Why Labor Mobility?

The ‘Why Labor Mobility?’ series of policy notes explores the historic need for labor mobility from the lens of key actors:

- receiving countries

- sending countries

- employers

- workers

- ‘mobility industry’

This third note in the series focuses on the perspective of governments in low-income sending countries facing rapidly growing youth populations.

Key Points

- Low-income countries face significant increases in their youth populations – the opposite demographic challenge than high-income countries whose populations are shrinking.

- Traditional paths to job creation through manufacturing are closed off to these countries because of labor-saving technologies and the established position of Asian manufacturing exporters.

- Labor mobility offers a jobs solution and is a powerful development tool through remittances and skill accumulation.

- However, there are several factors limiting sending countries’ ability to unlock the potential of labor mobility for their people, including the (false) belief that it reflects a failure of development.

- Solving these challenges requires a multi-faceted effort with receiving country governments, employers, and a quality mobility industry.

Introduction

Low-income countries face significant increases in their youth populations – the opposite demographic challenge than high-income countries whose populations are shrinking. This poses significant risks associated with youth underemployment, as historic pathways to jobs creation through manufacturing growth are now for the most part closed off for low-income countries, making it increasingly difficult for these countries to create the number of jobs needed to absorb their growing youth populations. However, this also a historic opportunity to bridge international labor markets – rotational labor mobility from low-income to high-income countries can address labor scarcity caused by demographic decline in high-income countries, while increasing the share of low-to-mid skilled youth in burgeoning working age populations of low-income countries that are engaged in quality employment at any point in time.

Such labor mobility offers transformative benefits for sending countries; beyond offering quality employment opportunities for their workers, associated remittances and skill accumulation can effect powerful positive change on development outcomes in these countries. Ironically, labor mobility has often been viewed as a failure of development. As a result, governments in low-income countries have more often acted to discourage rather than promote it. This view misunderstands both the drivers as well as benefits of labor mobility, and prevents governments from working to overcome sending-side challenges to mobility. A partnership approach can help overcome these challenges, unlocking life-changing opportunities for their growing youth populations.

The youth bulge and labor mobility as an employment strategy

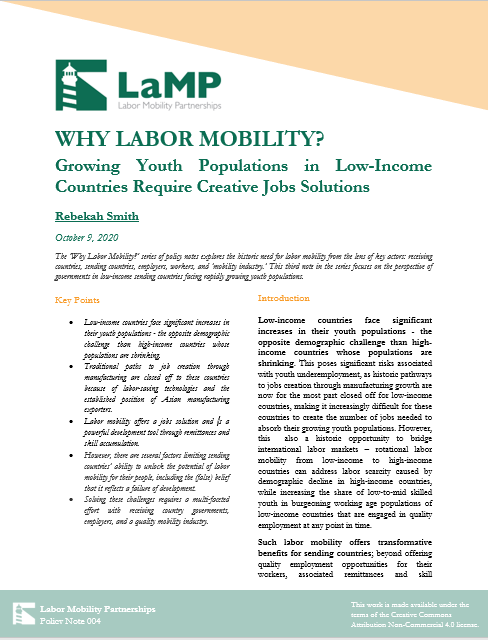

In previous notes, we have discussed the demographics in high-income countries, characterized by dramatically aging populations in significant need of workers. Many low-income countries face precisely the opposite demographic challenge: burgeoning youth populations which outstrip job growth. The total population in developing countries has been growing and is projected to continue increasing over the coming decades—in a status quo scenario, with a rising and large working-age population. The 2015 statistics from the Population Division of UN DESA estimate that by 2050 the working-age population in these regions/countries will increase by millions, and in the cases of sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, hundreds of millions.[i] The numbers in Figure 1 represent the net absolute increase in the number of workers in the workforce between 2015 and 2050.

Figure 1: Change in working-age population (20–64) between 2015 and 2050[ii]

Source: UN DESA, Population Division (2015)

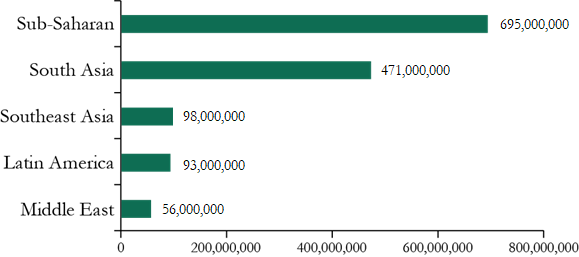

Job growth is not likely to be able to absorb all of these new labor market entrants, particularly as manufacturing is no longer a strong strategy for job creation. [1]Even maintaining current employment levels, as many as half of the new working age people in these regions would struggle to find productive employment. Figure 2 below shows how many of the total number of new working age people by 2050 would likely be able to find employment versus those who would likely have limited employment opportunities, if the current employment rates were maintained. Under this scenario, an estimated 590 million of the 1.4 billion new working age people would have limited access to employment opportunities. Yet even this is an optimistic forecast, as the current projections of job growth would not be sufficient to absorb even the remaining 819 million. For example, the World Bank estimates that the working-age population of Africa will grow by approximately 450 million people between 2015 and 2035, only 100 million of whom can expect to find stable employment opportunities at current projections of job creation.[iii] This leaves a remaining 350 million young people in a 20 year period without productive employment.

