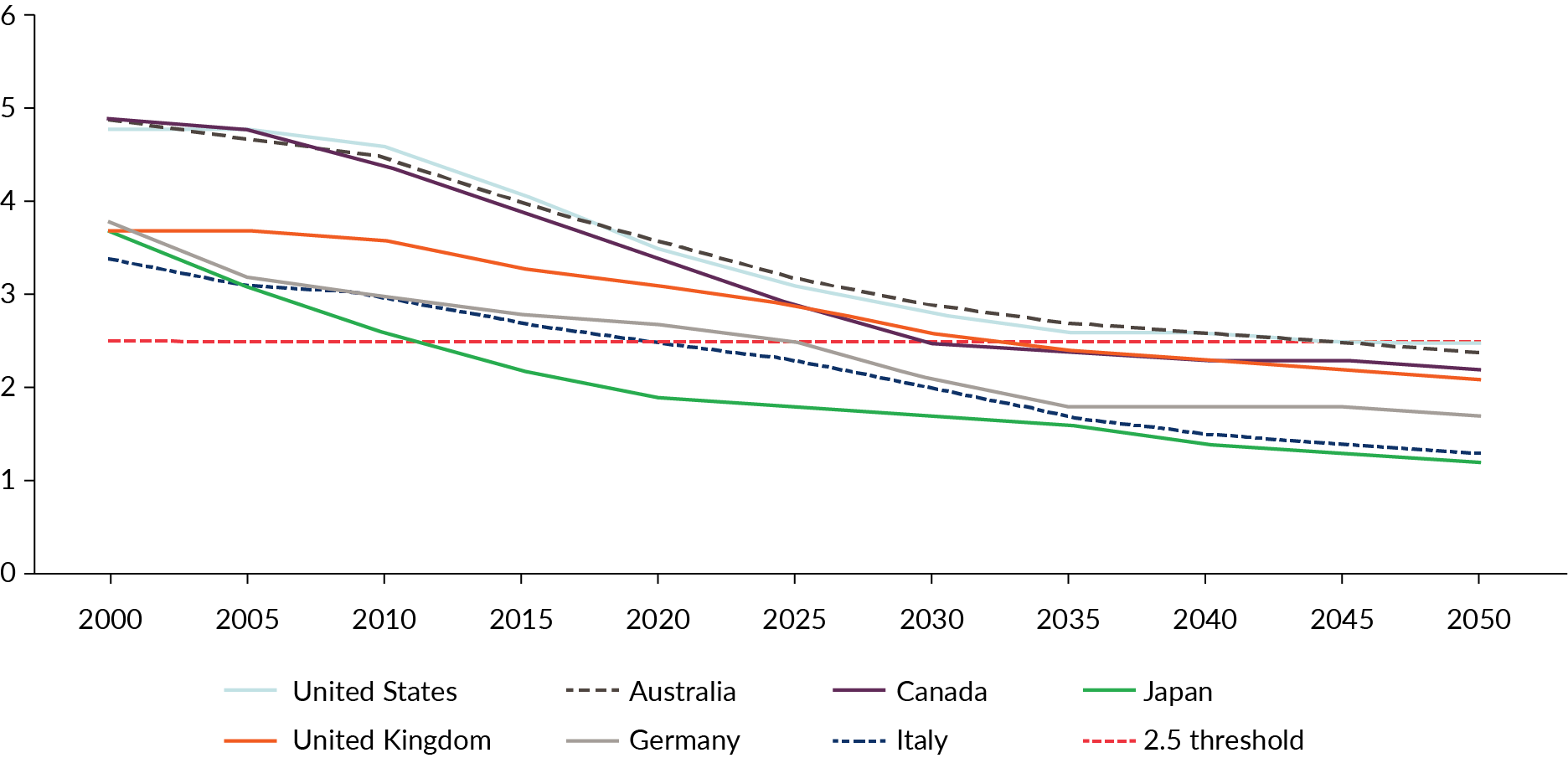

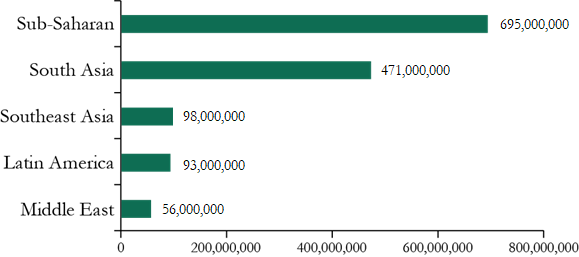

Foreign workers’ desire to leave stems primarily from the desire to find better employment opportunities. There are already millions of workers in low-income nations, who are trapped in low-productivity places, and this trend unlikely to change. By 2050, low-income countries’ working-age populations are estimated to grow by millions, and even hundreds of millions in case of sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia (Figure 1). Most of these additional workers are young, between 19 and 30 years old, which presents a number of concerns. According to research, lack of productive employment at the beginning of a young people’s careers negatively impacts social cohesion, physical[iii] and mental health,[iv] as well as long term employment and income outcomes.[v] Youth bulges are also associated with increased risks of violent conflict[vi] that are particularly aggravated by youth unemployment.

