Why Labor Mobility?

The ‘Why Labor Mobility?’ series of policy notes explores the historic need for labor mobility from the lens of key actors:

- receiving countries

- sending countries

- employers

- workers

- ‘mobility industry’

This second note in the series focuses on the perspective of employing sectors attempting to address growing labor scarcity.

Key Points

- Employing sectors in high-income countries have been facing unprecedented labor scarcity, weighing on employers’ productivity and viability, and thus overall growth, prosperity, and well-being of the nations.

- While automation may address some of the job scarcity, it cannot close all of the gaps as many of the needed positions are non-substitutable. Additionally, automation represents an economically inefficient solution that disadvantages certain native-born workers.

- Labor mobility offers the most feasible solution, allowing employing sectors as well as employers in high-income countries to at least partially close their labor gaps, while spurring innovation and bringing workers with various backgrounds to their workplace.

Introduction

High-income countries’ employing sectors[1] face unprecedented scarcity of native-born workers, especially with low and medium skills. As the nations’ populations get older as a consequence of declining fertility rates, their overall workforce shrinks, preventing employers across industries to find enough workers to fill the gaps. Although many call this trend “labor shortage,” this note refers to it as “labor scarcity” since the employing sectors in high-income countries are unable to address the issue simply by increasing wages as discussed below. While the COVID-19 pandemic has caused some temporary swings with closures of businesses and thousands of furloughed workers worldwide, this underlining long-term trend is unlikely to change. Without sufficient number of mobile workers with necessary skills, employing sectors will continue to struggle to produce and deliver often vital goods and services, or even stay open for business. This labor scarcity has been negatively affecting communities and weigh on the high-income countries’ economies. Labor mobility can serve as an effective policy tool to help employing sectors in those countries to at least partially close their deepening labor gaps.[2]

High-Income Countries Face Deepening Labor Gaps

In order to growth their economies and provide for prosperous societies, high-income countries need strong and booming employers. However, many employers in those countries have been experiencing ongoing hiring issues due to deepening gaps between their labor needs and available workforce. While this phenomenon, which occurs when the demand for workers for a particular occupation exceeds the supply of qualified and available individuals who are willing to take the position, is commonly-known as a ‘labor shortage’[i], we believe “labor scarcity” is a much more accurate term. Typically, economists define “shortage” as “a lack at a given price.” Therefore, common-sense solution to “shortages” is to allow prices to rise to match the supply and demand. However, in case of labor, this approach allows just for reallocation of workers from one employer to another, but not for creation of additional workers. Therefore, we chose to use term “labor scarcity.”

In recent years, job scarcity has weighed on productivity and viability of employers in high-income countries. The U.S. had nearly 7 million unfilled jobs – a record-high level[ii]– earlier in 2019, and the European Union has seen significant labor scarcity across all member countries as well.[iii] Germany, for example, reported about 1.6 million unfilled jobs in 2018[iv] and France saw some 200,000-330,000 job offers to go unfilled in 2017[v] (Table 1).

Table 1. Recent Total Job Scarcity Selected High-Income Countries

| Country | Total Job Scarcity | Year Reported |

| United States | 7 million | 2019 |

| Germany | 1.6 million | 2018 |

| France | 200,000-330,0000 | 2017 |

This trend is unlikely to stop anytime soon. Italy is expected to lack on average at least 100,000 workers across a variety of sectors per year,[vi] while in Poland, the scarcity is predicted to average 250,000 workers annually.[vii] Switzerland projects to have a scarcity of 500,000 workers by 2030, or approximately 50,000 each year from 2020 to then, which in total accounts for about 10 percent of the country’s total workforce.[viii] Additionally, Canada’s labor scarcity had been predicted to get close to an average of 120,000 per year.[ix] Similarly, Japan is projected to face a scarcity of approximately 535,000 workers on average each year[x] (Table 2). In general, companies are finding it particularly difficult to fill positions requiring lower and medium level skills.[xi]

Table 2. Projected Total Job Scarcity in Selected High-Income Countries

| Country | Total Projected Job Scarcity | Time Range | Annual growth of Job Scarcity |

