Key Points

- Because there is no explicit general definition of a high-skilled versus low-skilled worker, such categorizations are often arbitrary and sometimes even contradictory.

- To increase the overall complexity of their economies, and thus boost growth, high-income countries need a much broader variety of abilities than the traditional low- and high-skill dichotomy, which is solely based on a worker’s level of schooling.

- Rather than using the arbitrary education-focused definitions of skill levels, labor mobility schemes should focus on the capabilities needed by employers hiring sectors, including a worker’s ability to learn and develop new skills during their employment in the host country.

- Implementing better quality labor pathways for foreign-born workers with a broad variety of skills would add to the overall economic growth of the receiving countries while also assisting native-born workers with their own realization and potential career advancement.

Introduction

An economy is a complex system, under which each worker’s skills and specialization has its own value that complements the capabilities of others—a process that ultimately leads to increased overall economic growth. As Hausmann found, complexity is in fact at the center of countries’ economic growth and development.[i] The argument may be easier to understand using the following metaphor. A simple economy makes bread, which only requires a few ingredients, including a great deal of flour, but no eggs. A more sophisticated economy produces both bread and cake, the latter of which requires flour and eggs. And an even more sophisticated economy might produce a variety of breads, pastries, and cakes, which requires the specialized skills of a chef, who can create new recipes using existing and new ingredients. Note that each of the economies still need flour to produce their goods. In terms of migration, high-income countries strive to attract more entrepreneurs, information technology (IT), and other experts with advanced degrees to continue expanding the range and depth of sophistication of their economies. However, the “recipes” for modern economies still require “flour”—in other words, there is still a need for caregivers for the young and the old—as well as cleaners, roofers, painters, and retail workers; and many employers in high-income countries struggle to fill these and other jobs due to increasing labor scarcities.

All workers—whether native- or foreign-born—offer a wide range of skills and abilities, from social and cultural skills to those learned from previous experiences or even at school, which advances and increases the complexity of an economy. And yet, when it comes to foreign-born workers, many existing labor mobility systems in high-income countries traditionally use a dichotomy based on educational attainment, simply splitting the workers into two groups: high–skilled or low-skilled. So-called high-skilled workers typically have at least a four-year degree and work as IT experts, medical doctors, scientists, or other professionals that require a postsecondary degree; while so-called low-skilled workers have less schooling than a bachelor’s degree and work, for example, as agricultural and construction laborers, welders, and caregivers.

In fact, the capabilities of foreign-born workers represent a kind of “skills mix,” consisting of educational attainment and knowledge of another language, skills acquired through previous or current employment, and interpersonal and other social skills. In other words, a foreign-born worker brings an entire package of abilities, which could possibly help both companies in employing sectors of high-income countries as well as workers and their families in their countries of origin if a worker decides to return. However, for a country to bring in a variety of workers with a broad range of skills, it needs flexible mobility pathways that allow for the safe entry of workers with skill sets that correspond to the needs of the host country’s economic sectors. Moreover, data show that, when combined with other enforcement measures, implementation of additional quality labor mobility programs for workers with diverse skill sets could help reduce irregular migration channels.[ii]

Nevertheless, high-income countries are not particularly willing to admit additional foreign-born workers who possess a broader array of skills. High-income countries have frequently demonstrated the political appetite for developing pathways to admitting highly skilled foreign-born workers to work in sectors, such as IT, medicine, and science. Since professions in these fields have clear and established training and certifications systems, it is easier for high-income countries to label them high-skilled. However, other occupations that require extensive training are not likewise recognized. Employers and workers in construction, care work, tourism, and similar fields are therefore often at a disadvantage due to the failure of countries to develop adequate mobility pathways that recognize the skills and training that is required for these sectors. Although the inclination toward highly skilled workers stems from a variety of factors, data show that many foreign-born workers traditionally labeled as low-skilled due to their lower level of schooling in fact play important roles in the lives of native-born workers and help increase overall productivity. Receiving countries may find that it is more beneficial to base labor mobility schemes on sector needs rather than on the educational level of workers.

Implementing additional quality mobility pathways for foreign-born workers with a broader variety of skills would increase economic complexity for both the receiving high-income countries and the sending countries because workers returning home can continue to use and teach others their skills. Research shows that such new abilities may make workers more attractive to potential employers or, in combination with accumulated savings, potentially allow them to open businesses of their own and train people in their native countries.[iii] Moreover, upon their return, workers can capitalize on their acquired skills to secure jobs that require higher skill levels and that provide better salaries than those they could have obtained prior to their migration.[iv] For example, a study on returnees to Brazil, Chile, and Costa Rica reveal that such workers are overrepresented in highly skilled occupations and underrepresented in least-skill trades.[v] A separate analysis by Natasha Iskander, focused on Mexican construction workers in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and Raleigh-Durham, North Carolina, revealed that “as immigrants move their knowledge from one labor market context to another, they change its form and composition.” The change is so radical that “it is more accurate to say that it is transformed, rather than merely transferred.”[vi] Increasing and improving mobility systems for workers with all kinds of skills and abilities, not only for those with a high level of education, could be a powerful tool in the development strategies of high-income countries because the resulting increase of economic complexity also impacts countries of origin.

The Traditional Dichotomy of Foreign-Born Workers’ Skills

Workers are typically considered skilled if they have reached a specific level of education, if they have obtained specific certifications, or if their expected pay levels or wages are above a certain threshold. However, the exact definition of skilled varies by country as each sets its own eligibility criteria and types of visas.[vii] Moreover, when discussing labor mobility, politicians, economists, and other experts tend to use rhetoric that splits workers into two groups—high-skilled and low-skilled.[1] High-skilled workers typically have at least a bachelor’s degree and engage in positions such as IT experts, medical doctors, and scientists. Low-skilled workers usually have less schooling than a four-year degree and tend to be engaged as agricultural or construction laborers, welders, caregivers, and cooks. This dichotomy has been used as an actual basis for the migration systems of high-income countries. The United States, for example, defines highly skilled foreign-born workers as those who have earned at least a bachelor’s degree;[viii] all other workers are considered low-skilled. In Europe, countries tend to establish their migration systems along the two skill levels as well. Spain, for example, defines high-skilled workers as those with at least a graduate degree.[ix] Japan issues its highly skilled professional visas to applicants seeking jobs in academia, engineering, and business management, which typically require doctoral or master’s degrees.[x]

Even when countries use other characteristics to divide foreign-born workers into groups, they still tend to end up with similar groups of “high” and “low.” Canada, for example, changed its system in 2014 to define its two categories of workers based on their wages rather than on their skills. The country’s temporary foreign-born worker program has been divided into two categories: high-wage workers, including positions offering wages at or above the established provincial or territorial median wage, and low-wage workers, with pay below the median wage level. In fact, however, the occupations in these two categories basically cover the same positions as the previous system of high- and low-skill, which divided foreign-born workers based on if they had obtained a postsecondary education or formal certification.[xi] Although this may be a less value-laden way to classify foreign-born workers, it still serves to give preference to one group over another.