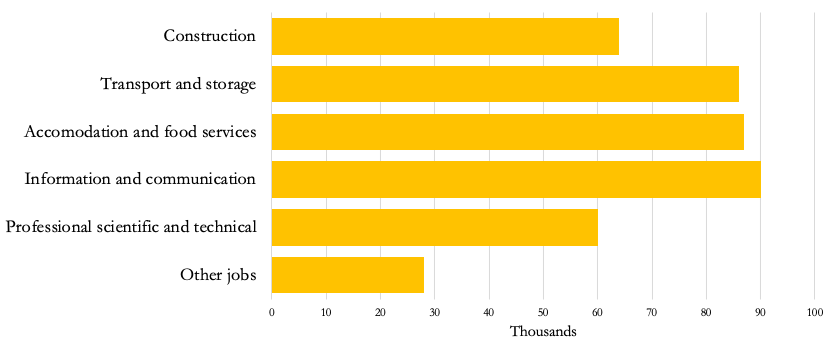

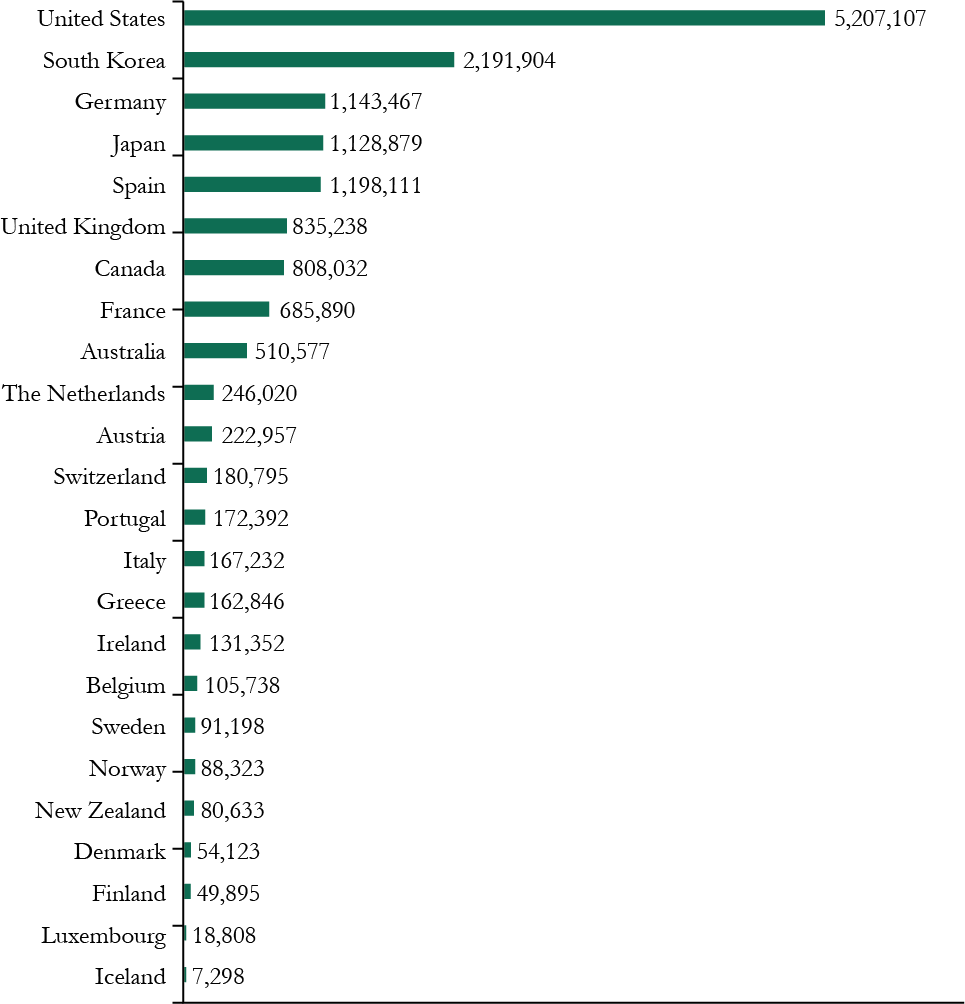

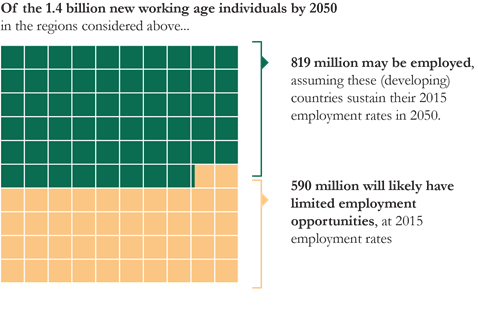

At the countries’ current employment levels, research shows that up to half of the new workers would remain unemployed (Figure 2)[vii]. In other words, low-income countries are unlikely to create sufficient number of jobs to absorb the additional labor market entrants.

Figure 1. Change in working-age population (20–64) between 2015 and 2050[viii]

Source: UN DESA, Population Division (2015)

Figure 2. At current employment rates, only 819 million of the new working age people would enter employment[1]

Sources: UN DESA, Population Division (2015); ILO (2019).

The size and demographic composition of the nations’ future labor force is expected to fuel migration outflow as many of the new workers will want to move and follow the opportunity[ix], since working abroad is the single most effective step towards improving their own well-being and in many cases prosperity of entire families as we discuss below.

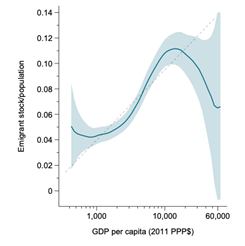

Moreover, even if the nations managed to introduce reforms aimed at reduction of unemployment, it would not automatically guarantee lower level of emigration. A recent study revealed that while policy intervention to decrease unemployment, no matter whether among the relatively poor or the relatively rich populations, could lead to decline of emigration in the short term, the same would not be true in the long term. Higher income not only fails to prevent peoples’ decision to leave, it actually allows individuals in those poor nations to unlock more opportunities, and thus empowers them to go abroad. In fact, research shows that people in low-income countries, who are actively preparing to emigrate, have on average 30 percent higher incomes than those who do not actively prepare to leave.[x]

Therefore, in addition to reforms to boost peoples’ incomes in their home countries, politicians should also put more emphasis on establishment of well-regulated labor mobility policies, which are clearly more beneficial to foreign workers and their families.

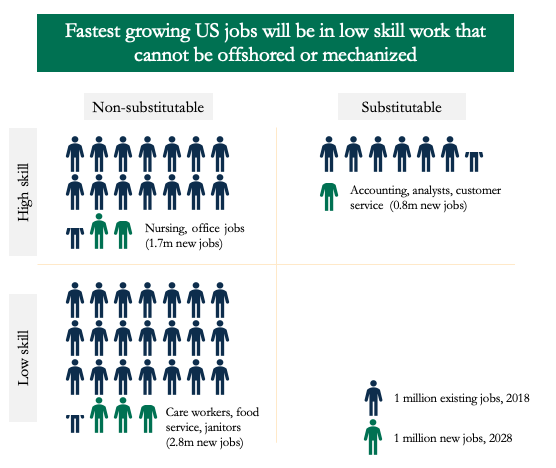

Foreign Workers’ Income Gains

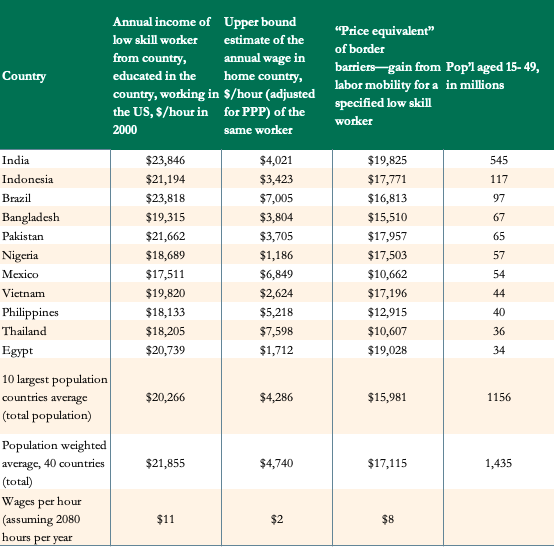

One of the main reasons why people decide to move for work, often across the entire world, is the opportunity to seek more lucrative jobs,[xi] and thus ensure better future for themselves and their families. And the differences have been quite considerable. When workers find employment abroad, estimates show they can increase their income as much as 6 to 15 times for their wage in their home country.[xii] Additionally, workers from low-income countries hold about 7 percent of jobs in high-income countries, and as Jason DeParle cited economist Lant Pritchett in his book A Good Provider Is One Who Leaves, “every increase of a percentage point would leave them more than $100 billion richer.”[xiii] As for a more concrete example, a separate study on alleviating global poverty recently showed that income gains from allowing an additional low skill worker to move to the USA from various countries are between $10,000 and $20,000 a year (Table 1).

