A care system under strain

The UK’s adult social care system is under intense pressure, and in recent months it has become a proxy for a wider debate about migration. As part of the government’s efforts to reduce net migration, the UK closed the door to new international recruitment of care workers in July 2025, citing concerns about exploitation and poor practice by providers, alongside a stated shift towards boosting domestic recruitment and retention.

While politically clear, the decision has had real consequences for the care industry and wider UK economy. Vacancy rates remain significantly above whole-economy norms – around three times higher – and the sector’s inability to recruit overseas workers is compounding long-standing staffing gaps. The number of posts filled by British nationals continues to fall, and projections indicate the sector will need around 470,000 additional workers by 2040, making the recruitment gap increasingly acute.

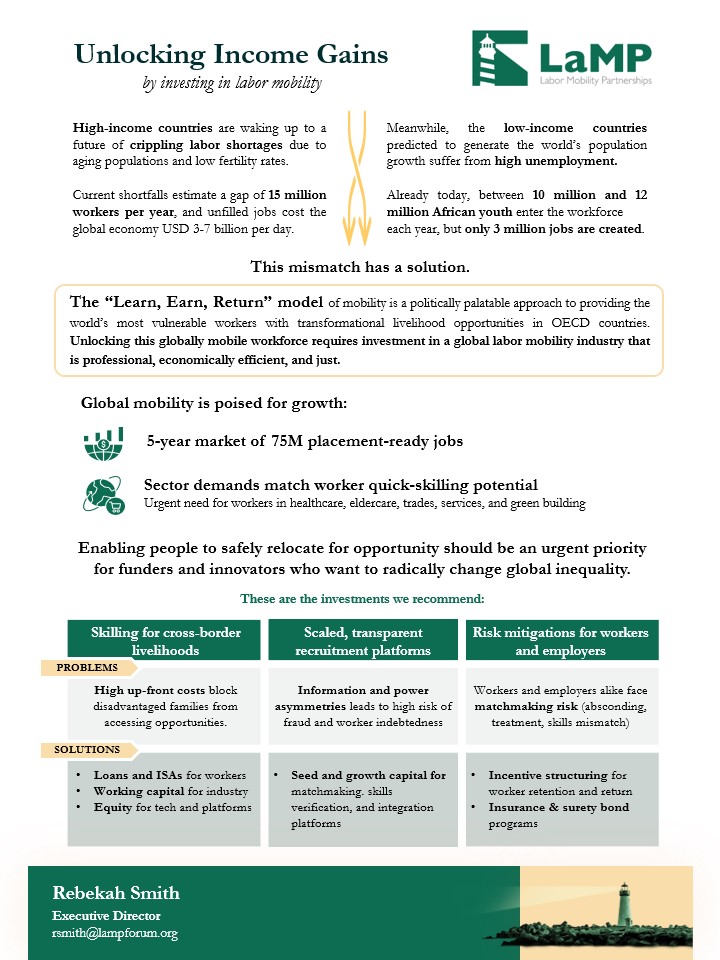

Through a two-wave consultation from April 2025 to December 2025, LaMP engaged more than 100 stakeholders across government, public and private sector organisations, and the care system, including those representing migrant workers. A consistent picture emerged: recent policy changes have exposed a sponsorship system that lacks flexibility to manage disruption, with around 28,000 displaced care workers struggling to transition quickly into new roles. The problem is worsened by a fragmented redeployment and matching system that is difficult to navigate. Set against high turnover and rising demand, these barriers have heightened concerns about the future availability and mobility of the care workforce.

National responses to displaced care workers

In England, responses have focused largely on matching workers to vacancies through regional partnership models backed by targeted government funding while Scotland has introduced comparable public funding for employers. Partnerships, such as in the North-East, have shown promising results in coordinating employers and displaced workers and bridging opportunities between England and Scotland. However, their reliance on time-limited government funding raises questions about long-term sustainability.

Differing funding and delivery arrangements across nations create divergence, and uneven service quality has resulted in a “postcode lottery” for workers and employers. Even where displaced workers are connected to vacancies, conversion into employment remains low, reflecting systemic challenges including inconsistent skills recognition, slow sponsorship processes, and uneven regional support.

The intention behind these responses is sound: help qualified workers already in the UK move into new employment while safeguarding their status. Under the current visa system, sponsored care workers can legally change employers only if they secure a new sponsor and receive a new Certificate of Sponsorship within 60 days of leaving their role. In practice, delays in UKVI processes create disruption, with new Certificates of Sponsorship taking eight to more than twenty weeks to issue, leaving many unable to move roles before their status becomes precarious. Ad-hoc matching practices – though well intended – further increase inconsistency in the system.

Alongside these efforts, platforms like Borderless and Lifted have emerged to connect workers and employers and improve vacancy visibility, showing the potential of digital and partnership-based approaches. While affective, they operate within the same structural constraints: limited skills recognition, visa rigidity, and low employer confidence.