This dichotomy toward foreign-born worker categories is problematic for multiple reasons. First, the overly rigid and simplified skills definitions often limit mobility pathways for workers who might have some postsecondary education or training but who lack a four-year degree—middle-skilled workers. In the United States, reports show that about 52 percent of jobs require mid-level skills,[xii] and 69 percent of human resources executives claim that their firm’s performance is often impacted by their inability to attract such talent.[xiii] Additionally, estimates indicate that middle-skill occupations will represent the largest share of overall job openings in the United States through 2024.[xiv] The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), which defines middle-skill jobs as occupations with average wages “in the middle of the occupation-wage distribution”—a definition that does not even reflect the actual skills of the workers—says that these occupations represent slightly over 30 percent of the total employment in member countries.[xv]

Although some countries recently introduced programs for certain middle-skill occupations, such as caregivers, only a few countries’ migration schemes recognize middle-skilled foreign-born workers as a standalone stream.[2] Therefore, middle-skilled workers are often categorized as low-skilled and thus restricted to the same few pathways merely because they do not meet the high-skill threshold, regardless of their having training and certifications in their fields. This is the case in Spain, for example, giving employers very limited options for closing their job gaps by hiring from abroad.[xvi] As a result of such an approach, many foreign-born workers from the construction and health care sectors are considered low-skilled[xvii] even though they possess certifications in their field. They are then offered fewer and more restrictive mobility pathways than workers recognized as high-skilled.

Employing Sectors Need More Skills than Schooling

Another important issue with the skills dichotomy in countries’ labor mobility schemes is that it overlooks other difficult-to-measure skills that workers also bring to the receiving country, such as technical, social, and cultural abilities, and interpersonal competencies. Businesses are increasingly interested in workers with critical thinking, interpersonal, learning, and other soft skills. In a recent survey, the majority (65 percent) of U.S. employers claimed that soft skills are in the highest demand.[xviii] In other words, educational attainment alone cannot fully describe the actual skills of a foreign-born worker. There are other abilities and expertise that workers gain through specialized training or informally by performing their jobs.

The narrowly defined skill levels used in high-income countries’ labor mobility schemes often diminish the value of workers—native- and foreign-born—in occupations typically labeled as low-wage or low-skill. And yet studies show that foreign-born workers, who are considered low-skilled due to their lack of schooling, are “in fact quite skilled.”[xix] A recent study on work and mobility among Mexican migrants working in low-skill occupations in the United States show that a lack of schooling and credentialing does not correlate with a foreign-born worker’s “lack of ability, desire to learn, or ambition to advance in life.” It also found that foreign-born workers with low levels of schooling still bring skills from their home country that they use in the United States. For example, in the construction sector, nearly two-thirds of the interviewed foreign-born workers confirm that they had previous experience in their home countries, and about half say they use these skills at their jobs in the United States. Moreover, agricultural workers, who are often characterized as “easily replaceable, transient, and unskilled labor,” showed “substantial skill transfers, skill development, and social mobility.”[xx] Similar trends were reported in other sectors as well, including retail, hospitality, and personal services.[xxi] Further, the study finds that over three-quarters of the respondents had learned new skills abroad, sometimes through their occupations, including agricultural work, which typically offers only a few mobility pathways.[xxii]

The dichotomy based on workers’ schooling does not reflect the actual skills and value that workers bring to the receiving high-income countries and their societies. It is impossible to fully assess the ability of workers solely based on their schooling. In other words, workers’ abilities represent a “skill mix,” consisting of a wide range of skills and abilities gained through a variety of sources, rather than just through educational institutions. Clearly, the skills dichotomy, often used to create mobility schemes in high-income countries, completely ignores the experiences of workers from previous employment as well as their soft skills and ability to learn, which are often more important to employing sectors seeking to fill these so-called low-skill positions.

The seemingly simple skills dichotomy used for many high-income countries’ mobility schemes prevents employing sectors from bringing in the variety of workers they need, and thus hampers the process of increasing complexity in the involved economies, ultimately limiting their growth and development. For example, the construction industry needs all type of workers, including engineers, construction managers, electricians, carpenters, and laborers.[xxiii] Manufacturing companies hire researchers and scientists as well as machinists, welders, and cutters.[xxiv] However, the structure of mobility systems often makes it more difficult for employers to hire workers from diverse backgrounds because the employer must navigate multiple programs—some for highly skilled workers and others for less skilled workers. Rather than basing mobility systems on a worker’s education level, the receiving countries should consider sector-based schemes focused on the needs of the employing sectors and the overall economy.

Lastly, but perhaps most importantly, while the label low skilled might imply little value, in fact, such workers provide essential services to the public.[xxv] The health care industry, for example, often devalues women’s work, reflected in a 28 percent gender pay gap, with other industries and professions, such as janitors and maids and house cleaners, facing similar challenges.[xxvi] Combined with restrictions on the admission of foreign-born workers imposed by host countries, migration schemes often disproportionately block women’s migration, especially in occupations such as nurses, caregivers, and sometimes even domestic workers, which are not recognized as “skilled” even though they require a certain level of training.[xxvii] However, it is not only women who face devaluation of their work, as the same trends can be seen in other industries that primarily employ male workers, who are also frequently undervalued and face many migration restrictions.

High-Income Countries Face Labor Scarcity

Economists have long argued that the division of labor is the ultimate formula for a country’s wealth. As the “recipe” analogy at the beginning of this note describes, due to the specialization of companies and their workers in a variety of activities, as well as the interactions among them, a country’s economy becomes more complex, ultimately increasing economic efficiency. The complexity of a country’s economy therefore plays a central role in its economic growth and development.

However, due to inevitable demographic changes caused by low fertility rates and aging populations, the workforces of high-income countries are shrinking.[3] This keeps employers from being able to hire enough workers with the required skills. These trends have resulted in an unprecedented scarcity of workers[4]—a problem that employers across industries cannot address by simply increasing wages (table 1).

Table 1. Total Job Scarcity in Select High-Income Countries, Pre-Pandemic

| Country | Total Job Scarcity | Year Reported |

| United States | 7 million | 2019 |

| Germany | 1.6 million | 2018 |

| France | 200,000–330,000 | 2017 |

Sources:

Glassman, Jim. “Help Wanted: Why the US Has Millions of Unfilled Jobs.” JP Morgan, January 29, 2020; Nienaber, Michael. “Labor Shortages May Undermine German Economic Boom: DIHK Survey.” Thomson Reuters, March 13 2018; “France’s New Labour Problem-Skills Shortages.” The Economist, March 8, 2018.

