Severe worker shortages continue to threaten the health care sector in OECD countries. Ongoing demographic shifts pose a double challenge to long-term care providers: as populations age, there will not only be more seniors in need of adequate care but also fewer working-age individuals to fill the jobs. As Dutch Health Minister Conny Helder put it, we may face a future in which “old people will have to rely more on themselves and less on professional caregivers.”

At the same time, there are many workers in developing countries willing to take on these jobs. The ongoing demographic shifts will inevitably lead to the need for workers from abroad to fill jobs in OECD countries. More and better labor mobility programs must inevitably be a part of any solution to the long-term care sector’s worker shortage issue. The time is ticking. It is up to the governments to take action and open more and better migration pathways for workers from abroad to fill the openings that employers desperately need.

The Growing Labor Scarcity

The recent strikes of U.S. nurses over understaffing and the resulting concerns about ability to provide patients with adequate care are just the latest drop in the bucket when it comes to health care worker shortages around the world. Other OECD countries, from the United Kingdom to Spain, Belgium and others, have been seeing similar trends in the sector for years. As a result, the lack of workers is not only actively undermining labor conditions for existing workers but also creating unsafe conditions for the patients.

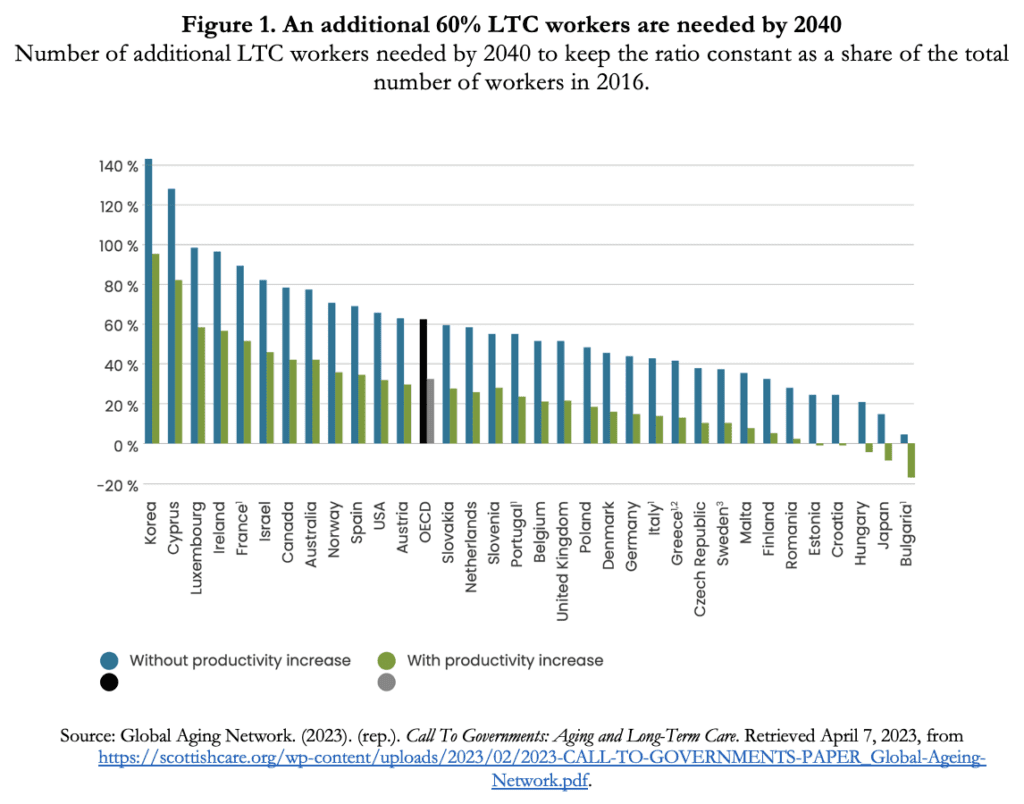

The long-term care (LTC) sector specifically faces the direst challenges. Latest estimates show that essentially all high-income countries, regardless of their demographics, are facing a crisis within their respective social care workforces. By 2040, the number of LTC workers in OECD countries will have to increase by 60 percent. In South Korea and Cyprus, providers will have to find ways to hire over 120 percent more workers given current levels of productivity.

In an effort to put pressure on their countries’ policymakers, representatives from the LTC sector issued a joint call to action earlier this year, urging policymakers to find solutions to the problem of worker shortages. Published by the Global Aging Network (GAN), an organization representing a wide variety of LTC stakeholders, the call stressed various workforce issues, including sustainable funding systems within the LTC sector, recruitment and retention of staff, and training of employees.