Why matching alone can only go so far

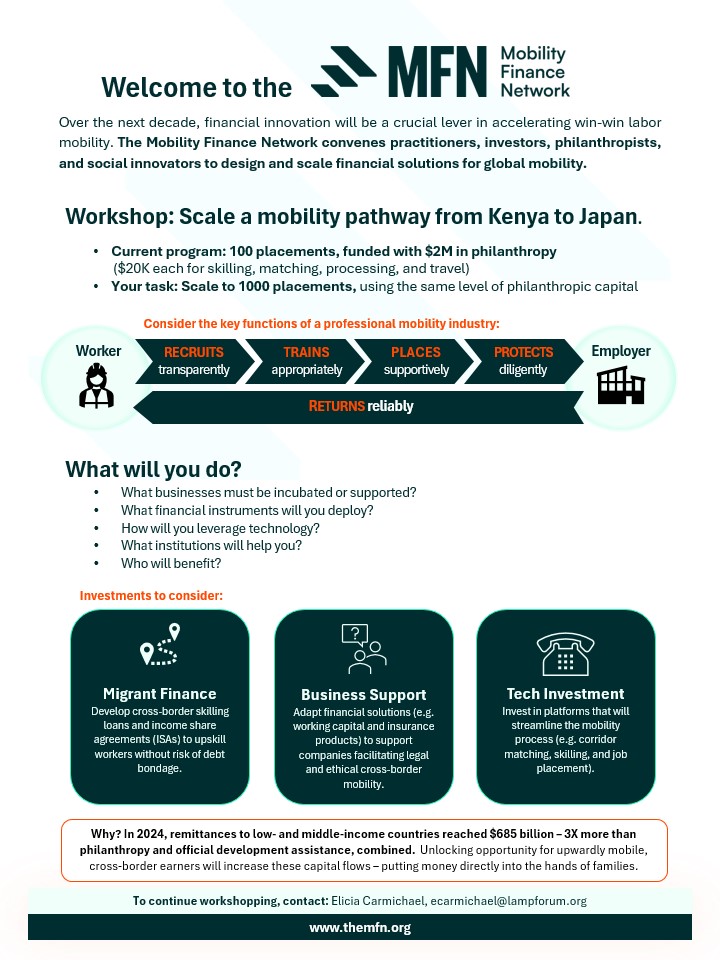

Matching workers is largely a short-term band-aid, helping a small number of people. Re-employment is slow, employer confidence fragile, and many workers never reach the point of being considered appointable. The problem is not just stakeholders’ coordination or vacancies’ visibility. It is skills.

The UK is dealing with the consequences of a migration route used as a workforce solution, without the infrastructure needed to make that workforce functional. This is compounded by a structural misalignment: migration policy is set at a UK-wide level, while social care is devolved. Workers are admitted through a single national visa route into systems that are delivered, regulated and supported very differently across nations.

These challenges stem from how the care worker visa route operated, allowing entry without fully accounting for the complexity of the social care system or role demands. Many workers arrived with limited prior experience, low or even non-existent qualifications, and no clear way to prove their competences. There was no robust mechanism for recognising prior learning, verifying skills, or creating a portable record of competence.

Skilling as the missing link

The UK government has introduced measures to strengthen domestic training and progression such as the Learning and Development Support Scheme for the adult social care workforce. While this provides an important boost to domestic skills development, without shared infrastructure for skills recognition and portability, foreign workers still struggle to evidence their skills, and even with relevant experience, there is often no recognised way to prove it. Employers find training and experience hard to verify, confidence in foreign-obtained credentials remains low, and risk feels high following recent sponsorship misuses. Visa rules further limit flexibility, requiring full-time sponsorship with little scope for part-time roles or extended probation periods to test suitability.

In a high-turnover sector, this combination of risk and rigidity stalls recruitment, leaving visa portability difficult to realise in practice. Matching alone helps only those who already fit the system, leaving the majority constrained by unrecognised skills and credentials.

If the aim is to support displaced workers and sustain the workforce, skilling must sit at the centre of the response. Workers with recognised training, clearer language competence, and verifiable evidence of their skill, become more employable and more mobile. At the same time, skilling restores employer confidence, creates a clearer signal of capability, reduces perceived risk, and makes recruitment decisions easier and faster.

Building a resilient system for the future

Tools already exist: Targeted short-term training aligned to care roles, recognition of prior learning, language and workplace readiness support, and emerging digital or AI-enabled systems for skills verification. What is missing is a strategic decision to prioritise them. Redirecting funding from subsidising recruitment or matching towards skilling would shift the system from short-sight mitigation to long-term value, aligning more closely with the government’s stated aim of building a more skilled workforce – benefiting international and domestic workers. This has been acknowledged in Skills for Care’s Adult Social Care Workforce Strategy, which explores approaches to address workforce skills shortages.

While UK policy has brought these challenges into sharp focus, they are not unique. Similar pressures are emerging across high-income countries facing long-term care shortages. Initiatives focused on workforce viability and skills portability, such as the Global Apprenticeship Network, demonstrate the need for durable, internationally informed solutions. Over time, this approach helps clarify what skills the sector needs, what standards employers trust, and the infrastructure required if international recruitment were to reopen in the future.

Regional partnerships and other national support can still play a role, but their value lies in local knowledge and tailored skilling programs, not in subsidising matching or recruitment costs. Combined with infrastructure such as a national register of skills and credentials, they could help create a system that understands the workforce it is trying to support and responds accordingly.

Right now there is a risk of focusing on the wrong lever. Matching is visible and politically attractive, but it does not address the root problem. What’s needed is a deliberate shift towards building skills, credibility and trust across the system.