Figure 2: At current employment rates, only 819 million of the new working age people would enter employment

Sources: UN DESA, Population Division (2015); ILO (2019).

The jobs challenge for these youth-rich countries is compounded by trends of low-skilled labor in an era of technology innovation biased toward “labor-saving.” The scarcity of low-skilled, low-cost labor in richer, more advanced economies has given rise to labor-saving technological progress that has substituted workers in labor-intensive manufacturing jobs. With openness to trade, Asian countries such as China and South Korea, with a comparative advantage in low-cost and labor-intensive activities, were able to industrialize, increasing their manufacturing output and thus their exports. These exports in turn replaced products made by advanced economies with high labor costs. In this way, such Asian economies achieved new levels of growth.

For current low-income countries, the introduction of widespread labor-saving technologies has made it difficult to create jobs by increasing manufacturing output. Even the most ‘labor intensive’ parts of manufacturing are now much less labor intensive than they were when Asian exporters used this as a strategy towards jobs growth. The “elasticity of manufacturing employment to manufacturing value added” has fallen in most places; in Asian economies it has fallen from ~1 to ~0.2, implying that you would need five times at much manufacturing value added to get a single job compared to historically.[iv] The decline in the labor intensiveness of manufacturing means that the future of jobs growth everywhere (in high- and low- income countries alike) are in services.

Moreover, the established position of the Asian exporters has made it difficult for current-low income countries to compete on manufacturing exports; again blocking them from replicating these Asian countries’ path to jobs growth (a view referred to amongst economists as the Flying Geese paradigm). This shift is happening at significantly lower income level than enjoyed by advanced economies and Asian exporters.[v] With their path to development altered by trade and technology, poorer countries will face the challenge of employing 1.4 billion workers, whose path to traditional labor-intensive manufacturing industries will be virtually blocked.

Growing youth underemployment presents a number of concerns for government officials in low-income countries. Studies show that underemployment at the beginning of a young persons’ career negatively impacts social cohesion, long physical[vi] and mental health,[vii] as well as long term employment and income outcomes.[viii] Youth bulges are also associated with increased risks of violent conflict,[ix] and youth underemployment in particular aggravates these risks. These risks make expanding youth employment opportunities a key policy priority for low-income countries, yet options are constrained (as noted above) by the changing nature of trade and technology which had historically provided the countries with a path to job creation.

Benefits of labor mobility to the sending country

Despite these risks and constraints, growing youth population in low-income countries presents an enormous opportunity. As we have previously discussed in another LaMP note, high-income countries are rapidly aging. With a shrinking working-age and growing elderly populations, high-income countries will need additional 400 million new workers over the next 30 years in order to maintain their safety nets and economic systems. This massive need for workers offers a path to quality employment for a large share of new working age people in low-income countries who are not projected to currently be absorbed by their domestic labor markets.

Beyond alleviating employment pressures, there are a number of additional reasons sending country governments should be interested in actively expanding overseas employment opportunities for their workers. The largest positive impacts of labor mobility are those going directly to the workers, which we will explore in the next note in this series. However, there are significant benefits to the sending country society as a whole. Chief among these benefits are remittance inflows and skill acquisition.

Remittances

Remittances are as large or larger than foreign aid in many sending countries. As of 2018, global remittances estimates stood at USD 689 billion, USD 529 billion of which went to low-income countries.[x] This is approximately at the same level as foreign direct investment (FDI); when China is excluded remittances are larger than FDI as the biggest source of external financing.[xi] In his book A Good Provider is One Who Leaves, Jason DeParle offers further insight into how important these flows are to many countries: “Migration is the world’s largest anti-poverty program…Mexico earns more from remittances than from oil. Sri Lanka earns more from remittances than from tea.”[xii]

Remittances are likely more powerful in improving well-being in sending countries than other external financing, as they flow directly into households who are able to use them to bolster their consumption and education and health spending.[xiii] They have been shown to be powerful engines of change in remittance-receiving countries; for example, Nepal was able to reduce its poverty headcount from 45 percent to 15 percent over a 20-year period, despite low growth rates. This was in large part due to remittances, which accounted for 40 percent of the decline in the poverty headcount.[xiv] Remittances were responsible for poverty reductions of five percentage points in Ghana, six points in Bangladesh, and eleven points in Uganda.[xv] More broadly, a study of seventy-one low-income countries found that a 10 percent rise in remittances cut the poverty headcount by 3.5 percent (double the poverty reduction of a comparable rise in domestic growth).[xvi] The Philippines hosts an annual welcome home ceremony at Christmas for workers returning home, greeting them as “heroes” for all of the money they send back home throughout the year.[xvii]

Remittances offer important benefits for the economies of sending countries at a macro level. As a sizable inflow of foreign exchange, remittances can have a positive balance of payment effect, relaxing foreign exchange constraint and allowing for the import of investment goods (e.g., for construction of infrastructure and housing).[xviii] Remittances can further be used as collateral for international borrowing, as seen in the cases of Mexico, Brazil, and Turkey.[xix]