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has caused economic swings as many businesses were forced to close their doors, and millions of employees around the world were furloughed, but long-term demographic trends are unlikely to change. Instead, data suggest that the situation will likely worsen (table 2).[xxviii] Labor mobility can serve as an effective policy tool for increasing the complexity and thereby the overall growth of the economies of both sending and receiving countries. Foreign-born workers, who return home after a time in the receiving country, bring back with them new and more developed skill sets, which allows them to enhance the economies of their countries of origin.[5] At the same time, labor mobility can, at least partly, alleviate the labor scarcity experienced by the employing sectors of receiving countries.

Table 2. Projected Total Job Scarcity in Select High-Income Countries

| Country | Total Projected Job Scarcity | Time Range | Annual Average Growth of Job Scarcity |

| Japan | 6.44 million | 2018–2030 | 535,000 |

| Canada | 2 million | 2014–2031 | 120,000 |

| Poland | 1.5 million | 2019–2025 | 250,000 |

| Switzerland | 500,000 | 2020–2030 | 50,0000 |

| Italy | 300,000 | 2019–2021 | 100,000 |

Sources: “Worker Shortage in Japan to Hit 6.4m by 2030, Survey Finds.” Nikkei Asian Review, October 25, 2018; Miner, Rick. Rep. The Great Canadian Skills Mismatch: People Without Jobs, Jobs Without People and More, March 2014; Wilczek, Maria. “Poland Struggles to Find Workers as Unemployment Hits 28-Year Low.” Al Jazeera, August 29, 2019; “More Jobs—but Are There Enough Workers?” UBS, July 11, 2019; “These Are the Thousands of Job Vacancies That Italy Can’t Fill.” The Local, February 18, 2019.

Therefore, some high-income countries have begun to explore ways to bring workers from abroad. For example, Germany began to enforce its new immigration rules in early 2020 to provide more opportunities for workers from outside the European Union (EU).[xxix] The United Kingdom also introduced a new immigration system in 2020, following the country’s exit from the EU.[xxx] Canada made considerable changes to its system in 2014[xxxi] and launched a number of new pilots in 2019.[xxxii] Nevertheless, rather than focusing on employing sectors’ needs, the new mobility pathways are often targeted primarily at workers they consider skilled.

However, many sectors that struggle the most with worker scarcity need workers typically considered low- or middle-skilled. In the United States, occupations that do not require any degree, including home health and personal care aids, as well as fast-food counter workers and restaurant cooks, were among the jobs with the largest absolute growth in worker demand projected for 2019–2029.[xxxiii] In 2020, European countries reported shortages in occupations such as nursing, plumbers, cooks, heavy truck drivers, and welders.[xxxiv] Although the pandemic exacerbated the alarming need for “low-skilled” essential workers in health care and agriculture, scarcity had already hit these sectors as well as the tourism, construction, and manufacturing sectors in the preceding years. Care work is among the essential sectors hit hardest by worker scarcity, with Australia expecting 250,300 job openings by 2023,[xxxv] and the United States expecting 7.8 million job openings by 2026.[xxxvi] Additionally, the Canadian farmworker deficit is expected to double by 2029 from the 16,500 reported in 2017,[xxxvii] and the Australian[xxxviii] and U.S.[xxxix] agriculture sectors have been stressing the need for more workers as well. Further, 81 percent of U.S. construction businesses reported struggles finding qualified workers in 2020,[xl] expecting to be short 747,000 workers by 2026,[xli] and UK contractors reported difficulties with recruiting as well.[xlii] Even before the pandemic, U.S. construction firms reported 434,000 vacant jobs in 2019,[xliii] and Germany had approximately 225,000 unfilled positions in the construction sector in 2018.[xliv] With regard to the tourism sector, over two-thirds of surveyed German hoteliers and restaurateurs reported that a lack of workers was their top issue.[xlv] Overall, it is clear that sectors employing low-skilled workers in a variety of high-income countries are facing worker scarcity. And yet, the nations have been struggling to introduce an effective labor mobility program to sufficiently fill such gaps.

High-Income Countries Favor High-Skilled Migrants

Despite employers’ proven need to fill their low-skill openings, it has been difficult for foreign-born workers without any or with only limited schooling to come and work in high-income countries. In fact, during the past few years, the political appetite among EU member countries for the opening of new mobility pathways and admitting foreign-born workers is less than what is needed by the employing sectors,[xlvi] even though such pathways could help reduce irregular migration—another issue of concern to many high-income countries over the past few years. However, to achieve the desired reduction, the expansion of new mobility channels would have to be established in a way that sufficiently increases the incentives for workers and employers to avoid irregularity, combined with other enforcement measures.[xlvii] Currently, even when a nation’s government does explore labor mobility as a solution to increasing labor scarcity, the efforts often target workers with college and university degrees.

That shift is dramatic compared to historical approaches toward immigration in high-income countries, such as the United States, Canada, and Australia. While a hundred years ago, these nations’ mobility schemes emphasized attracting laborers[6] to fill low-skill jobs in factories and mines or on farms and ranches, today the focus is shifted toward recruiting science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) and management-level workers.[xlviii] Nowadays, politicians in the OECD member countries compete to attract what they believe to be “the best and brightest”[xlix] while controlling and reducing other migration channels, including low-skilled worker mobility.[l] While mobility channels for high-skilled workers tend to provide permanent pathways to the receiving countries, channels for low-skilled migrants are usually temporary and very restrictive.[li] The temporary pathways tend to be seasonal despite the need of many employing sectors to fill other low-skill year-round jobs. While temporary pathways for low-skilled workers may be more politically feasible, their restrictive nature may ultimately hurt both the employing sectors and foreign-born workers due to the number of barriers and constraints that must be overcome just so the worker can remain in the receiving country for a limited time.

There are very few channels through which employers in high-income countries may bring in nonseasonal low- and middle-skilled workers. For example, the U.S. mobility system currently provides zero pathways for nonseasonal occupations requiring less than a college degree. While there are programs for highly skilled temporary workers with a postsecondary education and for seasonal agricultural and nonagricultural workers,[lii] no pathways exist for workers to fill the country’s year-round shortages in low-skill sectors, such as care work[liii] and certain manufacturing occupations.[liv] Switzerland does not even allow individuals from non-EU countries to work unless they are considered “highly qualified,” which means they must hold a university degree and have professional work experience.[lv] Similarly, the Netherlands only has a few pathways to bring non-EU low- and middle-skilled workers.[lvi]

Some high-income countries appear generally open to receiving more foreign-born workers, but their programs are primarily focused on the admission of highly skilled workers. France, for example, has been relatively more amenable to labor mobility as the country seeks new ways of closing its job gaps. However, its channels have been selective, prioritizing workers with more schooling above others. Despite the growing demand for low- and middle-skilled workers in sectors such as agriculture, hospitality, and care work, the emphasis has been on recalibrating the mobility of highly skilled workers and students, as well as on family and humanitarian migration.[lvii] Although Canada provides opportunities for low-skilled workers to come through its temporary channels, they are, in most cases, disadvantaged compared with high-skilled workers, who have been given a clear path to permanent residency.[7],[lviii] Moreover, the opening to more low-skilled workers in Canada has been accompanied by a series of restrictions imposed on the program regarding employment, social residency, and family reunification.[lix] The United Kingdom’s newly introduced point-based system also disadvantages low-skilled workers[lx] and encourages employers to “move away” from relying on hiring from abroad.[lxi] Greater openness toward highly skilled over less skilled workers has been characteristic of the mobility schemes of many Southeast Asian countries as well. Singapore, for example, has novel policies to attract “foreign talent” and regulations for employing less skilled “foreign workers.” Hong Kong has a strictly regulated program for low-skilled migrant workers and a more open one for those with higher-level skills, under which the worker does not need a job offer and can eventually settle.[lxii]