| Japan | 6.44 million | 2018 – 2030 | 535,000 |

| Canada | 2 million | 2014 – 2031 | 120,000 |

| Poland | 1.5 million | 2019 – 2025 | 250,000 |

| Switzerland | 500,000 | 2020-2030 | 50,0000 |

| Italy | 300,000 | 2019 – 2021 | 100,000 |

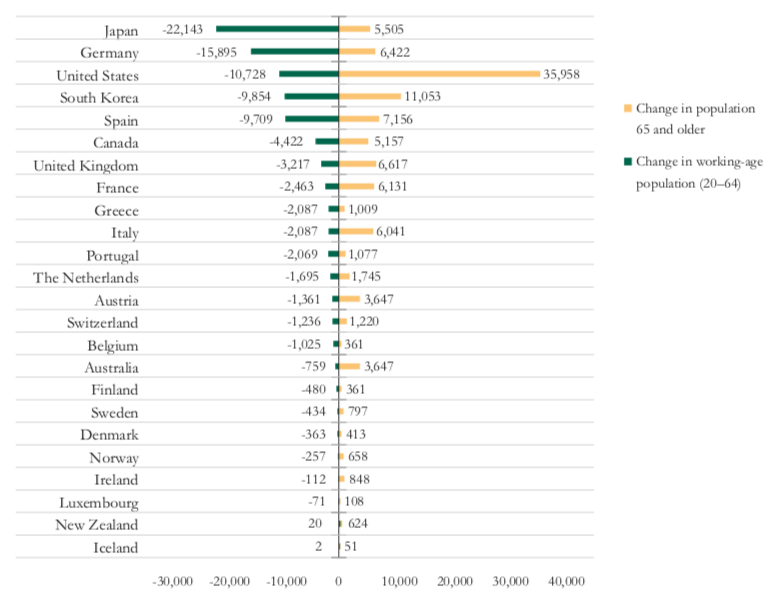

The lack of workers has been caused by previous, ongoing, and expected to continued demographic shifts in high-income counties. Specifically, aging population due to declining fertility rates has been the main cause of the deepening labor gaps. Based on the United Nations’ zero migration scenario, the working-age populations of countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)[5]will decline by more than 92 million by 2050, while their elderly populations (over 65 years old) are predicted to grow by more than 100 million people at the same time (Figure 1).[xii] Moreover, nations such as Germany, Japan, Italy and Spain have been experiencing continuous drops in numbers of newborn children since at least the 1970s, with fertility rates falling (in some cases deep) below the 2.1-level necessary for a population to replace itself.[xiii]Inevitably, the ongoing changes in demographic of the high-income countries will adversely affect the size of their workforce, which will continue to shrink in the upcoming years.

Figure 1. While the working-age population in most OECD countries declines, these countries are gaining elderly citizens.

A shrinking youth population and growing elderly population (in thousands)

Overall, the analysis of the ongoing demographic changes showed there will be a great need for more working-age individuals across sectors in virtually all the high-income countries. While the ongoing pandemic of COVID-19 has undoubtably shaken dynamics at the high-income countries’ labor markets, with many employers being forced to close their doors and furlough their staff. However, while unemployment rate and job openings are likely to stumble in the upcoming months, the long-term trend has remained unchanged. The high-income countries are simply unable to produce enough workers to be able to sustain their economies and structures of social protection.

Industry-Specific Labor Scarcity

Labor scarcity impacts each employer differently. As some of them try to address the issue by rising wages, this approach just “reallocates” workers creating shortages within sectors, rather than addressing the overall labor scarcity caused by demographic changes. While the labor gaps have been affecting employing sectors in virtually all of the high-income countries’ economies, many industries have been particularly hit. Among others, employers experience mismatch between the number of needed and available qualified workers in sectors such as care work, tourism, construction, manufacturing and agriculture. Although each of the high-income countries may struggle with job shortages in different sectors, virtually all of them have experienced labor scarcity in recent years.

Care Work

High-income countries have been facing deepening scarcity of care workers. Australia expects 250,300 job openings in this sector by 2023 and the U.S. even 7.8 million by 2026. The gaps in healthcare industry have been especially critical, since the increased number of elderly persons, resulting from the ongoing demographic shifts, will need adequate care. As people get older, they require more labor-intensive support – not only health care but also personal care and household help. Without sufficient number of workers in those sectors, the high-income countries will be unable to take appropriate care of the increasing numbers of elderly persons.[xiv]

Tourism

Tourism in some high-income countries has been also hampered by labor scarcity. In Germany, where tourism represents one of the key sectors, more than two-thirds of surveyed hoteliers and restaurateurs reported lack of workers as their top issue.[xv] These labor scarcities will result in shifting of work from workers to the travelers, who will either be asked to do the work themselves or it will not be done at all..[xvi]

Construction

However, other sectors face deepening workforce gaps as well. For instance, the construction sector in many rich nations has been lacking workers. The U.S. reported 434,000 vacant construction jobs in 2019,[xvii] while Germany saw approximately 225,000 unfilled position in this sector in 2018.[xviii] Similarly, U.S. construction companies are expected to be short of 747,000 workers by 2026,[xix] and the UK is predicted to need 200,000 construction workers already by the end of 2020.[xx] The situation has forced some construction firms to start asking more skilled workers to step in, increase prices or reject new projects as they struggle to meet deadlines.[xxi]

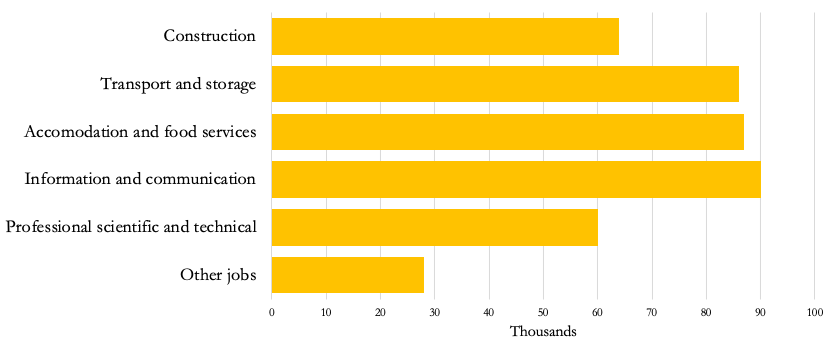

Figure 2. Changes in the number of jobs in the UK between December 2017 and December 2018, seasonally adjusted