Remittances are a powerful tool to improving well-being for families in sending countries. As noted above, remittances have been responsible for lifting many recipient families out of poverty, as measured by poverty headcounts. In the Philippines, research shows that an 10 percent increase in income due to remittances reduced the poverty rate among recipient households by 2.8 percentage points.[xx] Further, the same study showed that increases in remittances led to increases in school attendance, decreases in child labor, and increased investment in capital-intensive businesses.[xxi] For families receiving remittances in Afghanistan, remittances averaged USD 1,680 annually, accounting for more than half of their income and were consumed in basic needs.[xxii] As noted above, remittances are also shown to increase education and health spending, resulting in proven positive impacts on nutrition standards,[xxiii] healthcare,[xxiv] and children’s school attendance[xxv] and reducing child mortality.[xxvi] Remittances inflows are counter-cyclical in sending countries, stabilizing income and insulating families of migrants from adverse economic shocks.[xxvii]

There is much discussion around remittances as a potential source of investment financing, but evidence shows that they are more often used for household consumption. There have certainly been places where remittances have increased investment in small enterprises; scattered data suggests that resources accumulated while working abroad are often intended for investment in building a house, starting a business, and financing own education plans.[xxviii] However, evidence of remittances being funneled as investment into industry is scant, and it appears more common for them to go into household consumption and health and education spending. While this does not make them any less of a positive influence (indeed, they are being funneled directly into improving well-being for these families), it is important to set expectations of what remittances likely will and will not do.

Skill Accumulation

Workers employed overseas accumulate skills which they then bring back upon their return home. Return from abroad often allows returnees to capitalize on their acquired skills to secure a more highly skilled job (with a better salary) than they would have if they had not migrated.[xxix] Workers gain skills abroad due to on-the-job training, firm- and non-firm-specific formal training, and firm-provided external training courses on a mandated or voluntary basis. As many as half of the skilled migrants working abroad eventually come home, bringing these new skills and connections with them.[xxx] Some rotational schemes have skill accumulation baked into the design; for example, India’s agreement with Japan through the Technical Intern Training Program is considered a “win-win” because Indian workers are trained to Japanese standards and then return to India.[xxxi]

Such upskilling measures have a potential effect on the home country if returnees have new qualifications that the home country can and is willing to use. Research on return migration to Brazil, Chile, and Costa Rica indicates that returnees are overrepresented in highly skilled occupations and underrepresented in least-skilled trades.[xxxii] When Indian- and Chinese-born software engineers returned following the U.S. dotcom bubble,[2] they were evidenced to have transferred institutional and technical knowledge and techniques to their home countries.[xxxiii] When the Greek sovereign debt crisis sparked a return wave of Albanians, more than half of the returnees took jobs as skilled workers in the industries they were employed in in Greece and many engaged in entrepreneurship using techniques they had learned in Greece, creating jobs for themselves and for non-migrants. Researchers concluded that this skill transfer allowed for intensive agriculture to spread in Albania and foster more productive activities, raising output and wages in the sector.[xxxiv]

This challenges the traditional ‘brain drain’ narrative, which has been a barrier to sending countries engaging on labor mobility. The ‘brain drain’ narrative argues that skilled migration depletes the stock of human capital in sending countries and hurts their prospects of economic development.[xxxv] This narrative has dominated the migration policy discourse in sending countries, and has been a key reason why more countries facing youth bulges have not pursued labor mobility as an employment strategy. These concerns stem from the fact that skilled migration constitutes a disproportionately high share of total migration. Using a measure of a “brain drain rate,”[3] Gibson and McKenzie find that this rate for tertiary-educated individuals is 7.3 times that of individuals with primary education and 3.5 times that of individuals with secondary education.[xxxvi]

The concern that this emigration results in shortages of skilled[4] workers in sending countries and worsens development outcomes is not borne out by the evidence. OECD analysis assessed 54 countries experiencing critical health staff shortfalls. The analysis shows that the estimated critical health staff shortage is five times the number of health staff who have emigrated and concludes that “although migration may be an important factor, it is not a decisive one, even in the most critical cases.”[xxxvii] Further, evidence shows that emigration of skilled workers in the health profession is not responsible for poor health outcomes in low-income countries.[xxxviii] Where ‘brain drain’ has occurred, it has resulted in a number of benefits for sending countries, such as remittances, wage gains, and knowledge transfer.[xxxix] Former Prime Minister Manhoman Singh of India was quoted as saying. “Today we in India are experiencing the benefits of the reverse flow of income, investment and expertise from the global Indian diaspora. The problem of ‘brain drain’ has been converted happily into the opportunity of ‘brain gain.’”[xl]