It is important to note that seasonal work represents a significant exception to the above-described trend, but even those programs are designed to restrict low-skilled workers’ access to host countries. In the United States, for example, the nonagricultural seasonal worker program helps employers fill job vacancies during peak seasons. However, even though the program covers all sectors with seasonal need other than agriculture, it has been restricted by an annual cap of 66,000 workers.[lxiii] Although employers in those sectors have been calling for an increase since the early 2000s when their need began to considerably exceed the 66,000 limit, the quota has remained constant since the 1990s, preventing more workers from entering the country.[8],[lxiv] This trend is apparent also in countries that have recently piloted new programs for admitting seasonal workers. In 2019, the British government announced the beginning of its Seasonal Workers Pilot, or the “Initial Pilot,” through which farmers can recruit a limited number of temporary workers.[9] The original pilot program was set up to provide visas for 2,500 seasonal migrant workers to come to the United Kingdom in 2019; the number increased to 10,000 in 2020;[lxv] and for 2021, the quota has been expanded to 30,000 workers.[lxvi] However, that is still far from filling the 80,000-worker gap reported by UK farmers.[lxvii] And what’s more, on its website, the UK government still calls for the recruitment of domestic workers and automation in effort to “move away from a heavy reliance on low skilled overseas workers.”[lxviii]

The Covid-19 pandemic, which caused an unprecedented shortage of essential workers, forced some high-income countries to implement fast-track immigration measures to address the situation, allowing more foreign-born workers with skill levels categorized as low or middle to come or remain for a longer period. Italy gave 600,000 undocumented migrants work permits in recognition of the need for these workers to provide care and put food on the table during the crisis.[lxix] Portugal has temporarily regularized all migrants who had applied for a residency permit before the declaration of the state of emergency. Despite border closures, Germany, the United Kingdom, Finland, and other countries have made special provisions to fly in seasonal agricultural workers.[lxx],[lxxi]In Canada, Prince Edward’s Island has fast-tracked immigration processes for health workers and truckers; and Nova Scotia has done the same for nurses.[lxxii]

Nevertheless, the argument that high-income countries tend to prefer and favor so-called high-skilled over low-skilled foreign-born workers is also evident in the discrepancy of the rights provided to each of the two groups. As Martin Ruhs suggests in his book The Price of Rights: Regulating International Labor Migration, programs targeting more highly skilled foreign-born workers tend to grant such workers greater rights than do the low-skill programs. This trend stems from the fact that the pool of highly qualified workers who are willing to migrate is relatively small, allowing selected individuals to choose among receiving countries, thereby prompting the competing destinations to offer high wages as well as more substantial rights. On the other hand, because the number of potential foreign-born workers willing to accept low-skill jobs is virtually unlimited, receiving countries often provide them with wages, employment conditions, and rights that violate local laws and are that fall significantly below international standards.[lxxiii] The countries of the Cooperation Council for the Arab States of the Gulf (GCC, formerly known as the Gulf Cooperation Council) are among the most open to low-skilled workers, representing a clear exception to the pattern described above. However, they also provide these individuals with very weak labor standards and limited rights. Singapore is similarly quite open to foreign-born workers while also imposing considerable restrictions on the rights of low-skilled workers. Despite recent efforts to raise the bar on worker protections, numerous reports continue to demonstrate how foreign-born workers’ rights are being abused.[lxxiv]

Why Are Low-Skilled Workers Out of the High-Income Countries’ Spotlight?

Lawmakers’ decisions regarding the regulation of the admission of foreign-born workers depend on national policy goals, such as economic efficiency and national security, given certain constraints, including domestic and international legal restrictions or a limited ability to control immigration flows.[lxxv] According to Ruhs, there are at least three reasons why high-income countries are more likely to favor highly skilled foreign-born workers: (1) they expect that such workers will better complement the existing skills and capital of their population; (2) they value the importance of human capital and knowledge for long-term economic growth as predicted by endogenous growth models; and (3) the dependence of the overall fiscal impact of immigration on workers’ earnings, which tend to be linked to their skills. In other words, a highly skilled foreign-born worker will likely pay more in taxes and be less eligible for welfare benefits than a worker with a lower skill level.

Since high-income countries tend to be quite knowledge-based, their lawmakers tend to think that recruiting “the best and brightest” in the “global competition to attract high-skilled migrants” will further speed up their countries’ technological advancement and development. A powerful lobby has helped shape the narrative around highly skilled workers, as hiring companies tend to be among the largest and best resourced to invest into their industry’s advocacy efforts. In the United States, for example, the most influential petitioners for high-skilled workers are multinational corporations, such as Deloitte, Apple, Cisco, Amazon, and Facebook, each with annual revenues in the billions of dollars. It is useful to compare this to the low-skilled nonagricultural temporary worker program in the United States, which serves companies from sectors such as landscaping and seafood processing, which generate much lower profits. There is nothing wrong with attracting highly skilled workers, but it should not be a country’s sole focus because employing sectors need workers with a wide variety of skills, experiences, and abilities.

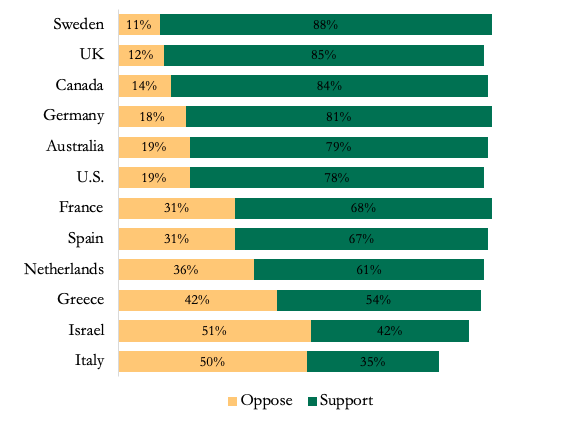

Another explanation typically given by high-income countries to justify their preference for high-skill migration is the public attitude toward low-skilled workers. In 2018, a majority of surveyed individuals in high-income countries, including Sweden, the United Kingdom, Canada, Germany, the United States, and France supported high-skill migration (figure 1),[lxxvi] while at the same time, many saw low-skilled migrants as a burden and believed they were taking jobs away from native-born workers.[lxxvii] Some recent surveys conducted in high-income EU countries and the United States show that most people support quite restrictive immigration measures, especially against migrants from certain ethnic backgrounds, and would like to see a decline in immigration flows to their countries. These attitudes appear to be driven by sociopsychological factors rather than economic concerns.[lxxviii]

Figure 1. Public Support for High-Skill Migration in Select High-Income Countries

Source: Connor, Phillip, and Neil G. Ruiz. “Majority of U.S. Public Supports High-Skilled Immigration.” Pew Research Center’s Global Attitudes Project. Pew Research Center, January 22, 2019. https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2019/01/22/majority-of-u-s-public-supports-high-skilled-immigration/.