Agriculture

Further, the agriculture sector has been facing deepening job scarcity as well, which weighs on the companies’ ability to produce food and could eventually result in broader food scarcity in the impacted high-income countries. In 2017, the Canadian agriculture reported a farmworker deficit of 16,500 – a number that is expected to double by 2029.[xxii] Australian[xxiii] and U.S.[xxiv] agriculture sectors have been stressing the need for more workers as well.

How Can Employers Address Labor Scarcity?

In effort to stay in business, employers have just a few available strategies to offset the existing scarcity of workers. As mentioned above, rising wages, which is typically the common-sense solution, just “reallocates” workers from one employer to another rather than fixing the overall labor scarcity. In other words, the industry overall cannot use this strategy as a solution to its lack of workers. No matter how much employers rise the wages, it simply doesn’t solve the problem. In Australia, nearly 75 percent of surveyed farmers offer above-average wages, and yet two thirds of them ranked labor concerns among the top three challenges they predict to face in the future.[xxv] Historical evidence also reveals this tendency. In the U.S. in 1960s, after termination of the Bracero Program[6], the U.S. growers were unable to recruit native-born agricultural workers, who would take the jobs formerly performed by the foreign workers, despite the many years of state and federal hiring efforts before and after closure of the program.[xxvi]

Additionally, some employers try to bridge their labor gaps by using other tools aimed at mobilization of their native-born workforce. In Slovakia, certain employers pledge to hire employees’ spouses. A Polish company has been reportedly using prisoners to boost its workforce[xxvii], as well as many companies in the U.S where they are paid very close to nothing or even work without any pay at all.[xxviii] Others provide incentives such as cash rewards for employees who help find new workers,[xxix] in addition to longer holidays, shorter hours and flexible shifts.[xxx] However, this approach again doesn’t address the labor scarcity caused by demographic changes in high-income countries.

Therefore, many employers decided to invest money into automation and digitalization to deal with the growing job scarcity. A recent report showed German employers have about 338 robots per 10,000 workers, and Central European countries such as Czech Republic, Hungary or Poland have been increasing their robot-to-workers ratios as well.[xxxi] In 2017, estimated 9,900 robots were installed in Central and Eastern Europe alone, which was 28 percent more than in the preceding year. However, not all employers facing job scarcity can rely on automation, since the process requires highly skilled workers experienced with programming, maintenance and servicing of the new machines, who are hard to find. Additionally, many, especially small, employers simply cannot afford to automate.[xxxii]

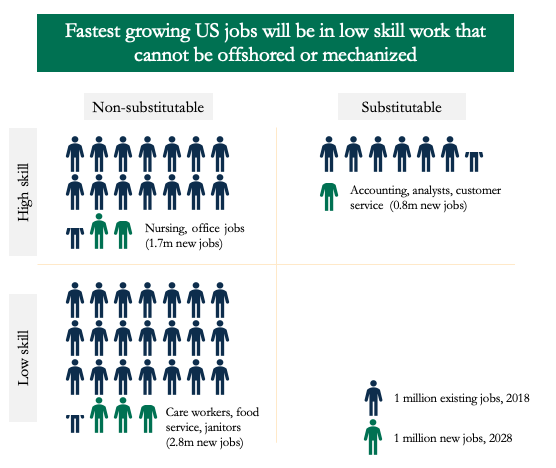

And last but surely not least, certain sectors cannot rely on automation because of the nature of the jobs they need. For instance, while U.S. construction companies have been exploring the potential of robotics, many jobs in this sector cannot be automated due to their overall complexity.[xxxiii] Similarly, professions such as nurses, care workers, janitors simply cannot be substituted by machines. In the U.S., for example, the economy was predicted to need 1.7 million high- and 2.8 million low-skill jobs that cannot be outsourced or mechanized by 2028 (Figure 3). Moreover, a recent study focusing on U.S. dairy industry showed that in the short run, technological gains were insufficient to entirely offset negative shock to production resulting from a shift in labor supply.[xxxiv]

Figure 3. Substitutable[7] and Non-Substitutable Jobs in the U.S. (2018 vs 2028)

Overall, rather than addressing a true “scarcity”, automation attempts to solve “policy-induced” scarcity, and thus is economically inefficient. In the long run, it fails to benefit native-born workers with low skills, as it destroys jobs that, when paired with other labor, could have survived. There is no reason to choose machines over people, since there are many available workers around the globe. However, the goal of gathering capital makes many unwilling to unchain their imagination about how to address the social and political challenges preventing labor mobility. And yet, from labor scarcity perspective, labor mobility dominates among all the possible solutions addressing labor shortages in employing sectors.