The evidence shows more of a ‘brain gain’ than ‘brain drain.’ The ‘brain drain’ narrative assumes a ‘lump of labor’ in which there is a fixed number of workers and thus a worker moving from one country to another is by definition a loss to the former and a gain to the latter.[xli] Migration opportunities increase earning potential within specific sectors, which in turn increase the return to skilling in that sector. This creates demand for training in this sector, which results not only in the emergence of specialized schools and vocational training institutes, but incentivizes more people to train than actually migrate. As a result, countries which actively promote employment abroad in certain sectors have seen the number of workers trained for those sectors grow domestically. The most vivid example of this is with nurses in the Philippines: Abarcar and Theoharides[xlii] find that the migration of nurses increased the stock of nurses in the Philippines. Nursing enrollments increased so much that for every trained nurse who migrated, 10 additional nurses were licensed in the country.[xliii] They further found that the supply of (private) nursing programs expanded to accommodate the increased demand for nursing degrees. Many more Filipina nurses work in the Philippines today as a direct result of the government’s decision to actively pursue a managed migration strategy. Similarly, studies have shown that the opportunity from skilled emigration from Cape Verde[xliv] and Fiji[xlv] increased the number of university graduates living in these countries.

So why don’t sending countries more actively try to encourage workers to find jobs abroad?

While labor mobility is a powerful tool towards quality employment and poverty alleviation for sending countries, few have pursued it as a strategy to expand opportunity for their people. A few countries (such as the Philippines, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and Nepal) have actively worked to expand employment opportunities for their workers abroad, and to harness the benefits of remittances and returnee skills for development of their countries. However, these countries are the exception rather than the rule, with many more focusing on programming that encourages employment at home to discourage migration (though it is worth noting that these programs are often at the encouragement of donors and receiving countries). For example, prior to the Overseas Employment Proclamation of 2016, Ethiopia’s direct policy on labor migration was to promote local employment and deal with labor migration only to regulate it.[xlvi]Even the Overseas Employment Proclamation in its current form has such stringent requirements that it in practice serves to discourage rather than encourage labor mobility, though it is now in the process of being revised.[xlvii]

What explains this? We have already mentioned pressure coming from donors and receiving countries. However, much of this resistance to actively promoting labor mobility stems internally. Government officials in low-income countries often view promoting labor mobility as a way to a better life for their people as admitting failure of their own development. As a result, labor mobility is treated as an option of last resort, and something to be regulated rather than promoted. There are two fundamental flaws in this thinking:

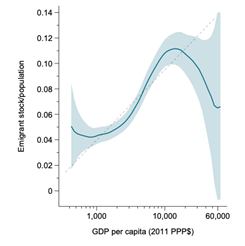

First, the belief that labor mobility signals a failure of development is rooted in the inaccurate belief that migration decreases with development. A commonly held belief is that migration reduces as incomes rise, implying that if governments in these countries were successful in their development efforts, their people would not seek to migrate. This belief is not supported by evidence, which instead has shown an ‘emigration life cycle’ in which migration first rises, then falls as GDP per capita increases in low-income countries. Figure 3a below shows the most recent estimates around this relationship; Clemens looks at all low- and middle-income countries between 1960 and 2019 and finds that migration increases with growth up to USD PPP 10,000 per capita GDP.[xlviii] The same research then looks at the relationship between changes in income and changes in the emigration rate within the same country over time (Figure 3b), and finds that as a country becomes ten times richer than it used to be, its average emigration rate rises by approximately five percentage points. These increasing emigration rates are a credit to improving development outcomes; as Clemens and Postel note, “as development proceeds, human capital accumulates, connections to international networks increase, fertility shifts, aspirations rise, and credit constraints are eased. All of these changes tend to raise emigration.”[xlix] We need a new narrative which recognizes that migration is often citizens of a country taking advantage of an expanded set of life options they are afforded by successful development.

Figure 3: Emigration rates increase as GDP per capita rises to middle-income

Source: Clemens 2020

Second, the success of governments is measured by the well-being of their country, rather than the well-being of their people. Measures of development are defined by what happens within a country’s borders; GDP or GNI per resident focus (and many other metrics of development) exclusively on the well-being of people currently residing in a given country. This is reinforced by the fact that development and aid programming are tied to these metrics, meaning that only activities whose impacts will be captured by these metrics are considered effective development programming. Pritchett and Clemens note that this “leads to untenable conclusions: if a Salvadoran moves from the countryside to San Salvador to get a factory job that raises her income 30%, this will be recorded as a welfare improvement for Salvadorans on average, but a 500% increase in income from a factory job in Texas does not.”[l] They go on to propose a new metric: income per natural, the mean per person income of those born in a given country, regardless of where they now reside. They find that the well-being of a country’s citizens looks vastly different when using this metric: Almost 43 million people lived in countries whose income per natural collectively is 50 percent higher than GDP per resident. For 1.1 billion people the difference exceeded 10 percent, and the numbers living under the poverty line were also vastly different using this approach.[li] If countries are committed to the well-being of their people, rather than well-being within their geographic territory, they should consider labor mobility a viable and positive strategy.