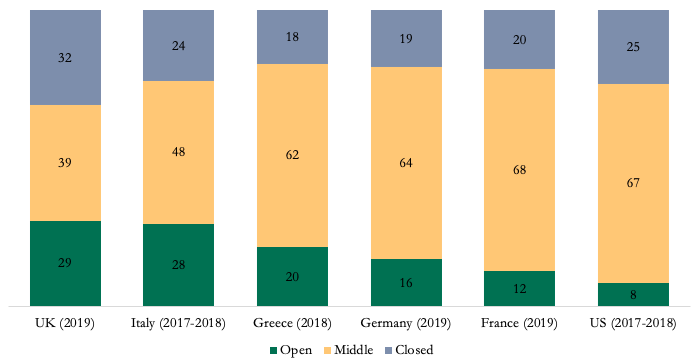

However, recent research showed that most people are not strictly for or against immigration but rather fall somewhere in the middle in that they are anxious, conflicted, or movable. Such individuals are usually quite open to some shifting of their views on immigration (movable), but they have concerns. This group is the most vulnerable to hostile narratives and misinformation spread by certain anti-immigration political actors, making it the main battleground for shaping public attitudes toward migration.[lxxix] At the same time, most people in this category could be convinced that their countries need more foreign-born workers at all skill levels if the argument were approached in a better way, demonstrating the economy’s need for these individuals. To address the hesitance of the “movable middle,” lawmakers in high-income countries should work together with immigration advocates to combat the hostile narratives around migration and come up with strategies to diminish misinformation and demonstrate the benefits that migrants bring to the society.

Figure 2. Grouping People based on their attitudes (including to immigration) in six countries

Source: Butcher, Paul, Helen Dempster, and Alberto-Horst Neidhardt. “Making the ‘Movable’ Middle More Open to Immigration.” MPC Blog. European University Institute, February 26, 2021. https://blogs.eui.eu/migrationpolicycentre/making-the-movable-middle-more-open-to-immigration/.

Despite the hostile narratives around low-skilled foreign-born workers, research reveals how important their roles are to the lives of people in the receiving high-income countries, and how much they increase overall productivity. Foreign-born workers often perform difficult jobs—mowing lawns, picking berries, washing dishes, or building roads, as examples. In other words, such workers add to the economic complexity described by Hausmann, and thereby contribute to the economic growth of the receiving country. Additionally, as foreign-born workers enter occupations that require lower skill levels, native-born workers tend to move away from such jobs and begin to improve their economic status. In the United States, data show that the increase in foreign-born workers entering the country who willing to engage in lower-skill occupations allowed the native-born population to become more educated and skilled and to pursue better jobs.[lxxx] A separate study reveals that low-skill immigration into the United States allows highly skilled women to decrease the amount of time they spend on household work and significantly increase the number of hours they can dedicate to their field, including law or medicine.[lxxxi] Similar research found that the outsourcing of household production to temporary foreign domestic workers significantly contributed to the increased labor force participation of women, especially mothers of young children in Hong Kong.[lxxxii] Overall, the research suggests that immigration reduces the total cost of household services, prompts the native-born workforce to become more productive, and helps highly skilled women work additional hours or have more children.[lxxxiii]

Conclusion

To increase the complexity of their economies and thereby boost economic growth, high-income countries need workers with a broad variety of skills and the ability to learn—not only workers with a particular level of schooling. Given the demographic challenges faced by high-income countries, foreign-born workers could help fill job gaps. However, the traditional dichotomy of low- and high-skilled workers, solely based on an individual’s level of education, prevents their labor mobility systems, which tend to favor high-skilled workers, from bringing in foreign-born workers with a broader variety of skill sets. Moreover, the existing systems tend to ignore the fact that workers learn and gain more skills while on the job in the host country, which benefits both the receiving country and the country of origin as some workers return. A productive society includes people with a broad range of skills that complement each other. Therefore, in lieu of the simplistic skills dichotomy, workers should be seen as offering a “skills mix” composed of all their experiences and abilities gained in and out of school, as well as their interpersonal, communication, cultural, and other social skills. Rather than building mobility pathways based on a worker’s level of schooling, receiving countries should consider schemes based on the needs of their employing sectors.

Opening more sector-focused mobility pathways could also positively impact people from both receiving and sending nations. Such an expansion of pathways could enable more native-born workers to access additional education and skills and thereby improve their economic status while also serving as a crucial part of a nation’s development strategy by allowing foreign-born workers to return to their countries of origin with experiences and skills gained abroad, thereby helping their families and communities escape poverty.

[1] Sometimes referred to as unskilled.

[2] For example, New Zealand recognizes mid-level skills in its labor mobility scheme.

[3] Based on the United Nations’ zero migration scenario, the working-age populations of OECD countries will decline by more than 92 million by 2050, while at the same time the elderly population (over age 65) will grow by more than 100 million people.

[4] More on worker scarcity can be found in LaMP’s separate policy note here.

[5] More on how labor mobility helps workers escape poverty can be found in a previous LaMP’s note here.

[6] The focus was on bringing these workers from northwestern Europe, especially, the British Isles.

[7] Canada has recently decided to lower the number of points one needs to enter the country through its point-based system to a record low, allowing some low-skilled workers to settle in the country. However, the new measure is mostly focused on skilled migrants who are already in the country rather than new temporary workers that still face other barriers to entry.

[8] Even when the government decided to increase the cap in FY2017, FY2018, and FY2019 by 15,000, 15,000, and 30,000, respectively, through a one-time regulation, the total number of admitted workers remained well below the employers’ need.

[9] The program has been created in reaction to farmers’ worriers about potential lack of seasonal workers after the country exited the EU and introduced its new points-based immigration system that focuses mostly on attracting high-skilled workers as discussed above. Moreover, in summer 2020 during the first wave of COVID-19, the country launched its ‘Pick for Britain’ campaign that attracted only about 8,000 locals, way below the estimated 80,000 needed workers, which also added to the farmers’ worries.

[i] Hidalgo, César A., and Ricardo Hausmann. “The Building Blocks of Economic Complexity,” June 30, 2009. https://www.pnas.org/content/106/26/10570#sec-7.

[ii] Clemens, Michael, and Kate Gough. “Can Regular Migration Channels Reduce Irregular Migration? Lessons for Europe from the United States.” Center for Global Development, February 2018. https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/can-regular-migration-channels-reduce-irregular-migration.pdf.