Table 1. The income gains from allowing an additional low skill worker to move to the USA from various countries

Source: Pritchett, L. (2018, March). Alleviating Global Poverty: Labor Mobility, Direct … Retrieved October 25, 2020, from https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/alleviating-global-poverty-labor-mobility-direct-assistance-and-economic-growth.pdf

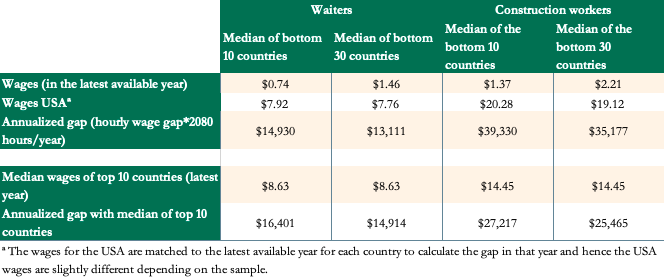

Similarly, in a separate example focused on specific occupations, the study showed a nearly $15,000 annualized gap between the real (PPP) adjusted wages of waiters in the top 10 wage countries when compared the bottom 30 countries. For occupations in construction sector, the difference is even bigger – almost $25,500 (Table 2).[xiv] Additionally, it is likely that the wage gains from labor mobility as a whole are even larger, as the total consists for a mix of skill levels; and higher skill levels typically equal larger wage gains. However, in this note we focus particularly on wage gains of individuals with lower skill levels, since the growing young populations in sending countries are very low skilled in comparison to richer nations.[xv]

Table 2. Earnings (PPP) for identical low to medium skill occupations are different between poor and rich countries

Source: Pritchett, L. (2018, March). Alleviating Global Poverty: Labor Mobility, Direct … Retrieved October 25, 2020, from https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/alleviating-global-poverty-labor-mobility-direct-assistance-and-economic-growth.pdf

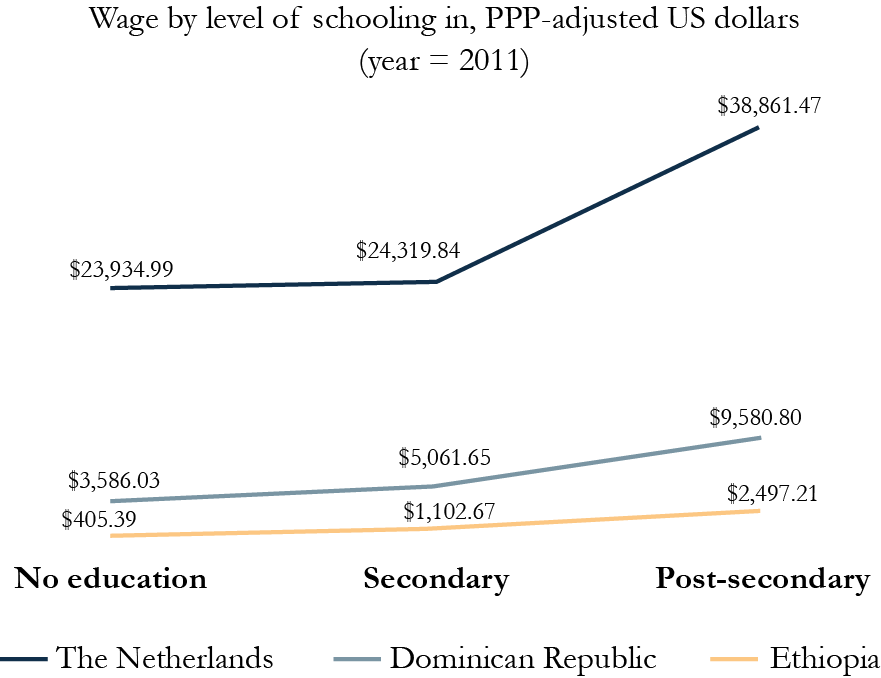

As the studies mentioned above suggest, labor mobility is clearly a powerful tool for poverty alleviation, as it provides even low-skilled foreign workers with an opportunity to obtain massive income gains if they get hired in a high-income country. For example, in 2011, an Ethiopian with very little to no schooling would, on average, earn PPP$405 annually. However, this same individual could earn PPP$24,000 in the Netherlands. It is also important to note that in many countries, the potential income gain from mobility exceeds the gain from investing in schooling. For an Ethiopian, potential return on investment in schooling (if he or she decided to pursue postsecondary schooling rather than remain without any schooling) is quite negligible in comparison to the return on moving to a country like the Netherlands. This is given by the fact that, on average and at the margin, an Ethiopian can increase his or her income by a factor of 6 by pursuing postsecondary schooling in Ethiopia, while the same individual with no schooling can earn 10 times the Ethiopian’s wage in the Netherlands (Figure 3).[xvi]

Figure 3. In many countries, the potential income gain from mobility exceeds the gain from investing in schooling

Source: Smith, Rebekah, and Farah Hani. “Labor Mobility Partnerships: Expanding Opportunity with a Globally Mobile Workforce.” Center For Global Development, June 26, 2020. https://www.cgdev.org/publication/labor-mobility-partnerships-expanding-opportunity-globally-mobile-workforce.