Labor Mobility as a Solution to Job Scarcity in High-Income Countries

It is clear that while the options above may work for some, they are certainly not suitable for all employers in high-income countries. Therefore, many of them consider labor mobility to be one of the most effective tools to overcome the deepening labor scarcity. [xxxv] Overall, the International Organisation of Employers (IOE) found that “employers regard regular migration as a necessary and positive phenomenon.”[xxxvi] In Poland, many manufacturers have been hiring large numbers of employees from abroad to fill their job openings as they cannot afford to invest into automation.[xxxvii]

Besides filling vacancies and increased productivity, foreign workers bring also other advantages to their employers. For instance, hiring foreign workers increases employers’ access to international knowledge, which also supports upskilling of their native workers; strengthens the employers’ contacts in international markets as well as local networks through improved language skills and higher cultural awareness; and creates more diverse work environment with a variety of experiences and ways of working.[xxxviii] Also, employers appreciate dependability and reliability of foreign workers. Due to high turnover of native workers, to many foreign workers represent more stable workforce. A study of Pacific migrants in New Zealand found that employers appreciate dependability and enthusiasm of the foreign workers, and that the effects of having reliable workforce were “reduced recruitment and training costs, increased confidence to expand and invest, and reduced stress.”[xxxix] Moreover, another recent study showed that hiring high-skilled foreign workers brings more innovation than spending money on research and development.[xl]

However, inefficient legal pathways and labor mobility programs for foreign workers often prevent employing sectors from filling their labor gaps. This inefficiency has been reflected in a variety of ways. First, political maneuvering leads to lack of transparency and predictability, which makes it more difficult for employers to make effective workforce decisions. For example, the Trump administration has made nearly 50 changes into the U.S. migration system just since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.[xli] Such abrupt and constantly changing environment has been negatively affecting every-day work and spurring uncertainty among the country’s employers as well as foreign workers.[xlii]

Second, the cost of compliance is simply too high for many especially small employers. Poorly designed labor mobility systems create burdensome regulatory requirements for employers, in some cases making it all but impossible for them to hire foreign workers. The Federation of Egyptian Industries reported that out of the 60,000 mostly small- and mid-size businesses, more than 95% have insufficient human resources structures to hire experts that would assist them with explanations of rules and policies related to hiring foreign workers – an issue that would be at least somewhat avoided with more transparency and clarity of the regulations mentioned above.[xliii]

Third, the negative perceptions and narratives around labor mobility create political and reputational risks which constrain policy makers and employing sectors from working together to build needed labor pathways. Currently, foreign workers are perceived by many in high-income countries in a negative way[xliv] despite the positive contributions they make to their social security systems.[xlv] Additionally, due to the negative migration narratives, employing sectors often face a backlash for hiring foreign workers, impacting their reputation and preventing them from more actively pushing for labor pathways.

Four, inadequate systems of skills and certification transfers also prevent many employers from hiring foreign workers, many of whom may have the needed qualifications but are unable to use them in the destination country.[xlvi]

Concerned that labor mobility policies are more often used to gain political points than fulfilling economic need of the involved employers, workers, and countries overall,[xlvii] employing sectors in a number of high-income countries have pressed their governments to design mobility systems which are responsive to labor market needs. For example, during the past decade, U.S. manufacturers[xlviii] and representatives of the agriculture sector[xlix] have been advocating for changes in the country’s immigration system. Their concerns go beyond levels of foreign workers, to the need for well-regulated movement of the individuals through rules mitigating risks that come with such mobility.

It is in the governments’ interest to listen to these calls as the countries’ economies rely on viability of their employers. In the recent years, inability to hire sufficient number of qualified workers has been weighing on employers’ productivity, and in many cases represents an existential threat to the impacted entities.[l] Subsequently, this reality has inevitably a broader adverse effect on economies of the high-income countries. For example, some experts worry that Germany could see an economic slowdown in the upcoming years. A recent survey showed that one out of every two German companies surveyed is unable to find qualified candidates to fill its openings over a long period of time, and six out of ten managers consider the situation to be threatening to their business.[li] Similarly, analysts expect slowdowns in economic growth rates among Eastern European countries in the upcoming two or three years, naming severe labor scarcity as one of the main factors contributing to this trend.[lii] Japan’s economic growth rate had been expected to fall to about 0.1 percent during 2026 and 2030, unless the country addresses the ongoing labor scarcity,[liii] and the forecast for the U.S. economy seems to be sluggish as well.[liv]

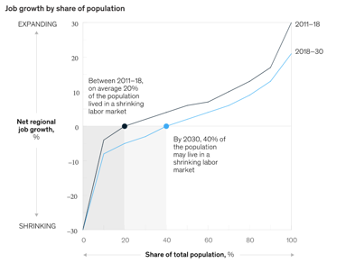

Additionally, a recent report found that by 2030, as many as 40 percent of Europeans may live in regions with shrinking labor markets, heightening the importance of labor mobility even more. According to the estimates, existing residents in many large cities will be able to fill less than 60 percent of the projected job growth. Besides remote work, commuting and physical moves, the employers will have to hire foreign workers to fill the remaining openings.[lv]