Beyond an ethos among sending countries that labor mobility reflects a failure on their part, there are specific concerns that prevent them from promoting labor mobility. A key concern is the risk of worker abuse and violations of their rights. This has concretely manifested as a political and reputational risk in sending countries, where cases of worker abuse have had direct and strong repercussions for government officials. Many times, cases of worker abuse have resulted in a complete ban from the sending country on recruitment of workers to a particular receiving country. For example, in 2018 Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte permanently banned Filipinos from working in Kuwait following the emergence of several cases of murder and abuse.[lii] Similarly, from 2013 to 2018, Ethiopia banned its workers from seeking employment in the Middle East and it has only recently begun exploring options to enhance labor mobility rather than shut it down,[liii] while the Government of Kenya also banned recruitment for overseas employment from 2014 to 2016 while it reportedly weighed labor mobility as a way to provide job opportunities and increase remittances against the “bad publicity” towards the Government from examples of worker abuse.[liv] India,[lv]Nepal,[lvi] and Bangladesh[lvii]have all instituted similar bans in the past. These bans have largely served only to encourage even more risky irregular migration; for example, within two years of Ethiopia banning labor mobility to the UAE, as many as 30,000 Ethiopians were detained there for irregular migration.[lviii] As noted before, concerns around ‘brain drain’ are another reason low-income countries choose to not pursue labor mobility as an employment strategy, though the experience of the Philippines and other countries shows that they could gain skilled workers by doing so.

How can sending countries pursue labor mobility as a jobs strategy?

Even where sending countries are committed to pursuing labor mobility as an employment strategy, there remain a number of complex challenges to do so. In order to promote managed labor mobility, sending countries need (1) a labor supply which matches the labor demand in high-income countries; (2) a legal framework establishing the right to work in another country and defining all the associated terms created in coordination with the receiving country; and (3) an effective and efficient infrastructure implementing this framework, through which workers are connected and moved to safe jobs abroad. Each of these three requirements represent significant challenges in the status quo.

First, there is a broad mismatch between the labor supply in low-income countries and labor demand in high-income countries. Labor shortages in high-income countries are predominantly in occupations requiring specific skill sets.[lix] At the same time, the labor supply in low-income countries with growing youth populations currently does not have the requisite education or skill sets to fill these positions. The OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) shows that the majority of workers in low-income countries have low literacy and skill levels, significantly below those of workers in OECD countries where the labor shortages are.[lx] To some extent this can create complementarities; however, this at least in part presents a skills mismatch acting as a barrier to labor mobility. Given the global labor shortages of skilled workers in specific professions, high- and low-income countries will need to work together in mutually beneficial ways to address these skills mismatches.

One example of this is Global Skills Partnerships (GSP), which bundles training for migrants with training for non-migrants in the origin country and connects training programs to a legal framework for migration.[lxi] The GSP model has been piloted through the ‘Pilot Project Addressing Labour Shortages Through Innovative Labour Migration Models’ (PALIM) which links Moroccan ICT development and labor shortages in Flanders.[lxii] The team running PALIM notes that a difficulty they experienced early on in the design of the project was in identifying and matching labor market needs in Belgium and Morocco. Beyond the challenges identified above, this also resulted from the poor available labor market data, particularly in the sending country.[lxiii]

Second, sending countries have little bargaining power in establishing a favorable legal framework for labor mobility with receiving countries. Negotiations around labor mobility are historically conducted behind closed doors, with little information made public, and are driven by personal networks of officials.[lxiv][5] Sending country officials with mandates to open new foreign labor markets for the country’s workers, report the primary constraint to be knowing which countries to approach and, within those countries, which official to approach and how. Beyond this, receiving countries hold significantly more bargaining power, as supply of foreign workers is much greater than demand to admit them in receiving countries, and sending countries often compete with each other for labor market access. This results in a ‘race to the bottom’ of sending countries lowering standards in order to be more competitive, while receiving countries take unilateral action. This results in a negative equilibrium where there is downward pressure on labor standards, while unilateral action leads to fragmented migration processes without transparency and accountability across borders. A Nigerian official noted that they have significant difficulties getting receiving countries to sign bilateral labor agreements (BLAs) and memorandums of understanding (MoUs), without with it is very challenging to protect the rights of their workers abroad.[lxv] This may change in the COVID-19 era, as receiving countries are more dependent on partnership with actors in sending countries to ensure workers are arriving COVID-19 free.[lxvi]

Third, sending countries have not built the capacity for efficient and effective implementing infrastructure, and there is little quality industry support. Excessive time and cost burdens of migration incentivize irregular migration and can undermine labor mobility if employers are not able to receive workers in a timely fashion. Therefore, the processes through which workers are matched with a job, screened for necessary clearances, and receive visa approval must be efficient, affordable, and convenient for applicants and employing sectors. Even more importantly, these systems must have the trust of the receiving country government and employers that the workers they receive are qualified for the jobs they are expected to perform, have been screened, and will abide by the conditions of their visa.[lxvii] This issue has become increasingly important in the COVID-19 era when receiving countries need to place significant trust in the health screening processes of sending countries; examples of fraud in these systems have already had important impacts.[lxviii]

Even before COVID-19, receiving countries have expressed concern that capacity within sending country migration management systems prevented them from building more labor mobility partnerships.[lxix] One solution would be rather than building capacity within government to rely on a mobility industry to deliver services required throughout the migration process. However, mobility industry services are currently low-quality, resulting in bad outcomes for migrant workers.[lxx] Sending and receiving governments, employing sectors, and worker representatives should work together to (1) streamline and strengthen necessary government processes and 2) facilitate the emergence of a quality mobility industry. This will be examined further in a forthcoming LaMP note.