[iii] Best, E. (2017, May 3). How U.S. Employment Affects Returning Migrants. Retrieved October 25, 2020, from https://psmag.com/news/when-migrant-workers-return-home-24836.

[iv] Debnath, P. (2016, November). Leveraging Return Migration for Development: The Role of Countries of Origin (Rep.). Retrieved October 25, 2020, from KNOMAD website: https://www.knomad.org/sites/default/files/2017-04/WP%20Leveraging%20Return%20Migration%20for%20Development%20-%20The%20Role%20of%20Countries%20of%20Origin.pdf

[v] Dumont, J.-C., and G. Spielvogel. “Return Migration: A New Perspective.” In International Migration Outlook, Part III. 2008. Paris: OECD Publishing.

[vi] Iskander, Natasha, and Nichola Lowe. “The Transformers: Immigration and Tacit Knowledge Development.” SSRN. NYU Wagner Research Paper No. 2011–01, January 23, 2011. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1745082.

[vii] Weinar, Agnieszka, and Amanda von Koppenfels Klekowski. “Highly Skilled Migration: Concept and Definitions.” SpringerLink. IMISCOE Short Reader, May 28, 2020. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-42204-2_2.

[viii] Moriarty, Andrew. “High Skilled Immigration – 5 Things to Know.” FWD.us, September 8, 2020. https://www.fwd.us/news/high-skilled-immigration-5-things-to-know/.

[ix] “The Guide to Visa Types and Work Permit Requirements.” How to get a Work Permit and Visa for Spain.InterNations GO!, September 14, 2020. https://www.internations.org/go/moving-to-spain/visas-work-permits.

[x] “Point-Based Preference Immigration Treatment.” Highly Skilled Foreign Professional Visa. June Advisors Group. Accessed April 9, 2021. https://www.juridique.jp/visa/hsp.php.

[xi] “Overhauling the Temporary Foreign Worker Program.” Canada.ca. Government of Canada. Accessed April 9, 2021. https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/services/foreign-workers/reports/overhaul.html.

[xii] “The Skills Mismatch.” Skills Mismatch. National Skills Coalition. Accessed April 9, 2021. https://www.nationalskillscoalition.org/skills-mismatch/.

[xiii] Burrowes , Jennifer, Alexis Young, Joseph Fuller , and Manjari Raman. “Bridge the Gap: Rebuilding America’s Middle Skills.” Harvard Business School. Accessed April 9, 2021. https://www.hbs.edu/competitiveness/Documents/bridge-the-gap.pdf.

[xiv] Kosten, Dan. “Immigrants as Economic Contributors: They Are the New American Workforce.” National Immigration Forum, June 5, 2018. https://immigrationforum.org/article/immigrants-as-economic-contributors-they-are-the-new-american-workforce/.

[xv] “What Is Happening to Middle-Skill Workers?” OECD Employment Outlook 2020 : Worker Security and the COVID-19 Crisis: OECD iLibrary. OECD, July 7, 2020. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/c9d28c24-en/index.html?itemId=%2Fcontent%2Fcomponent%2Fc9d28c24-en.

[xvi] Hooper, Kate. “Spain’s Labour Migration Policies in the Aftermath of Economic Crisis.” Migration Policy Institute Europe, 2019. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/publications/MPIE-SpainMigrationPathways-Final.pdf.

[xvii] Speare-Cole, Rebecca, and Emily Lawford. “What Is the Points-Based Immigration Bill, and What Is Classed as a ‘Low-Skill’ Job?” London Evening Standard. Evening Standard, July 13, 2020. https://www.standard.co.uk/news/politics/uk-immigration-points-based-system-threshold-unskilled-job-a4367206.html.

[xviii] Ashford, Ellie. “Employers Stress Need for Soft Skills.” Community College Daily. Community College Daily, January 16, 2019. https://www.ccdaily.com/2019/01/employers-stress-need-soft-skills/#:~:text=Among%20soft%20skills%2C%20employers%20said,Effective%20communication%20(69%20percent).

[xix] Hagan, Jacqueline. “Defining Skill: The Many Forms of Skilled Immigrant Labor.” American Immigration Council, November 18, 2018. https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/defining-skill-many-forms-skilled-immigrant-labor.

[xx] Hagan, Jacqueline. “Defining Skill: The Many Forms of Skilled Immigrant Labor.” American Immigration Council, November 18, 2018. https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/defining-skill-many-forms-skilled-immigrant-labor.

[xxi] Hagan, Jacqueline. “Defining Skill: The Many Forms of Skilled Immigrant Labor.” American Immigration Council, November 18, 2018. https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/defining-skill-many-forms-skilled-immigrant-labor.

[xxii] Hagan, Jacqueline. “Defining Skill: The Many Forms of Skilled Immigrant Labor.” American Immigration Council, November 18, 2018. https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/defining-skill-many-forms-skilled-immigrant-labor.

[xxiii] Torpey, Elka. “Careers in Construction: Building Opportunity.” Career Outlook. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, August 2018. https://www.bls.gov/careeroutlook/2018/article/careers-in-construction.htm.

[xxiv] “Two Million Vacant Manufacturing Jobs by 2025…How Can We Tackle the Skills Gap?” GlobalTranz Enterprises, LLC., August 20, 2015. https://www.globaltranz.com/manufacturing-jobs-skills-gap/.

[xxv] Gardner, Mary. “The Case for Low-Skilled Immigrants.” Opinion. The Hill, June 14, 2018. https://thehill.com/opinion/immigration/391968-the-case-for-low-skilled-immigrants?rl=1.

[xxvi] O’Donnell, Megan, and Samantha Rick. “A Gender Lens on COVID-19: Investing in Nurses and Other Frontline Health Workers to Improve Health Systems.” Commentary and Analysis. Center For Global Development, March 25, 2020. https://www.cgdev.org/blog/gender-lens-covid-19-investing-nurses-and-other-frontline-health-workers-improve-health-systems.

[xxvii] Smith, Rebekah, and Megan O’Donnell. “COVID-19 Pandemic Underscores Labor Shortages in Women-Dominated Professions.” Commentary and Analysis. Center For Global Development, May 13, 2020. https://www.cgdev.org/blog/covid-19-pandemic-underscores-labor-shortages-women-dominated-professions.

[xxviii] Mallet , Victor, Daniel Dombey , and Martin Arnold . “Pandemic Blamed for Falling Birth Rates across Much of Europe.” Coronavirus economic impact. Financial Times, March 10, 2021. https://www.ft.com/content/bc825399-345c-47b8-82e7-6473a1c9a861.

[xxix] MacGregor, Marion. “Europe: Few Routes for Unskilled Migrants.” Understanding Europe. Infomigrants, January 27, 2021. https://www.infomigrants.net/en/post/29885/europe-few-routes-for-unskilled-migrants.

[xxx] “New Immigration System: What You Need to Know.” GOV.UK. Home Office and UK Visas and Immigration, January 28, 2020. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/new-immigration-system-what-you-need-to-know#skilled-workers.