Figure 4. By 2030, As Many As 40 Percent of Europeans May Live in Regions With Shrinking Labor Markets[8]

Recognizing the need for labor mobility, some of the high-income countries’ governments have started to implement policies to support employing sectors’ efforts to hire foreign workers. Germany has prepared a plan in 2019 to speed up the visa process and make it easier for employers to recognize foreign qualifications and credentials.[lvi] Croatia’s strategy is to allow more foreign workers from outside of the European Union into the country, raising its quota by about 35,000 in 2020.[lvii] Even Japan, the most homogenous among OECD countries, had announced launch of a pilot program in 2018 to bring in more than 300,000 workers over the following five years to fight labor scarcity. In Australia, migration has played a major role in the last almost three decades of country’s economic expansion. Over the last couple of years, Australian real economic growth hovered around solid 2 to 2.5 percent, out of which nearly one percent was a result of migration.[lviii] At the end of 2019, the country’s government even forecast a budget surplus for fiscal year 2020, attributable to an assumption of high net migration.[lix]

It is clear that labor mobility programs allowing for flexible movement of a sufficient number of foreign workers represent the most feasible option for many employing sectors in the high-income countries. Labor mobility allows employers within these employing sectors to not only at least partially fill their labor scarcity, but also take advantage of many other benefits stemming from hiring of foreign workers. Overall, although labor mobility may force governments to respond to some political, economic and social concerns, evidence shows that in the long run, it fuels economic growth, and makes positive net contributions to the economies and societies in which the foreign workers live and work.[lx]

Conclusion

Employing sectors across virtually all high-income countries have been facing unprecedented labor scarcity, which have been reflected in their productivity and viability. Since many employing sectors have been facing these gaps for years, it is unlikely that the COVID-19 crisis will eliminate this trend. Despite the likely short-term rise of unemployment rates due to the pandemic, employers will still need what they have always needed: a mobile labor force that is well regulated to reduce risks that come with movement of people. Labor mobility offers the most feasible solution, allowing employing sectors to at least partially close their labor force gaps, while spurring innovation and bring workers with various background to their workplace.

Overall, employers consider well-managed labor mobility “a vehicle for fulfilling personal aspirations, for balancing labour supply and demand, for sparking innovation, and for transferring and spreading skills.”[lxi] Since economies of high-income countries depend heavily on performance of their employers, it is in the governments’ interest to act. The issue is already pressing and will become even more so over time. It is time for employing sectors, government, and mobility industry in high-income countries to connect, and together develop labor mobility systems, enabling foreign workers to enhance productivity, and overall prosperity of the affected nations.

About LaMP

Labor Mobility Partnerships (LaMP) aims to increase rights-respecting labor mobility, ensuring workers can access employment opportunities abroad. Its overarching goal is to make it easier for its partners to build labor mobility systems at the needed scale, thus unlocking billions in income gains to people filling the needed jobs. It focuses on connecting governments, employers and sectors, the mobility industry, and researchers and advocates to bridge gaps in international labor markets, and creating and curating a repository of knowledge and resources to design and implement mobility partnerships which benefit all involved. LaMP’s functions include brokering relationships between potential partners, providing technical support from design to implementation of partnerships, and research and advocacy around the impacts of successful partnerships.

[1] For the purpose of this note, “employing sectors” have been defined as employer associations and other organizations as well as employers themselves representing a variety of industries

[2] Developed countries with key labor scarcity are referred to as high-income countries.

[3] Glassman, Jim. “Help Wanted: Why the US Has Millions of Unfilled Jobs.” JP Morgan, January 29, 2020. https://www.jpmorgan.com/commercial-banking/insights/why-us-has-millions-of-unfilled-jobs.

Nienaber, Michael. “Labor Shortages May Undermine German Economic Boom: DIHK Survey.” Thomson Reuters, March 13, 2018. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-germany-economy-labour/labor-shortages-may-undermine-german-economic-boom-dihk-survey-idUSKCN1GP109.

“France’s New Labour Problem-Skills Shortages.” The Economist, March 8, 2018. https://www.economist.com/europe/2018/03/08/frances-new-labour-problem-skills-shortages.

[4] “Worker Shortage in Japan to Hit 6.4m by 2030, Survey Finds.” Nikkei Asian Review, October 25, 2018. https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Japan-immigration/Worker-shortage-in-Japan-to-hit-6.4m-by-2030-survey-finds2.

Miner, Rick. Rep. The Great Canadian Skills Mismatch: People Without Jobs, Jobs Without People and More, March 2014. https://www.wpboard.ca/hypfiles/uploads/2017/05/Miner_March_2014.pdf.

Wilczek, Maria. “Poland Struggles to Find Workers as Unemployment Hits 28-Year Low.” Al Jazeera, August 29, 2019. https://www.aljazeera.com/ajimpact/poland-struggles-find-workers-unemployment-hits-28-year-190829195115010.html.

“More Jobs – but Are There Enough Workers?” UBS, July 11, 2019. https://www.ubs.com/global/en/media/display-page-ndp/en-20190711-outlook-3q19.html.