Conclusion

Sending country governments have good reason to engage in labor mobility partnerships. Bridging their labor surpluses with significant labor shortages in high-income countries alleviates risky employment pressures from their growing youth populations. Meanwhile, they stand to benefit from increased inflow of remittances and skill accumulation, both of which are powerful forces for bettering living standards in sending countries. Labor mobility should be held up as a success of sending governments to open opportunities for their people, rather than a failure of development. However, there are a number of challenges undermining the ability of sending country governments to facilitate employment opportunities abroad for their workers. These challenges are best solved in partnership, with receiving country governments, employers, and a quality mobility industry.

About LaMP

Labor Mobility Partnerships (LaMP) aims to increase rights-respecting labor mobility, ensuring workers can access employment opportunities abroad. Its overarching goal is to make it easier for its partners to build labor mobility systems at the needed scale, thus unlocking billions in income gains t people filling the needed jobs. It focuses on connecting governments, employers and sectors, the mobility industry, and researchers and advocates to bridge gaps in international labor markets, and creating and curating a repository of knowledge and resources to design and implement mobility partnerships which benefit all involved. LaMP’s functions include brokering relationships between potential partners, providing technical support from design to implementation of partnerships, and research and advocacy around the impacts of successful partnerships.

[1] It is important to note that job creation is very difficult to accurately project; as such, these figures should be taken only to make the broader point that there will be a large population of new working age people needing employment solutions.

[2] The dot-com bubble in the US was a stock market bubble caused by excessive speculation in Internet-related companies in the late 1990s, a period of massive growth in the use and adoption of the Internet. Indian and Chinese-born software engineers were heavily represented in the workforce of these companies. When the bubble burst, large numbers of these Indian- and Chinese-born software engineers returned to their respective countries, in part due to an inability to extend their work visas and in part because there were better employment opportunities in their home countries (Debnath 2016).

[3] Docquier and Marfouk (2005) define a country’s brain drain rate for a particular educational level as the share of all individuals with that education level aged 25 and over born in that country who live abroad.

[4] In this case, the term ‘skilled workers’ is used to refer to workers who are trained and have the necessary qualifications for specific occupations (such as health workers).

[5] Ibid.

[i] UN DESA (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs), Population Division. (2015). “World Population Prospects: The 2015 Revision.” DVD edition. 2015. New York: United Nations.

[ii] Smith, Rebekah and Hani, Farah. “Labor Mobility Partnerships: Expanding Opportunity with a Globally Mobile Workforce.” Center for Global Development. June 26, 2020. https://www.cgdev.org/publication/labor-mobility-partnerships-expanding-opportunity-globally-mobile-workforce

[iii] World Economic Forum. “The Africa Competitiveness Report 2017.” World Bank Group. 2017. http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/733321493793700840/pdf/114750-2-5-2017-15-48-23-ACRfinal.pdf

[iv] Osmani, S. R., 2006, “Employment Intensity of Asian Manufacturing: An Examination of Recent Trends”, Paper prepared for the Asian Regional Bureau of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), New York, March.

[v] Rodrik, Dani. “Premature Deindustrialization.” 2016. Journal of Economic Growth. 21(1). 2016. https://econpapers.repec.org/article/kapjecgro/v_3a21_3ay_3a2016_3ai_3a1_3ad_3a10.1007_5fs10887-015-9122-3.htm

[vi]Sanford, Mark and Mullen, Paul. “Health Consequences of Youth Unemployment.” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 19:4. 1985. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00048678509158851?journalCode=ianp20

[vii] McQuaid, Ronald. “Youth unemployment produces multiple scarring effects.” London School of Economics Blog. February 18th, 2017. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2017/02/18/youth-unemployment-scarring-effects/

[viii] Mroz, Thomas and Savage, Timothy. “The Long-Term Effects of Youth Unemployment.” Journal of Human Resources. 41(2). 2006. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40057276?seq=1

[ix] Urdal, Henrik. “A Clash of Generations? Youth Bulges and Political Violence.” International Studies Quarterly. 50(3). September 2006. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4092795

[x] Global Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development. “Remittances.” World Bank Group. 2018. https://www.knomad.org/data/remittances

[xi] Global Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development. “Migration and Development Brief 31.” World Bank Group. April 2019. https://www.knomad.org/publication/migration-and-development-brief-31

[xii] DeParle, Jason. “A Good Provider is One Who Leaves: One Family and Migration in the 21st Century.” Penguin Books. 2019.

[xiii] Ahmed, Junaid and Mughal, Mazhar. “How Do Migrant Remittances Affect Household Consumption Patterns?” January 30, 2015. SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2558094or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2558094

[xiv] Adams, Richard, and John Page. “Do International Migration and Remittances Reduce Poverty in Developing Countries?” World Development 33(10). 2005.

[xv] DeParle 2019.

[xvi] DeParle 2019.