[xxxi] “Overhauling the Temporary Foreign Worker Program.” Canada.ca. Government of Canada. Accessed April 9, 2021. https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/services/foreign-workers/reports/overhaul.html.

[xxxii] O’Doherty, Hugo. “Canada Immigration Levels Plan: 2019-2021.” Immigration. Moving2Canada, October 31, 2018. https://moving2canada.com/canada-immigration-levels-plan-2019-2021/.

[xxxiii] Clemens, Michael, Reva Resstack, and Cassandra Zimmer. “The White House and the World: Harnessing Northern Triangle Migration for Mutual Benefit.” The White House and the World – Harnessing Northern Triangle Migration for Mutual Benefit. Center for Global Development, December 2020. https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/harnessing-northern-triangle-migration-for-mutual-benefit.pdf.

[xxxiv] McGrath, John. “Analysis of Shortage and Surplus Occupations 2020.” Employment, Social Affairs & Inclusion. European Commission, January 12, 2020. https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=738&langId=en&pubId=8356&type=2&furtherPubs=no.

[xxxv] Darby, Fi. “10 High Demand Jobs to Look out for in 2020.” SkillsTalk. UpSkilled, December 26, 2019. https://www.upskilled.edu.au/skillstalk/high-demand-jobs-2020.

[xxxvi] Campbell, Stephen. “New Research: 7.8 Million Direct Care Jobs Will Need to Be Filled by 2026.” PHI, January 24, 2019. https://phinational.org/news/new-research-7-8-million-direct-care-jobs-will-need-to-be-filled-by-2026/.

[xxxvii] Nosowitz, Dan. “Canada Has A Huge Agricultural Labor Shortage.” Modern Farmer, July 19, 2019. https://modernfarmer.com/2019/07/canada-has-a-huge-agricultural-labor-shortage/.

[xxxviii] “4 Opportunities to Fix Australia’s Agriculture Labour Crisis.” Agricrew. Accessed July 7, 2020. https://www.agricrew.com.au/news/4-opportunities-to-fix-australia-s-agriculture-labour-crisis/45184/.

[xxxix] Duvall, Zippy. “Another Year of Farm Labor Shortages.” American Farm Bureau Federation – The Voice of Agriculture, July 10, 2019. https://www.fb.org/viewpoints/another-year-of-farm-labor-shortages.

[xl] “Strong Demand For Work Amid Stronger Demand For Workers: The 2020 Construction Hiring And Business Outlook.” Associated General Contractors of America, 2019. https://www.agc.org/sites/default/files/Files/Communications/2020%20Construction%20Hiring%20and%20Business%20Outlook%20Report.pdf.

[xli] De Lea, Brittany. “As Construction Worker Shortage Worsens, Industry Asks Government for Help.” Fox Business, August 27, 2019. https://www.foxbusiness.com/economy/construction-worker-shortage-worsening.

[xlii] Price, David. “Labour Shortages Could Raise Rates ‘at Least 10%’.” Construction News, January 29, 2021. https://www.constructionnews.co.uk/brexit/labour-shortages-could-raise-rates-at-least-10-29-01-2021/.

[xliii] Cilia, Juliette. “The Construction Labor Shortage: Will Developers Deploy Robotics?,” July 31, 2019. https://www.forbes.com/sites/columbiabusinessschool/2019/07/31/the-construction-labor-shortage-will-developers-deploy-robotics/.

[xliv] Milovanovic, Vladimir. “Labour Shortage Set to Escalate Construction Costs in 2019.” 3lite, November 28, 2018. https://3lite.co/2018/11/28/labour-shortage-set-to-escalate-construction-costs-in-2019/.

[xlv] Rogers, Iain. “Germany’s Tourism Success Story Threatened by Worker Shortage.” Skift, December 24, 2019. https://skift.com/2019/12/24/germanys-tourism-success-story-threatened-by-worker-shortage/.

[xlvi] Chrysoloras, Nikos. “Europe’s Bid for Self-Reliance Overlooks Need for Human Capital.” Bloomberg, February 16, 2021. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/newsletters/2021-02-16/supply-chains-latest-eu-self-reliance-overlooks-human-shortages.

[xlvii] Clemens, Michael, and Kate Gough. “Can Regular Migration Channels Reduce Irregular Migration? Lessons for Europe from the United States.” Center for Global Development, February 2018. https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/can-regular-migration-channels-reduce-irregular-migration.pdf.

[xlviii] Chiswick , Barry R. “Immigration: High-Skilled versus Low-Skilled Labour?” Australian Government. Productivity Commission. Accessed April 9, 2021. https://www.pc.gov.au/research/supporting/sustainable-population/05-population-chapter03.pdf.

[xlix] Kapur , Devesh, and John McHale. “Give Us Your Best and Brightest: The Global Hunt for Talent and Its Impact on the Developing World.” Center For Global Development, September 1, 2005. https://www.cgdev.org/publication/9781933286037-give-us-your-best-and-brightest-global-hunt-talent-and-its-impact-developing-world.

[l] Czaika, Mathias, and Christopher R. Parsons. “The Gravity of High-Skilled Migration Policies.” KNOMAD, March 2016. https://www.knomad.org/sites/default/files/2017-04/KNOMAD%20Working%20Paper%2013%20HighSkilledMigration_0.pdf.

[li] Ruhs, Martin. “The Price of Rights: Regulating International Labor Migration.” Princeton University. Princeton University Press, August 25, 2013. https://press.princeton.edu/books/hardcover/9780691132914/the-price-of-rights.

[lii] Felter, Claire. “U.S. Temporary Foreign Worker Visa Programs.” Council on Foreign Relations. Council on Foreign Relations, July 7, 2020. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/us-temporary-foreign-worker-visa-programs.

[liii] Darby, Fi. “10 High Demand Jobs to Look out for in 2020.” Upskilled, December 26, 2019. https://www.upskilled.edu.au/skillstalk/high-demand-jobs-2020.

[liv] Sundblad, Willem. “The Manufacturing Labor Shortage Is Still Coming, Stay Prepared.” Forbes, April 23, 2020. https://www.forbes.com/sites/willemsundbladeurope/2020/04/23/the-labor-shortage-is-still-coming-stay-prepared/?sh=6f5ae3c03892.

[lv] “Non-EU/EFTA Nationals.” State Secretariat for Migration. Switzerland, December 31, 2020. https://www.sem.admin.ch/sem/en/home/themen/arbeit/nicht-eu_efta-angehoerige.html.

[lvi] “Working in the Netherlands.” Immigration and Naturalisation Service. Ministry of Justice and Security. Accessed April 15, 2021. https://ind.nl/en/work/working_in_the_Netherlands/Pages/default.aspx.

