Key Points

- Sending and receiving countries lay out their interests when negotiating their domestic- as well as international-level policies. Despite best intents, many migration systems fail to achieve these goals in practice.

- Migration policies and international agreements are crucial tools through which countries establish the terms of migration, but to be successfully implemented in practice, they must be underpinned by an effective and efficient implementing infrastructure.

- Where policy change is not sufficient, we can improve outcomes in migration systems by strengthening the technical design of these structural elements.

Introduction

For those seeking to improve migration systems, the focus often falls primarily on policymakers and the changes they can bring to migration policies and regulations. This is often a steep uphill battle since the policy environment is in many cases strongly resistant to change.

However, changing policies is not the only way to strengthen migration systems. In fact, focusing solely on policy change underestimates the importance of implementing infrastructure and employment services behind these policies in determining the impacts of migration systems. This suggests that where policy change is far off, we can improve outcomes in migration systems by strengthening the technical design of these structural elements.

In this policy note, we argue that how legal frameworks interact with the other core pillars of a migration system is key to the effectiveness of migration policies. In other words, while migration policies and international agreements are crucial tools through which countries establish the terms of migration, they must be underpinned by an effective and efficient implementing infrastructure and a quality mobility industry delivering employment and support services to ensure the policy is fully implemented in practice.

Framework

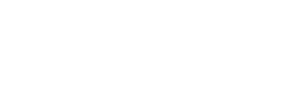

Migration systems consist of three key elements: (1) the legal framework establishing the rights and conditions under which a worker from one country may be employed in another; (2) infrastructure implementing this framework; and (3) services through which workers find and secure jobs and are supported throughout the migration cycle.[1] Underpinning these three elements are monitoring and risk mitigations to ensure transparency and adequate protections for workers, and sustainable financing mechanisms to align the incentives of all actors. In this policy note, we use this as a descriptive framework to identify the fundamental core of migration systems; that is, these are the elements necessary for basic functioning of existing systems allowing workers to move into jobs in a well-managed way. Other functions (skill certifications, remittance transfers, etc.) may be added to significantly improve the functions of a system; however, for purposes of this policy note we focus exclusively the core elements required to function.

Figure 1: The Elements of a Labor Mobility System

Source: Rebekah Smith & Farah Hani, Labor Mobility Partnerships: Expanding Opportunity with a Globally Mobile Workforce, Center for Global Development (June 26, 2020), https://www.cgdev.org/publication/labor-mobility-partnerships-expanding-opportunity-globally-mobile-workforce

While sending and receiving countries are motivated by different interests when negotiating their policies – domestically and at international level – their objectives generally fall within three categories: (1) economic interests, in addressing labor market shortages in receiving countries and surplus labor in sending countries; (2) political interests, primarily in reinforcing cooperation to stem irregular migration; and (3) development objectives, seeking to maximize the development potential of labor flows from developing countries or to mitigate risks of migration.[2]

Despite best intents, many migration systems have not achieved these goals in practice. For example, administrative data from the Philippines (“one of the world’s most prolific promoters of labor migration and signers of bilateral labor agreements”) found no evidence that signing bilateral labor agreements (BLAs) resulted in increased out-migration of Filipinos through these corridors or remittance inflows to the Philippines.[3] Existing memoranda of understanding (MoUs) were not found to be successful in meeting objectives of improving recruitment systems (in the case of GCC countries and Malaysia) or reducing irregular migration (in the case of Thailand’s MoUs with Cambodia, Lao PDR, and Myanmar).[4] However, signing BLAs is associated with an increase in the stock of migrants in host countries, but it is not clear that the BLAs are responsible for this increase.[5]

For the purpose of this policy note, we define an effective system as one in which (1) workers regularly and predictably move through the channel and (2) workers’ rights are protected through clearly defined and fully implemented terms of migration. In order to regularly move workers through the channel, a system must be (1) flexible and demand-driven, focusing primarily on opening labor market access to address labor shortages and meet employers’ demand in select sectors;[6] 2) accessible to a broad range of employers and workers and cost-effective, reducing the total cost of migration to the extent reasonable. To ensure migrant rights are protected through clearly defined and fully implemented terms of migration, the system needs to be (3) transparent, so all involved actors understand their rights, responsibilities, and processes, and (4) integrated across borders through partnerships among parties on both sending and receiving side rather than a single overseeing authority.

The overall effectiveness of a labor mobility program is influenced by the structural elements both of legal frameworks and of the implementing infrastructure and employment services supporting it. Structural elements tied to these objectives include costs of migration and distribution of costs, processes for selecting workers and terms of employment, mechanisms for arbitration of disputes, and regulations for seeing to the protection of workers. This suggests that the effectiveness of mobility systems can be improved by strengthening the technical design of these structural elements.

In the following section, we explore how disconnects between the legal framework and the other core elements undermine their effectiveness.