[xvii] DeParle 2019

[xviii] Holzmann, Robert. “Managed Labor Migration in Afghanistan: Exploring Employment and Growth Opportunities for Afghanistan.” World Bank Group. 2018. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/29275

[xix] Ibid.

[xx] Yang, Dean C and Martinez, Claudia, “Remittances and Poverty in Migrants’ Home Areas: Evidence from the Philippines,” International Migration, Remittances, and the Brain Drain, 2006.

[xxi] Yang, Dean. “Why Do Immigrants Return To Poor Countries? Evidence From Philippine Migrants’ Responses To Exchange Rate Shocks,” Review of Economics and Statistics, 2006, v88(4,Nov), 715-735.

[xxii] Holzmann 2018.

[xxiii] Antón, José-Ignacio. “The Impact of Remittances on Nutritional Status of Children in Ecuador.” The International Migration Review. 44(2). Summer 2010. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25740850?seq=1

[xxiv] Amuedo-Dorantes, Catalina and Pozo, Susan. “New Evidence on the Role of Remittances on Health Care Expenditures by Mexican Households.” IZA Discussion Paper No. 4617. December 2009. http://ftp.iza.org/dp4617.pdf

[xxv] Acosta, P. “Labor Supply, School Attendance, and Remittances from International Migration: The Case of El Salvador.” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 3903. 2006. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

[xxvi]Chauvet, Lisa, Gubert, Flore & Mesplé-Somps, Sandrine. “Aid, Remittances, Medical Brain Drain and Child Mortality: Evidence Using Inter and Intra-Country Data.” The Journal of Development Studies, 49:6. 2013. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00220388.2012.742508?journalCode=fjds20

[xxvii] De, Supriyo et al. “Remittances over the Business Cycle: Theory and Evidence. Global Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development. World Bank Group. March 2016. https://www.knomad.org/sites/default/files/2017-07/KNOMAD%20WP%2011%20Remittances%20over%20the%20Business%20Cycle.pdf

[xxviii] Wahba, Jackline. “Return migration and economic development.” Chapters, in: Robert E.B. Lucas (ed.),International Handbook on Migration and Economic Development, chapter 12. 2014. Edward Elgar Publishing.

[xxix] Debnath, Priyanka. “Leveraging Return Migration for Development: The Role of Countries of Origin.” Global Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development. World Bank Group. November 2016.

[xxx] DeParle 2019.

[xxxi] Labor Mobility Partnerships. “Workers on the Move: Labor Mobility as a Jobs Solution for Sending Countries.” Webinar. September 10, 2020. https://lampforum.org/what-we-do/research-and-advocacy/events/1382-2/

[xxxii] Dumont, J.-C., and G. Spielvogel. “Return Migration: A New Perspective.” In International

Migration Outlook, Part III. 2008. Paris: OECD Publishing.

[xxxiii] Giordano, A., and G. Terranova. 2012. “The Indian Policy of Skilled Migration: Brain Return versus

Diaspora Benefits.” Journal of Global Policy and Governance 1 (1): 17–28.

[xxxiv] Hausmann, Ricardo and Nedelkoska, Ljubica. “Welcome Home in a Crisis: Effects of Return Migration on the Non-migrants’ Wages and Employment.” European Economic Review. 2017.

[xxxv] Wasti, Satish. “The Myth of Brain Drain: How Emigration Can Help Poor Countries.” Harvard Political Review. 2018. https://harvardpolitics.com/world/the-myth-of-brain-drain-how-emigration-can-help-poor-countries/

[xxxvi] Gibson, John and McKenzie, David. “Eight Questions about Brain Drain.” Journal of Economic Perspectives. 25(3). Summer 2011. https://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/pdfplus/10.1257/jep.25.3.107

[xxxvii] OECD. “International Migration Outlook 2015.” OECD. September 22, 2015. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/international-migration-outlook-2015_migr_outlook-2015-en

[xxxviii] Clemens, Michael. “Do visas kill? Health effects of African health professional emigration.” Center for Global Development. Working Paper 114. March 2007. https://www.cgdev.org/publication/do-visas-kill-health-effects-african-health-professional-emigration-working-paper-114

[xxxix] Gibson, John and McKenzie, David John, The Economic Consequences Of “Brain Drain” Of the Best and Brightest: Microeconomic Evidence from Five Countries (August 1, 2010). World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 5394. https://ssrn.com/abstract=1653198

[xl] Government of India. “Hiren Mukherjee Memorial Lecture 2010 Parliament of India Prime Minister’s Remarks.” Prime Minister’s Office Press Release, December 2, 2010. http://pib.nic.in/release/release.asp?relid=68026.

[xlii] Abarcar, Paolo, and Theoharides, Caroline. “Medical Worker Migration and Origin-Country Human Capital: Evidence from U.S. Visa Policy.” Amherst College. July 2020. https://www.amherst.edu/system/files/Abarcar_Theoharides_2020_July_FINAL.pdf

[xliii] Ibid.