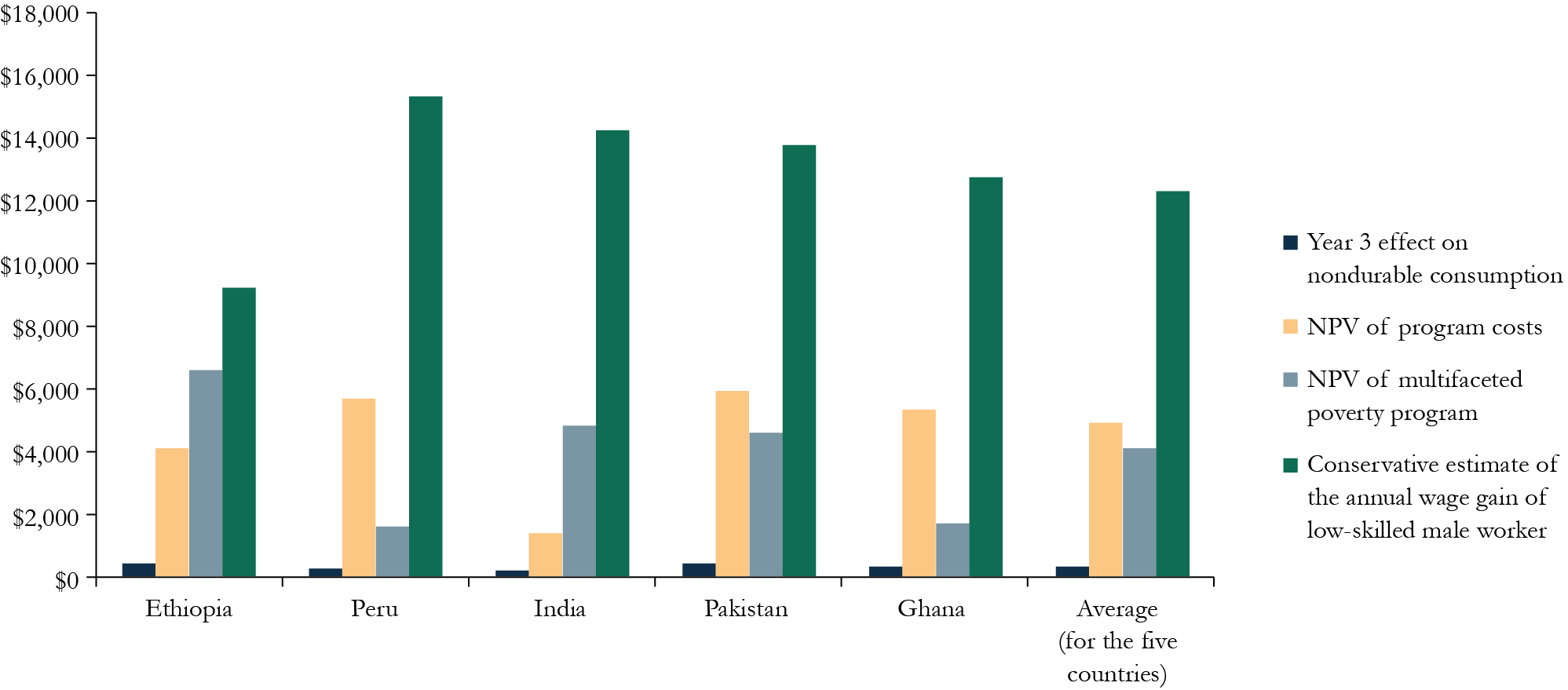

With such large income gains, labor mobility has been clearly a powerful tool allowing people in low income countries around the world to escape poverty. Research shows that implementation of effective policies, allowing for well-regulated mobile labor force, is far more effective than any other poverty reduction tool.[xvii] For instance, the Ultra-poor Graduation Program, has been touted as a gold-standard poverty reduction program that has been adopted by several nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and widely celebrated for its demonstrated impact based on a cross-national rigorous study. On average across the countries studied, the program invests a net present value (NPV) of $4,545 over the course of two years[2] and generates on average $344 gain in non-durables consumption gains in the third year. However, as the Figure 4 below shows, the less than 10 percent average rate of return on the program. Even on the most optimistic assumptions about the duration of the program gains, the lifetime gain from this program is much smaller than the additional wages from one year working in the USA.

Figure 4. Income gains from labor mobility dwarf the less than 10 percent average rate of return on the Ultra-poor Graduation Program—a gold-standard poverty reduction program.

Source: Smith, Rebekah, and Farah Hani. “Labor Mobility Partnerships: Expanding Opportunity with a Globally Mobile Workforce.” Center For Global Development, June 26, 2020. https://www.cgdev.org/publication/labor-mobility-partnerships-expanding-opportunity-globally-mobile-workforce.

Further, labor mobility achieves these powerful gains in poverty reduction without an upfront investment from governments or donors, whereas programs like the anti-poverty interventions mentioned above require someone to put up money. This means that the “least you can do for the world’s poor is better than the best you can do;” that is, simply not prohibiting workers and employers from engaging in mutually beneficial cross-border transactions is much more powerful than the best programs development aid can finance.[xviii]

The considerable increases in income gains stemming from labor mobility have been a strong incentive for individuals in low-income countries to seek jobs abroad. Labor mobility represents a much more effective poverty-reduction tool than other programs. And last but not least, besides helping the foreign workers themselves, the income gains also represent a great relief to their families back in their countries of origin. As Jason DeParle said during a LaMP virtual event, migration is in fact an anti-poverty program.[xix]

Remittances Received by Foreign Workers’ Families

Every year, many foreign workers send money back home to their families. These transfers, generally known as remittances, serve as a powerful tool uplifting well-being of families around the world, and especially in low-income countries. In many cases, remittances have been responsible for lifting the receiving families out of poverty. Specifically, a study conducted among seventy-one low-income nations revealed that a 10-percent gain in remittances reduces the number of people living in poverty by 3.5 percent.[xx] In Philippines, for instance, a 10-percent income gain from remittances lowered the poverty rate among receiving households by 2.8 percentage points.[xxi] For families in Afghanistan, remittances averaged $1,680 annually, which accounts for more than half of their income, and the households typically use them for basic needs.[xxii]

Since remittances flow directly into households who are able to use them to bolster their consumption, education and health spending,[xxiii] they have proven to positively impact nutrition standards,[xxiv] healthcare,[xxv] and children’s school attendance[xxvi] as well as reducing child mortality.[xxvii] In general, evidence suggests that consumption, health and education are the three main areas for which families in low income countries typically use their remittances. However, remittances are often touted also as a potential source of investment financing. Even though this trend has been less proven, there have certainly been places where it occurred. Scattered data suggests that families in low-income countries use resources accumulated while working abroad also for investment in building a house, starting a business, and financing education.[xxviii]

Overall, remittances inflows are counter-cyclical in sending countries, stabilizing income and insulating families of migrants from adverse economic shocks.[xxix] Estimates show that total global remittances reached $689 billion in 2018, out of which $529 billion went to “developing” or low-income countries.[xxx] In India, for example, remittances received from migrants in Gulf alone rival private investment the country gets from the entire world.[xxxi]

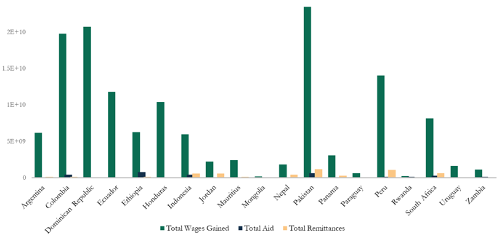

However, while incredibly powerful, it is important to keep in mind that remittances capture only a small portion of the foreign workers’ income gain. Adhikari and Stellitano[xxxii] estimated the total wage gains from 19 non-OECD countries residing in 8 OECD countries. Figure 5 below reflects these total gains compared to total remittances and foreign aid for each of the non-OECD countries, showing that the total wage gains are clearly way larger than either remittances or foreign aid.