Disconnects Between Elements of Labor Mobility Systems Undermining Effectiveness: Regular Movement through the Corridor

When the legal framework is not paired with robust implementing infrastructure and employment services, it is unlikely to facilitate regular movement through the corridor. The labor market access created by open migration channels may not be used in practice if there are not systems to connect employers with vacancies in the destination to jobseekers in the origin. The absence of active employment services may explain why visa access offered by a visa channel or a bilateral agreement alone has not been found to be effective in meeting the goals of facilitating migration flows.[7] For example, the governments of Afghanistan and Qatar signed an MoU in 2008 which was expected to allow 25,000 Afghan workers to move into jobs in Qatar; however, as of 2018 only a handful of workers ever found employment in Qatar via this agreement, due to the weak capacity of Afghan recruitment systems.[8] Similarly Japan has struggled to recruit workers at sufficient scale through the new Specified Skills Visa, though there is little information on specific barriers to its implementation.[9] [10] [11]

Additionally, when the legal framework is not paired with an effective and efficient implementing infrastructure, workers are less likely to move through it regularly. Ineffective infrastructure results in higher time and cost burdens for prospective migrants; if this time and cost burden significantly exceeds that associated with irregular migration, irregular migration can become the more attractive option. In implementing the MoU on regularizing migrants between Cambodia and Thailand. Workers present irregularly in Thailand were provided an identity card and a work permit for a total of 5500 baht, high relative to an average monthly wage of 1500 baht. The efficacy of the MOU has been very limited (with roughly 30% take up), as the cost of regular migration is much higher than the cost of irregular migration in this corridor.[12] Similarly, the insufficient implementing infrastructure in Ethiopia has resulted in a lengthy and redundant migration process – the process migration is long and complex with a number of redundancies and unnecessary steps.[13] each with delays of up to 2-3 months.

The lengthy process places a very real time and cost burden on the worker, incentivizing them to pay an agent to take on this burden or even to migrate irregularly to avoid the process altogether. In the Ethiopian context, members of the poorest families often opt for irregular migration as it is perceived as cheaper than going through regular channels.[14] Significant documentation requirements and the lengthy deployment process can also lead migrants to seek out recruitment agencies that can expedite deployment by falsifying documents; a 2007 study of labor migrants in three Indonesian provinces found that more than 40% of documents were falsified.[15] Redundancies in Myanmar’s labor sending system, with many manual stages processed and approved by multiple agencies, are shown to contribute to the prevalence of irregular migration while not meaningfully improving the quality of the migration experience for workers or employers.[16]

Case Study: Korea’s Employment Permit System

In 2004 South Korea introduced the Employment Permit System (EPS), in an effort to prevent irregular migration and answer labor scarcity in small and medium industries engaged in construction, manufacturing and services.[17] The EPS is managed entirely on a government-to-government (G2G) basis, underpinned by MoUs between Korea and the Ministry of Labor in each country of origin.[18] This means that the entire process, including worker recruitment and intermediation services, are handled directly by government agencies on both sides rather than any private sector actors, distinguishing the EPS from many other migration systems.[19] As of 2018, 16 origin countries[20] had partnered with Korea through the EPS, and more than 540,000 workers had moved into temporary jobs through the program since its inception.

The current G2G approach taken under the EPS is a response to problems under its predecessor, the Industrial Trainee System (ITS). The first challenge was high migration costs due to unregulated private recruitment activities, which in turn causes workers to overstay their visas to recoup the high migration costs. The second challenge was rights issues and exploitation as workers under the ITS did not have protection under Korea’s labor regulations.[21] It is worth noting that these are two of the three key problems identified in the previous section as resulting from a disconnect between the legal framework and implementing infrastructures. Under the G2G approach, the entire process is managed by the Korean government in co-ordination with the sending countries’ governments. These responsibilities include delivering a mandatory Korean language test during the pre-decision stage, workers’ identification and recruitment, provision of job-matching services and worker protection and counseling, and assistance with returns and settlement.[22]

The Indonesia-Korea MoU can provide an example of how this works in practice. The Director General of Placement and Development of Indonesian Overseas Workers (PDIOW) is identified in the MoU as responsible for recruiting, selecting and sending the workers, with the language test administered by the Korean Ministry of Labor. PDIOW is to prepare a roster of eligible jobseekers, who are then selected by employers in Korea. The Department of Manpower and Transmigration in India oversees delivery of predeparture orientation by a public agency. Public entities on both sides cooperate for the repatriation of migrants who are staying illegally in Korea, and if the percentage of Indonesian migrants staying irregularly in Korea will exceeds a certain percentage the visa allocation for Indonesia workers will subsequently be reduced. The MOU includes an annex which goes into more details on the hiring procedures.[23]

The EPS’s approach to BLA implementation has been a success by many metrics. By publicizing detailed costs of participating in the EPS and thus discouraging intermediaries from overcharging, the EPS was able to reduce costs paid by workers from USD 3,700 in its predecessor to less than USD 1,000, making it one of the lowest-cost destinations for workers in the world.[24] By reducing the upfront costs to the workers as well as strengthening bilateral cooperation between Korea and participating sending countries, the EPS has also managed to reduce the total number of migrant workers who overstayed their mandated time decreased from about 50% under the ITS period to less than 10% in 2014 under the EPS.[25] The EPS has also improved efficiency though robust interoperable ICT systems between ministries, and strengthened worker protections by including migrant workers in Korean labor laws and providing support services.