“These Are the Thousands of Job Vacancies That Italy Can’t Fill.” The Local, February 18, 2019. https://www.thelocal.it/20190218/these-are-the-thousands-of-job-vacancies-that-italy-cant-fill.

[5] Data used for this note considered the following OECD countries: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United States, and the United Kingdom.

[6] The Bracero Program was set of three bilateral agreements between the United States and Mexico to regulate the flows of temporary low-skill labor between the two countries, spanning almost the entire period from 1942 through 1964.

[7] Substitutable jobs are jobs which can be automated or out-sourced. Non-substitutable jobs are jobs which must be performed in a given location and must be performed by a worker.

[8] The analysis focused on EU-27 countries plus United Kingdom and Switzerland; analysis of long-term labor market trends and impact of automation was conducted before COVID-19 pandemic.

[i] Veneri, Carolyn M. Rep. Can Occupational Labor Shortages Be Identified Using Available Data? Bureau of Labor Statistics, March 1999. https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/1999/03/art2full.pdf.

[ii] Glassman, Jim. “Help Wanted: Why the US Has Millions of Unfilled Jobs.” JP Morgan, January 29, 2020. https://www.jpmorgan.com/commercial-banking/insights/why-us-has-millions-of-unfilled-jobs.

[iii] Rep. Determining Labour Shortages and the Need for Labour Migration from Third Countries in the EU. European Migration NEtwork, 2015. https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/what-we-do/networks/european_migration_network/reports/docs/emn-studies/emn_labour_shortages_synthesis__final.pdf.

[iv] Nienaber, Michael. “Labor Shortages May Undermine German Economic Boom: DIHK Survey.” Thomson Reuters, March 13, 2018. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-germany-economy-labour/labor-shortages-may-undermine-german-economic-boom-dihk-survey-idUSKCN1GP109.

[v] “France’s New Labour Problem-Skills Shortages.” The Economist, March 8, 2018. https://www.economist.com/europe/2018/03/08/frances-new-labour-problem-skills-shortages.

[vi] “These Are the Thousands of Job Vacancies That Italy Can’t Fill.” The Local, February 18, 2019. https://www.thelocal.it/20190218/these-are-the-thousands-of-job-vacancies-that-italy-cant-fill.

[vii] Wilczek, Maria. “Poland Struggles to Find Workers as Unemployment Hits 28-Year Low.” Al Jazeera, August 29, 2019. https://www.aljazeera.com/ajimpact/poland-struggles-find-workers-unemployment-hits-28-year-190829195115010.html.

[viii] “More Jobs – but Are There Enough Workers?” UBS, July 11, 2019. https://www.ubs.com/global/en/media/display-page-ndp/en-20190711-outlook-3q19.html.

[ix] Miner, Rick. Rep. The Great Canadian Skills Mismatch: People Without Jobs, Jobs Without People and More, March 2014. https://www.wpboard.ca/hypfiles/uploads/2017/05/Miner_March_2014.pdf.

[x] “Worker Shortage in Japan to Hit 6.4m by 2030, Survey Finds.” Nikkei Asian Review, October 25, 2018. https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Japan-immigration/Worker-shortage-in-Japan-to-hit-6.4m-by-2030-survey-finds2.

[xi] https://www.beroeinc.com/whitepaper/talent-migration-solution-labour-shortage-europe/

[xii] Smith, Rebekah, and Farah Hani. “Labor Mobility Partnerships: Expanding Opportunity with a Globally Mobile Workforce.” Center For Global Development, June 26, 2020. https://www.cgdev.org/publication/labor-mobility-partnerships-expanding-opportunity-globally-mobile-workforce.

[xiii] “Fertility Rate, Total (Births per Woman),” accessed June 2, 2020, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.TFRT.IN?end=2018.

[xiv] Lant Pritchett, “Only Migration Can Save the Welfare State,” Foreign Affairs, February 24, 2020, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/2020-02-24/only-migration-can-save-welfare-state.

[xv] Rogers, Iain. “Germany’s Tourism Success Story Threatened by Worker Shortage.” Skift, December 24, 2019. https://skift.com/2019/12/24/germanys-tourism-success-story-threatened-by-worker-shortage/.

[xvi] Lippo, Caralynn. “The Hospitality Industry Has More than 1 Million Unfilled Jobs across the US, and It’s Taking a Toll on Some of the Basic Hotel Amenities That Guests Expect.” Business Insider, September 13, 2019. https://www.businessinsider.com/hotel-industry-major-workforce-shortage-affects-amenities-2019-9.

[xvii] Cilia, Juliette. “The Construction Labor Shortage: Will Developers Deploy Robotics?,” July 31, 2019. https://www.forbes.com/sites/columbiabusinessschool/2019/07/31/the-construction-labor-shortage-will-developers-deploy-robotics/.

[xviii] Milovanovic, Vladimir. “Labour Shortage Set to Escalate Construction Costs in 2019.” 3lite, November 28, 2018. https://3lite.co/2018/11/28/labour-shortage-set-to-escalate-construction-costs-in-2019/.