Figure 5: Wage gains are vastly larger than either remittances or foreign aid[3]

Source: Adhikari, S., & Stellitano, N. (2015). Migration as an Instrument for International Development. Retrieved October 26, 2020, from http://adhikarisamik.github.io/

Upskilling and Skill Gains Upon Return

Besides income gains and remittances that can be expressed in financial terms, workers employed overseas also accumulate skills which they then bring back upon their return home. Specifically, workers gain skills abroad due various training they gain either on the job itself, or through the company as well as other external mandated or voluntary courses. Upon their return, the workers can then capitalize on these acquired skills to secure a job that requires higher skills and provides better salary than they would have if they had not migrated.[xxxiii] For example, research showed that returnees in Brazil, Chile, and Costa Rica have been overrepresented in highly skilled occupations and underrepresented in least-skilled trades.[xxxiv]

Additionally, the new abilities may make the workers more attractive to potential employers, or in combination with potentially accumulated savings possibly allow them to open their own new businesses and train people at home.[xxxv] Evidence shows that when Indian- and Chinese-born software engineers, returned after the U.S. stock market bubble in late 1990’s, also known as the U.S. dotcom bubble, they had transferred institutional and technical knowledge and techniques to their home countries.[xxxvi] Also, when the Greek sovereign debt crisis spurred a return of large numbers of Albanians, more than half of the returnees took jobs as skilled workers in the industries, in which they were employed in Greece, while many other engaged in entrepreneurship using techniques they had learned abroad, creating jobs for themselves as well as non-migrants.[xxxvii]

Overall, migration opportunities increase earning potential for the workers, who in turn increase the return to skilling in their sectors. The new skills allow the returned workers to get better jobs, open new businesses, while teaching others what they had learned abroad. studies show, migrants return home wealthier, multilingual, more educated than people in their communities, with more work experience than those who have never lived abroad, and larger social networks and new technical abilities. Therefore, their homecoming typically results in a “brain gain” that benefit not only themselves and their families, but also their community and often even their country of origin as a whole.[xxxviii]

Challenges Faced by Foreign Workers

While labor mobility clearly represents the most effective tool to help individuals and their families to escape poverty, there are also some challenges that must be taken into account while creating and implementing labor mobility policies. The current labor mobility systems have been struggling with defects such as fraud, extortionary costs, worker abuse, and illegality, that adversely affect foreign workers. One of the best examples of these dynamics have been the nations of Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), which have helped to millions of families to escape poverty through labor mobility flows, but also saw frequent cases of worker abuse and fraud.

It is well documented that many foreign workers in a variety of existing migration systems experienced practices such as wage withholding, forced overtime, workplace health and safety violations, passport withholding, and a range of other forms of abuse. Some of the most disturbing examples include the 2022 Doha World Cup, with repeat reported cases of migrants going for months without pay,[xxxix] being forced to work overtime, living in sub-standard conditions, and even dying.[xl] Nepal has recently experienced an alarming trend of kidney disease in its young population, primarily among migrant workers who do long hours of physical labor in the desert, become dehydrated, and use painkillers at higher rates, all of which combine to make them vulnerable to renal failure.[xli] Canada has had famous cases of temporary foreign workers being subjected to unsanitary housing, wage withholding, and recruitment fraud.[xlii] Additionally, women migrants, who often work in the domestic sphere where there is little or no oversight, are uniquely vulnerable, resulting in excessive working hours,[xliii] physical and sexual abuse,[xliv] and again in the most severe cases death.[xlv] Moreover, workers, especially those working at low-skill jobs, are less likely to feel “comfortable acknowledging that they have rights and exercising them,” as pointed out by William Gois, the Regional Coordinator of the Migrant Forum in Asia, during a LaMP’s virtual event.[xlvi]

The COVID-19 era has further stressed vulnerabilities of foreign workers in many countries. Migrants have been at higher risk of contracting the virus due to inadequate health care, worse economic conditions, and overcrowded living conditions. For example, 40 percent of Singapore’s COVID-19 cases in in mid-April were low-skilled foreign workers, resulting from their overcrowded and unsafe dormitory accommodations.[xlvii] At the same time, a majority of individuals infected by the virus in the Gulf are migrants.[xlviii] The International Monetary Fund expects the Middle Eastern and North African economies to fall by 5.7 percent in 2020, which will lead to a surge in unemployment, wage theft and unpaid work as businesses close their doors, spike in detentions and deportations due to visa expirations and increasing need for food handouts. In Lebanon, 250,000 foreign workers have been already hit by such hardship, being left abandoned and unpaid.[xlix] Overall, the pandemic further stressed the flaws of existing labor migration systems, pointing out the multitude of abusive practices and behaviors.

Moreover, labor mobility flows are frequently characterized by extortionary high costs that amount to as much as nine months to more than a year’s salary abroad. For example, a recent study revealed that workers from Latin America and Asia paid intermediaries between $3,000 and $27,000 to secure visas to the US,[l] while the World Bank reports that South Asian workers regularly pay $3,000 to $4,000 for jobs in Gulf Cooperation Council countries.[li] These costs are primarily paid towards recruitment agency fees; in Bangladesh, intermediary fees account for more than 75 percent of the overall migration costs.[lii] Therefore, many workers arrive abroad in debt which puts them into very sensitive situations, as they must maintain employment to be able to pay down their debts regardless of the potential abusiveness of their employers. A recent study on foreign workers in Singapore revealed that indebted workers “sometimes choose to endure harsh and/or unsafe working conditions rather than risk the [premature] repatriation” from raising concerns with their employers.[liii] It has been clear that the excessively high costs caused by the lack of transparency within the current market structure undermine the development potential of labor mobility.