[lvii] Beirens, Hanne, Camille Le Coz, Kate Hooper, Karoline Popp, Jan Schneider, and Jeanette Süß. “Legal Migration for Work and Training: Mobility Options to Europe for Those Not in Need of Protection.” Expert Council of German Foundations on Integration and Migration. Migration Policy Institute Europe, 2019. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/publications/SVR-Final%20Report-FINALWEB-Updated.pdf.

[lviii] Nakache, Delphine. “Why Canada’s Immigration Policy Is Unfair to Temporary Foreign Workers.” World of IDEAS. University of Ottawa, 2012. https://socialsciences.uottawa.ca/international-development-global-studies/sites/socialsciences.uottawa.ca.international-development-global-studies/files/dnakache_worldideas.pdf.

[lix] Ruhs, Martin. “The Price of Rights: Regulating International Labor Migration.” Princeton University. Princeton University Press, August 25, 2013.

[lx] “What’s a Skilled Worker? And Other Immigration Questions.” BBC News, February 22, 2020. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-politics-uk-leaves-the-eu-51572789.

[lxi] “The UK’s Points-Based Immigration System: Policy Statement.” GOV.UK. UK Government, February 19, 2019. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-uks-points-based-immigration-system-policy-statement/the-uks-points-based-immigration-system-policy-statement.

[lxii] Ruhs, Martin. “The Price of Rights: Regulating International Labor Migration.” Princeton University. Princeton University Press, August 25, 2013.

[lxiii] Bruno, Andorra. “The H-2B Visa and the Statutory Cap: In Brief.” Federation of American Scientists. Congressional Research Service, April 17, 2018. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/homesec/R44306.pdf.

[lxiv] Bruno, Andorra. “The H-2B Visa and the Statutory Cap: In Brief.” Federation of American Scientists. Congressional Research Service, April 17, 2018. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/homesec/R44306.pdf.

“Report of the Visa Office 2019.” Travel.State.Gov. U.S. Department of State. Accessed April 15, 2021. https://travel.state.gov/content/travel/en/legal/visa-law0/visa-statistics/annual-reports/report-of-the-visa-office-2019.html.

“Performance Data.” Employment and Training Administration . U.S. Department of Labor . Accessed April 15, 2021. https://www.dol.gov/agencies/eta/foreign-labor/performance.

[lxv] “Farmers Welcome Extension to Seasonal Workers Pilot in 2021.” Tallents Solicitors, January 18, 2021. https://www.tallents.co.uk/seasonal-workers-pilot/.

[lxvi] “Seasonal Workers Pilot Request for Information.” GOV.UK. UK Government, January 19, 2021. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/seasonal-workers-pilot-request-for-information/seasonal-workers-pilot-request-for-information.

[lxvii] Lindsay, Frey. “With No EU Workers Coming, The U.K. Agriculture Sector Is In Trouble.” Forbes Magazine, March 24, 2020. https://www.forbes.com/sites/freylindsay/2020/03/24/with-no-eu-workers-coming-the-uk-agriculture-sector-is-in-trouble/?sh=102480f7363c.

[lxviii] “Seasonal Workers Pilot Request for Information.” GOV.UK. UK Government, January 19, 2021. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/seasonal-workers-pilot-request-for-information/seasonal-workers-pilot-request-for-information.

[lxix] Kington, T. “Italy to give 600,000 migrants the right to stay.” The Times. May 07, 2020. https://www.thetimes.co.uk/edition/world/italy-to-give-600-000-migrants-the-right-to-stay-n3l8935bj

[lxx] Eddy, M. “Farm Workers Airlifted Into Germany Provide Solutions and Pose New Risks.” New York Times. May 18, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/18/world/europe/coronavirus-german-farms-migrant-workers-airlift.html?smid=tw-share

[lxxi] Corker, S. “Eastern Europeans to be flown in to pick fruit and veg.” BBC. April 16, 2020. https://www.bbc.com/news/business-52293061

[lxxii] Moroz, H., Testaverde, M. and Shrestha, M. “Potential Responses to the COVID-19 Outbreak in Support of Migrant Workers.” COVID Living Paper. World Bank Group. May 26, 2020. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/428451587390154689/Potential-Responses-to-the-COVID-19-Outbreak-in-Support-of-Migrant-Workers-May-26-2020

[lxxiii] Ruhs, Martin. “The Price of Rights: Regulating International Labor Migration.” Princeton University. Princeton University Press, August 25, 2013.

[lxxiv] Ruhs, Martin. “The Price of Rights: Regulating International Labor Migration.” Princeton University. Princeton University Press, August 25, 2013.

[lxxv] Ruhs, Martin. “The Price of Rights: Regulating International Labor Migration.” Princeton University. Princeton University Press, August 25, 2013.

[lxxvi] Connor, Phillip, and Neil G. Ruiz. “Majority of U.S. Public Supports High-Skilled Immigration.” Pew Research Center’s Global Attitudes Project. Pew Research Center, January 22, 2019. https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2019/01/22/majority-of-u-s-public-supports-high-skilled-immigration/.

[lxxvii] “Low-Skilled Immigrants May Make Some Poor Brits Poorer. Here’s Why That’s Not the Whole Story.” Our Economy, October 7, 2019. https://www.ecnmy.org/engage/low-skilled-immigrants-may-make-poor-brits-poorer-heres-thats-not-whole-story/.

[lxxviii] Javdani, Mohsen. “Public Attitudes toward Immigration-Determinants and Unknowns.” IZA World of Labor, March 2020. https://wol.iza.org/articles/public-attitudes-toward-immigration-determinants-and-unknowns/long.

[lxxix] Butcher, Paul, Helen Dempster, and Alberto-Horst Neidhardt. “Making the ‘Movable’ Middle More Open to Immigration.” MPC Blog. European University Institute, February 26, 2021. https://blogs.eui.eu/migrationpolicycentre/making-the-movable-middle-more-open-to-immigration/.

[lxxx] Bier, David J. “Immigrants Are Not Causing Low‐ Skill Natives to Quit Working.” CATO At Liberty. CATO Institute, September 12, 2016. https://www.cato.org/blog/immigrants-are-not-causing-low-skill-natives-quit-working.

[lxxxi] Cortés, Patricia, and José Tessada. “Low-Skilled Immigration and the Labor Supply of Highly Skilled Women.” JSTOR. American Economic Association, July 2011. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41288640?refreqid=excelsior%3A63751d0b3953375e879b8404b8779a61&seq=1.

[lxxxii] Cortés, Patricia, and Jessica Pan. “Outsourcing Household Production: Foreign Domestic Workers and Native Labor Supply in Hong Kong.” JSTOR. The University of Chicago Press, April 2013. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/668675?refreqid=excelsior%3A64383946466ede1f73843523ae3c2e64&seq=1.

[lxxxiii] Furtado, Delia. “Immigrant Labor and Work-Family Decisions of Native-Born Women.” IZA World of Labor. University of Connecticut, USA, and IZA, Germany, April 2015. https://wol.iza.org/uploads/articles/139/pdfs/immigrant-labor-and-work-family-decisions-of-native-born-women.pdf.