[xix] De Lea, Brittany. “As Construction Worker Shortage Worsens, Industry Asks Government for Help.” Fox Business, August 27, 2019. https://www.foxbusiness.com/economy/construction-worker-shortage-worsening.

[xx] Sargent, Joe. “Tackling the UK Construction Skills Shortage.” KHL, January 29, 2020. https://www.khl.com/construction-europe/tackling-the-uk-construction-skills-shortage/142170.article.

[xxi] “70% Of Contractors Struggling to Meet Deadlines as Labor Shortage Persists.” ContractorMag.com, March 14, 2019. https://www.contractormag.com/construction-data/article/20883834/70-of-contractors-struggling-to-meet-deadlines-as-labor-shortage-persists.

[xxii] Nosowitz, Dan. “Canada Has A Huge Agricultural Labor Shortage.” Modern Farmer, July 19, 2019. https://modernfarmer.com/2019/07/canada-has-a-huge-agricultural-labor-shortage/.

[xxiii] “4 Opportunities to Fix Australia’s Agriculture Labour Crisis.” Agricrew. Accessed July 7, 2020. https://www.agricrew.com.au/news/4-opportunities-to-fix-australia-s-agriculture-labour-crisis/45184/.

[xxiv] Duvall, Zippy. “Another Year of Farm Labor Shortages.” American Farm Bureau Federation – The Voice of Agriculture, July 10, 2019. https://www.fb.org/viewpoints/another-year-of-farm-labor-shortages.

[xxv] “4 Opportunities to Fix Australia’s Agriculture Labour Crisis.” Agricrew. Accessed July 7, 2020. https://www.agricrew.com.au/news/4-opportunities-to-fix-australia-s-agriculture-labour-crisis/45184/.

[xxvi] Clemens, Michael A., Ethan G. Lewis, and Hannah M. Postel. Rep. Immigration Restrictions As Active Labor Market Policy: Evidence From The Mexican Bracero Exclusion. National Bureau Of Economic Research, 2017. https://www.nber.org/papers/w23125.pdf.

[xxvii] Pandey, Ashutosh. “Labor Shortage Takes Steam out of Eastern Europe: DW: 29.03.2019.” DW.COM, March 29, 2019. https://www.dw.com/en/labor-shortage-takes-steam-out-of-eastern-europe/a-48116084.

[xxviii] McDowell, Robin, and Margie Mason. “Cheap Labor Means Prisons Still Turn a Profit, Even during a Pandemic.” Public Broadcasting Service, May 8, 2020. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/economy/cheap-labor-means-prisons-still-turn-a-profit-even-during-a-pandemic.

[xxix] Pandey, Ashutosh. “Labor Shortage Takes Steam out of Eastern Europe: DW: 29.03.2019.” DW.COM, March 29, 2019. https://www.dw.com/en/labor-shortage-takes-steam-out-of-eastern-europe/a-48116084.

[xxx] Thomasson, Emma. “Short on Workers, German Companies Offer More Employee Flexibility.” Thomson Reuters, June 27, 2018. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-world-work-germany/short-on-workers-german-companies-offer-more-employee-flexibility-idUSKBN1JN0H7.

[xxxi] Shotter, James. “Polish Companies Turn to Robots as Labour Shortage Bites.” Financial Times, December 17, 2019. https://www.ft.com/content/cd97b426-15e6-11ea-9ee4-11f260415385.

[xxxii] Szakacs, Gergely. “Enter the Robots: Automation Fills Gaps in East Europe’s Factories.” Thomson Reuters, February 7, 2018. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-easteurope-automation-insight/enter-the-robots-automation-fills-gaps-in-east-europes-factories-idUSKBN1FR1ZK.

[xxxiii] Cilia, Juliette. “The Construction Labor Shortage: Will Developers Deploy Robotics?,” July 31, 2019. https://www.forbes.com/sites/columbiabusinessschool/2019/07/31/the-construction-labor-shortage-will-developers-deploy-robotics/.

[xxxiv] Diane Charlton and Genti Kostandini, “Can Technology Compensate for a Labor Shortage? Effects of 287(g) Immigration Policies on the U.S. Dairy Industry” (American Journal of Agricultural Economics, August 12, 2020), https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/ajae.12125.

[xxxv] Shotter, James. “Polish Companies Turn to Robots as Labour Shortage Bites.” Financial Times, December 17, 2019. https://www.ft.com/content/cd97b426-15e6-11ea-9ee4-11f260415385.

[xxxvi] Rep. IOE Position Paper on Labour Migration. International Organisation of Employers, December 2018. https://www.ioe-emp.org/index.php?eID=dumpFile&t=f&f=135034&token=acb0ba361bca8f4ac7fa09eb0f5ad63d6c3c130f.

[xxxvii] Shotter, James. “Polish Companies Turn to Robots as Labour Shortage Bites.” Financial Times, December 17, 2019. https://www.ft.com/content/cd97b426-15e6-11ea-9ee4-11f260415385.

[xxxviii] “Advantages of Employing Migrant Workers.” nibusinessinfo.co.uk. Accessed July 7, 2020. https://www.nibusinessinfo.co.uk/content/advantages-employing-migrant-workers.