However, this approach to implementation also has its share of challenges and may not be appropriate for some contexts. This model depends heavily on the capacity of government institutions on both sides of the corridor. The EPS was built on the foundation of the Ministry of Employment and Labor’s infrastructure for intermediation and job matching as well as worker counseling, which allowed the Government of Korea to tap into economies of scale by expanding existing services to migrant workers, and further depends on the robust ICT infrastructure mentioned above. This model would struggle in the absence of an existing strong public employment service (PES), as is the case in many sending and receiving countries. Even with a strong PES, the success rates of the job matching process in the EPS are low. A large share of jobs posted through the EPS are not successfully matched with migrant workers and a significant share of those workers who are successfully matched with employers change jobs within a year.[26] The number of EPS workers entering Korea in the past few years was below the overall quota, only about 50% of the posted vacancies for EPS workers were successfully filled and over 60% of workers change jobs.

Disconnects Between Elements of Labor Mobility Systems Undermining Effectiveness: Integrated, Transparent Processes

Perhaps the most common impacts of a disconnect between the legal framework and implementing infrastructure are those relating to the terms of migration, particularly as relates to the cost of migration, rights, and employment conditions. Migration policies frequently include stipulations around each of these issues; however, without addressing the underlying dynamics causing them related to incentive structures in employment services and gaps in implementing systems, they are unlikely to deliver on the terms of the policies in practice. Here again, we focus on technical aspects of the design of mobility systems, though systemic power imbalances cannot be ignored are a core driver of these outcomes.

An example of this is extortionately high costs and fraud associated with recruitment and employment services. Labor mobility flows are frequently characterized by costs amounting to as much as nine months’ to more than a year’s salary abroad.A report by Verité, a US-based NGO, found that workers from Latin America and Asia paid intermediaries between USD 3,000 and 27,000 to secure visas to the US,[27] while the World Bank reports that South Asian workers regularly pay USD 3,000 to 4,000 for jobs in GCC countries.[28] These payments are made upfront, forcing workers to either sell off assets or take on debt with extremely high interest rates. Worse still, workers often arrive in the receiving country to find that the job is not as expected, or the pay not what they were promised. Verité reported that 43% of the Nepali workers they interviewed signed a different contract upon arrival in the receiving country with different terms to those they agreed to before migrating, and 36% never signed any contract. A 2019 GFEMS study, mentioned above, found that 61% of Bangladeshi male migrants surveyed never saw a contract, 44% reported deception by middlemen, and 24% reported deception by employers.[29] In the worst cases, migrant workers arrive to find there is no job.[30]

These bad outcomes of migration systems are driven by mis-aligned incentives and a lack of transparency and accountability throughout the process. First, the system of upfront payments creates no incentive for recruitment agencies to find quality employment for workers. Recruitment agencies receive payment either way, while sourcing and vetting quality vacancies requires greater effort (and expenditure) on their part. Second, there is a lack of transparency and accountability throughout the migration process. These are inherently cross-border operations, with different actors and different regulations on each side of the border, and no single entity responsible for ensuring the quality of the process from start to finish. BLAs are intended to address this by creating a consistent regulation across borders and aligning enforcement efforts; however, in practice this has been difficult to achieve without cross-border partnerships on implementation infrastructure and oversight.

Migration systems face similar challenges with enforcing stipulations around employment conditions. This has been particularly evident during the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, millions of workers were repatriated during the pandemic without being paid the wages they were due.[31] These workers have no avenue for redress as the issue falls within the jurisdiction of the host country, which they cannot access having been repatriated to their home country, leading to calls from civil society organizations for a cross-border mechanism to evaluate and assess claims of non-payment.[32]

Conclusion

The effectiveness of migration systems towards their goals of facilitating and increasing share of regular movement and enforcing quality standards through integrated, transparent processes hinges on how they interact with support implementing infrastructure and employment services. As the examples in this policy note showed, disconnects between the legal framework and the other core elements undermine the effectiveness of policies and international agreements and result in many of the problems we see in mobility systems today. In some cases, the absence of implementing infrastructure and employment services has prevented movement of workers though the corridor, and in others the existence of a low-quality mobility industry has undermined enforcement of the terms of migration particularly relating to employment fees, labor standards, etc.). This suggests that where policy change is far off, we can improve outcomes in migration systems by strengthening the technical design of these structural elements.