Further, in many migration systems, work visas, and especially temporary work visas, are tied to a specific employer. This means that the workers cannot leave their employers without losing their visa status. For example, in the U.S., employer-tied visas have been directly linked to potential for worker abuse, as workers on employer-restricted visas filed over 100 complains to the Federal Court for wage and hour deception between 1990 and 2017 compared to eight from workers on unrestricted visas.[liv]

And last but not least, psychological studies show that migrant workers have been increasingly prone to serious, psychotic, anxiety, and post-traumatic disorders caused by a number of socio-environmental factors, such as loss of social status, discrimination, and separations from the family. The verbal or physical abuse that foreign workers often face when employed in dangerous, unhealthy jobs leads to a variety of disorders, including depression, anxiety, alcohol or substance abuse, and poor sleep quality, causing low life conditions.[lv] And yet, foreign workers are willing to undergo all the hardship and arrange their lives around family separation, rather than returning to the in many cases extreme poverty in their home countries. In other words, while we may see migration as tragedy, for many foreign workers it is an opportunity, as DeParle put it.[lvi]

Still, all the bad outcomes of labor mobility work to create a powerful political coalition against it, with irregularity fueling the anti-immigrant right wing and concerns around worker abuse building opposition from the left wing. However, it is important to point out that these outcomes are not inherent to labor mobility, but rather a result of poorly constructed systems and incentives. Therefore, workers from low-income countries need well-regulated efficient labor mobility systems, which will allow them and their families to escape poverty while protecting them from risks and eliminating challenges that come with the decision to move abroad. Moreover, as Joe Martinez of CIERTO suggested, a part of these systems should be also an ecosystem of actors creating oversight of governments and safety for the workers.[lvii]

Conclusion

Despite the unquestionable benefits labor mobility brings to foreign workers and their families, sending as well as receiving countries tend to implement inefficient policies that further restrict labor mobility. The stringent measures have been typically based on the thinking that without restrictions on migration, migrants from poor countries could transmit low productivity to rich countries.[lviii] However, models show that a 3-percent increase in the OECD labor force through relaxed restrictions on labor mobility would produce $150 billion[4] in global welfare gains, accounting for gains to the movers, gains and losses in host countries, as well as gains and losses in sending countries. According to 2006 estimates from the World Bank, a 3-percent increase in OECD labor force over a decade-long period would result in $674 billion in global welfare gains, which is 5 times total development assistance.[lix] These vast gains, unrealized as a result of policies restricting labor mobility, are what economist Michael Clemens’ famously refers to as ‘trillion dollar bills on the sidewalk.’[lx] Additionally, according to a separate research, gains from lowering barriers to emigration appear to largely exceed gains from further reductions in barriers to goods trade or capital flows.[lxi]

So, what does this mean for the existing as well as future labor mobility policies? A recent study aimed at making the case for efficiency-enhancing migration barriers[5] showed that while dynamically efficient policy would not mean any open borders measures, it would certainly include relaxations of current restrictions. In other words, the new efficiency case for some migration restrictions seems to be a case against the stringency of these existing restrictions.[lxii]

As an example, New Zealand is one of the first countries that have recognized the potential of seasonal worker programs to become part of international development policy. Its Recognized Seasonal Employer program is one of the most prominent systems designed through this perspective, and its results revealed increased per capita incomes, expenditure, savings, and subjective well-being among the participating migrants.[lxiii] At the same time, displacement of the native-born workers has remained low. Data also showed that foreign workers, who come to New Zealand through the program, seem to be more productive than local labor and their productivity rises as they return for more seasons.[lxiv]

Labor mobility clearly holds vastly more promise for reducing poverty than anything else on the development agenda.[lxv] It allows workers from low-income countries to go abroad, and thus support themselves as well as their families and relatives back home – a practice that eventually leads to overall poverty reduction. Therefore, the existing labor mobility systems with overly strict restrictions hurt not only the foreign workers themselves but also the involved sending and receiving countries overall. At the same time, the current policies often fail to prevent abuse of foreign workers, allowing for dynamics that leave physical as well psychological harm on the affected individuals.

It is necessary for the governments of sending as well as receiving countries, employing sectors and other actors in the mobility industry to cooperate with foreign workers and organizations that represent them. Together these actors can establish common policies and standards allowing for efficient and safe mobility of foreign workers, resulting in overall reduction of poverty on global scale.

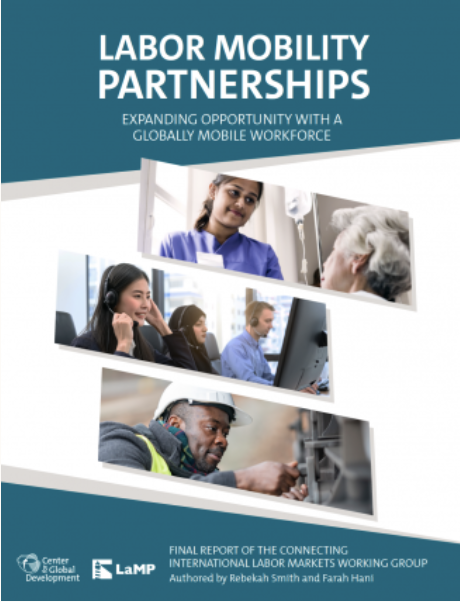

About LaMP

[1] Figure 2 shows how many of the total number of new working age people would likely be able to find employment versus those who would remain unemployed by 2050, if the current employment rates were maintained. Under this scenario, an estimated 590 million of the 1.4 billion new working age people would have limited access to employment opportunities. Yet even this is an optimistic forecast, as the current projections of job growth would not be sufficient to absorb even the remaining 819 million.

[2] Measured across the five countries where the program has the biggest impact.

[3] Adhikari and Stellitano assessed a set of 19 non-OECD and 8 OECD countries. Wage data was provided by Claudio Montenegro of the World Bank. Bilateral migration data by educate and gender from 1980-2000 was drawn from the IAB Brain Drain Data. Bilateral remittance data for 2010 was drawn from the World Bank. Bilateral aid data for 2010 came from AidData.

[4] In 1997 prices.

[5] The study considered three main parameters – transmission, which is defined as “the degree to which origin-country total factor productivity is embodied in migrants”; assimilation defined as “the degree to which migrants’ productivity determinants become like natives’ over time in the host country”; and congestion, which is “the degree to which transmission and assimilation change at higher migrant stocks.”