[xxxix] Curtain, Richard, Matthew Dornan, Jesse Doyle, and Stephen Howes. Rep. Labour Mobility: The Ten Billion Dollar Prize. Pacific Possible, July 2016. http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/555421468204932199/labour-mobility-pacific-possible.pdf.

[xl] Khanna, Gaurav, and Munseob Lee. “Hiring Highly Educated Immigrants Leads to More Innovation and Better Products.” The Conversation, September 26, 2018. https://theconversation.com/hiring-highly-educated-immigrants-leads-to-more-innovation-and-better-products-100087.

[xli] Zak, Danilo. “Immigration-Related Executive Actions During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” National Immigration Forum, July 21, 2020. https://immigrationforum.org/article/immigration-related-executive-actions-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/.

[xlii] Owen, Quinn. “Trump’s Threat of Total Immigration Ban Ignites Outrage, Confusion.” ABC News. ABC News Network, April 21, 2020. https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/trumps-threat-total-immigration-ban-ignites-outrage-confusion/story?id=70265156.

[xliii] Workers on the Move: How Can Labor Mobility Help Employers Address Job Gaps? Labor Mobility Partnerships (LaMP), 2020. https://lampforum.org/what-we-do/research-and-advocacy/events/1206-2/ .

[xliv] Ibid

[xlv] Ibid.

[xlvi] Ibid.

[xlvii] Ibid.

[xlviii] “As House Moves On DACA, NAM Reaffirms Support For Congressional Action.” National Association of Manufacturers, May 23, 2019. https://www.nam.org/as-house-moves-on-daca-nam-reaffirms-support-for-congressional-action-4985/?stream=policy-legal.

[xlix] “Over 300 Agriculture Groups Send Letter of Support for Farm Workforce Modernization Act.” Congressman Mario Diaz-Balart, November 18, 2019. https://mariodiazbalart.house.gov/media-center/press-releases/over-300-agriculture-groups-send-letter-of-support-for-farm-workforce.

[l] Marshall, Ryan. “Crabmeat Industry Hit Hard by Lack of Workers.” USA Today, May 4, 2018. https://www.usatoday.com/story/money/business/2018/05/04/crabmeat-producers-closing-due-lack-workers/582800002/.

[li] Nienaber, Michael. “Labor Shortages May Undermine German Economic Boom: DIHK Survey.” Thomson Reuters, March 13, 2018. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-germany-economy-labour/labor-shortages-may-undermine-german-economic-boom-dihk-survey-idUSKCN1GP109.

[lii] Pandey, Ashutosh. “Labor Shortage Takes Steam out of Eastern Europe.” DW.COM, March 29, 2019. https://www.dw.com/en/labor-shortage-takes-steam-out-of-eastern-europe/a-48116084.

[liii] “Japan’s Labor Shortage Imperils Economic Growth.” Nikkei Asian Review, April 22, 2017. https://asia.nikkei.com/Economy/Japan-s-labor-shortage-imperils-economic-growth.

[liv] Naroff, Joel L. “Growth Trap: The U.S. Economy Has the Jobs but Not the Workers to Fill Them.” The Philadelphia Inquirer, November 10, 2019. https://www.inquirer.com/economy/economy-growth-rate-jobs-employment-investment-20191110.html.

[lv] Smith, Sven, Tilman Tacke, Susan Lund, James Manyika, and Lea Thiel. “The Future of Work in Europe.” McKinsey Global Institute, June 10, 2020. https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/future-of-work/the-future-of-work-in-europe?sid=3090235f-cdc9-4199-9ecf-eb76de0ac069.

[lvi] “Germany Outlines Plan to Attract Skilled Migrant Workers: DW: 16.12.2019.” DW.com, December 16, 2019. https://www.dw.com/en/germany-outlines-plan-to-attract-skilled-migrant-workers/a-51701315.

[lvii] Ciobanu, Liliana. “Croatia Welcomes More Foreign Workers to Offset Labor Shortages.” China Global Television Network, November 23, 2019. https://newseu.cgtn.com/news/2019-11-23/Croatia-welcomes-more-foreign-workers-to-offset-labor-shortages-LPQsO1ikb6/index.html.

[lviii] Evan Young, “Coronavirus Has Halted Immigration to Australia and That Could Have Dire Consequences for Its Economic Recovery” (SBS News, April 1, 2020), https://www.sbs.com.au/news/coronavirus-has-halted-immigration-to-australia-and-that-could-have-dire-consequences-for-its-economic-recovery.

[lix] David Crowe, “Budget Surplus under Threat as Treasury Considers Coronavirus ‘Wildcard’,” The Sydney Morning Herald (The Sydney Morning Herald, February 17, 2020), https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/budget-surplus-under-threat-as-treasury-considers-coronavirus-wildcard-20200217-p541nf.html.

[lx] Rep. IOE Position Paper on Labour Migration . International Organisation of Employers, December 2018. https://www.ioe-emp.org/index.php?eID=dumpFile&t=f&f=135034&token=acb0ba361bca8f4ac7fa09eb0f5ad63d6c3c130f.

[lxi] Ibid.