[xliv] Batista, Catia, Lacuesta, Aitor, and Vicente, Pedro. “Brain Drain or Brain Gain? Micro Evidence from an African Success Story.” IAE CSIC. September 10, 2007. http://www.iae.csic.es/investigatorsMaterial/a87315173392438.pdf

[xlv] Clemens, Michael and Chand, Satish. “Human Capital Investment under Exit Options: Evidence from a Natural Quasi-Experiment.” Center for Global Development Working Paper 152. September 2008 (Revised February 2019). https://www.cgdev.org/publication/human-capital-investment-under-exit-options-evidence-natural-quasi-experiment

[xlvi] International Labour Organization. “The Ethiopian overseas employment proclamation No. 923/2016: a comprehensive analysis.” ILO Country Office for Ethiopia, Djibouti, Somalia, Sudan and South Sudan. 2017a. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—africa/—ro-abidjan/documents/publication/wcms_554076.pdf

[xlvii] Labor Mobility Partnerships 2020.

[xlviii] Clemens, Michael. “The Emigration Life Cycle: How Development Shapes Emigration from Poor Countries.” Center for Global Development Working Paper 540. August 2020. https://www.cgdev.org/publication/emigration-life-cycle-how-development-shapes-emigration-poor-countries

[xlix] Ibid.

[l] Clemens, Michael and Pritchett, Lant. “Income per Natural: Measuring Development for People Rather Than Places.” Population and Development Review. September 2008. 34:3. Pp. 395-434.

[li] Ibid.

[lii] Turak, N. “Philippines’ Duterte Declares Permanent Ban on Workers Going to Kuwait after Abuse and Murder Cases.” CNBC, April 30, 2018. https://www.cnbc.com/2018/04/30/philippines-duterte-declares-permanent-ban-on-workers-going-to-kuwait.html.

[liii] Agence France-Presse. “Ethiopia Lifts Ban on Domestic Workers Moving Overseas.” Arab News, February 2, 2018. https://www.arabnews.com/node/1237981.

[liv] ILO. “The Migrant Recruitment Industry Profitability and unethical business practices in Nepal, Paraguay and Kenya.” International Labour Office, Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work Branch. 2017. Geneva.

[lv] Whiteman, H. “Indonesia Maid Ban Won’t Work in Mideast, Migrant Groups Say.” CNN, May 6, 2015. https://www.cnn.com/2015/05/06/asia/indonesia-migrant-worker-ban/index.html.

[lvi] Pyakurel, U. “Restrictive Labour Migration Policy on Nepalese Women and Consequences.” Sociology and Anthropology 6 (8): 650–656. 2018. http://www.hrpub.org/download/20180730/SA3-19611136.pdf.

[lvii] Shamim, I. “The Feminisation of Migration: Gender, the State and Migrant Strategies in Bangladesh.” In Kaur, A., and Metcalfe, I. (eds.), Mobility, Labour Migration and Border Controls in Asia. 2006. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

[lviii] Labor Mobility Partnerships 2020.

[lix] Cepla, Zuzana. “Why Labor Mobility? Labor Mobility Can Assist Employing Sectors with Addressing Growing Labor Scarcity.” Labor Mobility Partnerships. August 20, 2020. https://lampforum.org/what-we-do/research-and-advocacy/policy-notes/why-labor-mobility-2/

[lx] Smith and Hani 2020.

[lxi] Clemens, Michael and Gough, Kate. “A Tool to Implement the Global Compact for Migration: Ten Key Steps for Building Global Skill Partnerships.” Center for Global Development. December 4, 2018. https://www.cgdev.org/publication/tool-implement-global-compact-migration-ten-key-steps-building-global-skill-partnerships

[lxii] Enabel. “PALIM – European Pilot Project Linking Moroccan ICT Development And Labour Shortages In Flanders.” March 1, 2019. https://www.enabel.be/content/europees-proefproject-palim-linkt-it-ontwikkeling-marokko-aan-knelpuntberoepen-vlaanderen-0

[lxiii] Labor Mobility Partnerships 2020.

[lxiv] Malit, Froilan. “Frontlines of Global Migration: Philippine State Bureaucrats’ Role in Migration Diplomacy and Workers’ Welfare in the Gulf Countries.” Chapter in P. Fargues and N. M. Shah (eds.), Migration to the Gulf: Policies in Sending and Receiving Countries. Fiesole, Italy: EIU Gulf Labor Markets, Migration, and Population Programme. 2018. http://gulfmigration.org/media/pubs/book/grm2017book_chapter/Volume%20-%20Migration%20to%20Gulf%20-%20Chapter%2010.pdf.

[lxv] Labor Mobility Partnerships 2020.

[lxvi] Smith, Rebekah. “Labor Mobility in the Post-COVID-19 Era: The Case for Partnerships.” Labor Mobility Partnerships. July 28, 2020. https://lampforum.org/what-we-do/research-and-advocacy/policy-notes/labor-mobility-in-the-post-covid-19-era-the-case-for-partnerships/

[lxvii] Smith and Hani 2020.

[lxviii] Smith 2020.

[lxix] Smith and Hani 2020.

[lxx] Smith, Rebekah and Johnson, Richard. “Introducing an Outcomes-Based Migrant Welfare Fund.” Labor Mobility Partnerships. January 16, 2020. https://lampforum.org/2020/01/16/introducing-an-outcomes-based-migrant-welfare-fund/