[i] Milanovic, B. (2015, January 2). Global Inequality Of Opportunity: How Much Of Our Income Is Determined By Where We Live? Retrieved October 25, 2020, from https://stonecenter.gc.cuny.edu/files/2015/05/milanovic-global-inequality-of-opportunity-how-much-of-our-income-is-determined-by-where-we-live-2015.pdf

[ii] Pritchett, L., & Hani, F. (2020, July 30). The Economics of International Wage Differentials and Migration. Retrieved October 26, 2020, from https://oxfordre.com/economics/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190625979.001.0001/acrefore-9780190625979-e-353

[iii] Sanford, M. N., & Mullen, P. E. (2011, January 19). Health Consequences of Youth Unemployment. Retrieved October 25, 2020, from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00048678509158851?journalCode=ianp20

[iv] McQuaid, R. (2017, February 18). Youth unemployment produces multiple scarring effects. Retrieved October 25, 2020, from https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2017/02/18/youth-unemployment-scarring-effects/

[v] Mroz, T. A., & Savage, T. H. (2003, July). The Long-Term Effects Of Youth Unemployment. Retrieved October 25, 2020, from https://economics.yale.edu/sites/default/files/files/Workshops-Seminars/Labor-Public/mroz-030912.pdf

[vi] Urdal, H. (2006, September). A Clash of Generations? Youth Bulges and Political Violence. Retrieved October 25, 2020, from https://www.jstor.org/stable/4092795?seq=1

[vii] Smith, Rebekah, and Farah Hani. “Labor Mobility Partnerships: Expanding Opportunity with a Globally Mobile Workforce.” Center For Global Development, June 26, 2020. https://www.cgdev.org/publication/labor-mobility-partnerships-expanding-opportunity-globally-mobile-workforce.

[viii] Ibid.

[ix] Ibid.

[x] Clemens, M. M., & Mendola, M. (2020, August). Migration from Developing Countries: Selection, Income Elasticity, and Simpson’s Paradox. Retrieved October 25, 2020, from https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/migration-developing-countries-selection-income-elasticity-and-simpsons-paradox.pdf

[xi] World Migration report 2018 (Rep.). (2017). Retrieved October 25, 2020, from International Organization for Migration website: https://www.iom.int/sites/default/files/country/docs/china/r5_world_migration_report_2018_en.pdf

[xii] Michael A. Clemens & Claudio E. Montenegro & Lant Pritchett, 2019. “The Place Premium: Bounding the Price Equivalent of Migration Barriers,” The Review of Economics and Statistics, MIT Press, vol. 101(2), pages 201-213, May.

[xiii] DeParle, J. (2019). A Good Provider Is One Who Leaves: One Family And Migration In The 21st Century. Viking.

[xiv] Pritchett, L. (2018, March). Alleviating Global Poverty: Labor Mobility, Direct … Retrieved October 25, 2020, from https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/alleviating-global-poverty-labor-mobility-direct-assistance-and-economic-growth.pdf

[xv] Smith, Rebekah, and Farah Hani. “Labor Mobility Partnerships: Expanding Opportunity with a Globally Mobile Workforce.” Center For Global Development, June 26, 2020. https://www.cgdev.org/publication/labor-mobility-partnerships-expanding-opportunity-globally-mobile-workforce.

[xvi] Ibid.

[xvii] Pritchett, L. (2018, March). Alleviating Global Poverty: Labor Mobility, Direct … Retrieved October 25, 2020, from https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/alleviating-global-poverty-labor-mobility-direct-assistance-and-economic-growth.pdf

[xviii] Pritchett, L. (2016, October 25). The Least You Can Do for Global Poverty Is Better than the Best You Can Do. Retrieved October 25, 2020, from https://www.cgdev.org/blog/least-you-can-do-global-poverty-better-best-you-can-do

[xix] Workers on the Move: Labor Mobility As a Powerful Tool for Alleviating Poverty. (2020, October 22). Retrieved October 25, 2020, from https://lampforum.org/what-we-do/research-and-advocacy/events/1434-2/

[xx] DeParle, J. (2019). A Good Provider Is One Who Leaves: One Family And Migration In The 21st Century. Viking.

[xxi] Yang and Martinez

[xxii] https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/afghanistan/publication/labor-migration-can-help-boost-afghanistans-growth

[xxiii] Ahmed, Junaid and Mughal, Mazhar, How Do Migrant Remittances Affect Household Consumption Patterns? (January 30, 2015). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2558094 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2558094

[xxiv] Antón, José-Ignacio. “The Impact of Remittances on Nutritional Status of Children in Ecuador.” The International Migration Review. 44(2). Summer 2010. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25740850?seq=1

[xxv] Amuedo-Dorantes, Catalina and Pozo, Susan. “New Evidence on the Role of Remittances on Health Care Expenditures by Mexican Households.” IZA Discussion Paper No. 4617. December 2009. http://ftp.iza.org/dp4617.pdf

[xxvi] Acosta, P. “Labor Supply, School Attendance, and Remittances from International Migration: The Case of El Salvador.” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 3903. 2006. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

[xxvii] Chauvet, Lisa, Gubert, Flore & Mesplé-Somps, Sandrine. “Aid, Remittances, Medical Brain Drain and Child Mortality: Evidence Using Inter and Intra-Country Data.” The Journal of Development Studies, 49:6. 2013. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00220388.2012.742508?journalCode=fjds20

[xxviii] Wahba, Jackline. “Return migration and economic development.” Chapters, in: Robert E.B. Lucas (ed.),International Handbook on Migration and Economic Development, chapter 12. 2014. Edward Elgar Publishing.

[xxix] De, Supriyo et al. “Remittances over the Business Cycle: Theory and Evidence. Global Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development. World Bank Group. March 2016. https://www.knomad.org/sites/default/files/2017-07/KNOMAD%20WP%2011%20Remittances%20over%20the%20Business%20Cycle.pdf

[xxx] Remittances: KNOMAD. (n.d.). Retrieved October 25, 2020, from https://www.knomad.org/data/remittances

[xxxi] DeParle, J. (2019). A Good Provider Is One Who Leaves: One Family And Migration In The 21st Century. Viking.

[xxxii] Adhikari, S., & Stellitano, N. (2015). Migration as an Instrument for International Development. Retrieved October 26, 2020, from http://adhikarisamik.github.io/

[xxxiii] Debnath, P. (2016, November). Leveraging Return Migration for Development: The Role of Countries of Origin (Rep.). Retrieved October 25, 2020, from KNOMAD website: https://www.knomad.org/sites/default/files/2017-04/WP%20Leveraging%20Return%20Migration%20for%20Development%20-%20The%20Role%20of%20Countries%20of%20Origin.pdf

[xxxiv] Dumont, J.-C., and G. Spielvogel. “Return Migration: A New Perspective.” In International Migration Outlook, Part III. 2008. Paris: OECD Publishing.

[xxxv] Best, E. (2017, May 3). How U.S. Employment Affects Returning Migrants. Retrieved October 25, 2020, from https://psmag.com/news/when-migrant-workers-return-home-24836

[xxxvi] Giordano, A., and G. Terranova. 2012. “The Indian Policy of Skilled Migration: Brain Return versus Diaspora Benefits.” Journal of Global Policy and Governance 1 (1): 17–28.

[xxxvii] Hausmann, Ricardo and Nedelkoska, Ljubica. “Welcome Home in a Crisis: Effects of Return Migration on the Non-migrants’ Wages and Employment.” European Economic Review. 2017.

[xxxviii] Waddell, B. (2019, July 16). When migrants go home, they bring back money, skills and ideas that can change a country. Retrieved October 25, 2020, from https://theconversation.com/when-migrants-go-home-they-bring-back-money-skills-and-ideas-that-can-change-a-country-118093

[xxxix] Reality Check: Migrant Workers’ Rights in Qatar. (2019). Retrieved October 25, 2020, from https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/campaigns/2019/02/reality-check-migrant-workers-rights-with-four-years-to-qatar-2022-world-cup/

[xl] Slater, M. (2019, June 04). Qatar 2022 World Cup organisers address ‘high number’ of worker deaths. Retrieved October 25, 2020, from https://www.independent.co.uk/sport/football/world-cup/qatar-2022-world-cup-deaths-workers-report-a8943096.html

[xli] Rai, O. (2017, April). A mysterious rash of kidney failures: Nation: Nepali Times. Retrieved October 25, 2020, from http://archive.nepalitimes.com/article/Nepali-Times-Buzz/A-mysterious-rash-of-kidney-failures,3639

[xlii] Tomlinson, K. (2019, April 08). Threats, crippling debt and lives lost: Human trafficking leaves foreign workers suffering in silence. Retrieved October 25, 2020, from https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-threats-crippling-debt-and-lives-lost-human-trafficking-leaves/

[xliii] Cousins, S. (2018, August 29). Will Migrant Domestic Workers in the Gulf Ever Be Safe From Abuse? Retrieved October 25, 2020, from https://www.newsdeeply.com/womensadvancement/articles/2018/08/29/will-migrant-domestic-workers-in-the-gulf-ever-be-safe-from-abuse

[xliv] Za’za’, B. (2017, February 08). Housewife jailed for torturing maid. Retrieved October 25, 2020, from https://gulfnews.com/news/uae/courts/housewife-jailed-for-torturing-maid-1.1975182

[xlv] Wang, A. B., & Murphy, B. (2018, April 03). How a maid found dead in a freezer set off a diplomatic clash between the Philippines and Kuwait. Retrieved October 25, 2020, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2018/04/03/how-a-maid-found-dead-in-a-freezer-set-off-a-diplomatic-clash-between-the-philippines-and-kuwait/?noredirect=on

[xlvi] Workers on the Move: Labor Mobility As a Powerful Tool for Alleviating Poverty. (2020, October 22). Retrieved October 25, 2020, from https://lampforum.org/what-we-do/research-and-advocacy/events/1434-2/

[xlvii] (Gee 2020).

[xlviii] Karasapan, O. (2020, September 17). Pandemic highlights the vulnerability of migrant workers in the Middle East. Retrieved October 25, 2020, from https://www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2020/09/17/pandemic-highlights-the-vulnerability-of-migrant-workers-in-the-middle-east/

[xlix] Ibid.

[l] http://www.verite.org/sites/default/files/images/HELP%20WANTED_A%20Verite%CC%81%20Report_Mig

[li] Migrant recruitment costs. (2020, June 9). Retrieved October 25, 2020, from https://migrationdataportal.org/themes/migrant-recruitment-costs

[lii] Das, N., De Janvry, A., Mahmood, S., & Sadoulet, E. (2018, April 16). Migration As a Risky Enterprise: A Diagnostic For Bangladesh. Retrieved October 26, 2020, from https://are.berkeley.edu/esadoulet/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Migration-as-a-risky-enterprise.pdf

[liii] Baey, G., & Yeoh, B. S. (2015, February). Migration and Precarious Work: Negotiating Debt, Employment, and Livelihood Strategies Amongst Bangladeshi Migrant Men Working in Singapore’s Construction Industry. Retrieved October 26, 2020, from http://www.migratingoutofpoverty.org/files/file.php?name=wp26-baey-yeoh-2015-migration-and-precarious-work.pdf&site=354

[liv] Gibbons, Eric M., Allie Greenman, Peter Norlander, & Todd Sørensen, “Monopsony Power and Guest Worker Programs,” IZA Institute of Labor Economics, IZA DP No. 12096 (January 2019).

[lv] Mucci, N., Traversini, V., & Giorgi, G. (2019, December). Migrant Workers and Psychological Health: A Systematic Review. Retrieved October 25, 2020, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/338118715_Migrant_Workers_and_Psychological_Health_A_Systematic_Review#:~:text=Migrant%20workers%20show%20an%20increase,and%20separations%20from%20the%20family

[lvi] Workers on the Move: Labor Mobility As a Powerful Tool for Alleviating Poverty. (2020, October 22). Retrieved October 25, 2020, from https://lampforum.org/what-we-do/research-and-advocacy/events/1434-2/

[lvii] Ibid.

[lviii] Clemens, M. A., & Pritchett, L. (2016, February). The New Economic Case for Migration Restrictions: An Assessment (Rep.). Retrieved October 25, 2020, from http://ftp.iza.org/dp9730.pdf

[lix] Pritchett, L. (2018, March). Alleviating Global Poverty: Labor Mobility, Direct … Retrieved October 25, 2020, from https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/alleviating-global-poverty-labor-mobility-direct-assistance-and-economic-growth.pdf

[lx] Clemens, Michael, A. 2011. “Economics and Emigration: Trillion-Dollar Bills on the Sidewalk?” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 25 (3): 83-106.

[lxi] Ibid.

[lxii] Clemens, M. A., & Pritchett, L. (2016, February). The New Economic Case for Migration Restrictions: An Assessment (Rep.). Retrieved October 25, 2020, from http://ftp.iza.org/dp9730.pdf

[lxiii] Gibson, J., & McKenzie, D. (2014, January). Development through Seasonal Worker Programs: The Case of New Zealand’s RSE Program. Retrieved October 26, 2020, from https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/18356/WPS6762.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

[lxiv] Ibid.

[lxv] Pritchett, L. (2018, March). Alleviating Global Poverty: Labor Mobility, Direct … Retrieved October 25, 2020, from https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/alleviating-global-poverty-labor-mobility-direct-assistance-and-economic-growth.pdf