Aside from the lack of workers, the LTC providers have also faced the other result of aging within the OECD societies – the increased need for their services. In 2019, there were 703 million people older than 65 years in the world. Projections suggest the number will double to 1.5 billion in 2050 — one in six people around world will be at least 65 years old.

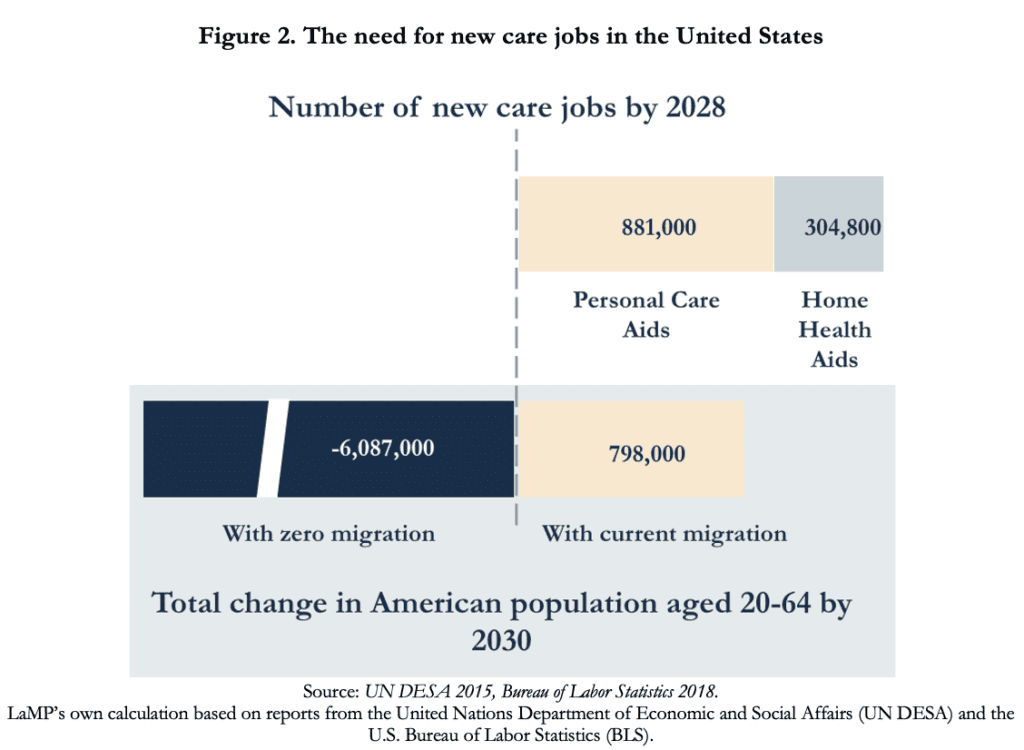

While recruitment difficulties in the LTC sector are linked to low pay, inadequate working conditions and a lack of appreciation for healthcare workers, the changing demographics in OECD countries clearly point to another fundamental problem. As societies get older due to declining fertility rates, their overall workforce shrinks, making it harder for employers to find enough workers to fill the gaps. Rather than “labor shortage,” the more fundamental trend is the one of “labor scarcity.” In the U.S., for example, the number of new jobs in the care sector alone will be higher than the total number of workers in the labor market by 2028. Simply increasing worker wages will not solve this issue.

Although improving working conditions and making the sector more attractive to local workers is an important step in the right direction, the demographic data clearly show that this alone will not fully address the underlying problem. Even with all local workers employed, there simply won’t be enough workers in OECD countries to fill the job openings in the LTC sector.

Labor Mobility as Part of the Solution

It is without a doubt that labor mobility, allowing workers to move across borders in a safe and reliable way, will have to become one of the key instruments within the governments’ tool kit. Currently, less than a handful of OECD countries operate dedicated labor migration streams for care workers. And those that do exist are either often operating at just a small scale or prone to issues around worker exploitation and continuity of care.

Stakeholders around the world have finally begun to recognize the need to include quality labor mobility as part of the solution to labor shortages in the LTC sector. In fall 2022, the European Commission set it as one of its priorities highlighted in the 2030 Strategy for caregivers and care receivers. The Commission will map the current admission conditions and rights of long-term care workers from non-EU countries and consider developing EU-level schemes to attract more workers to the sector.

The GAN call to action also pointed out the importance of staff mobility. Specifically, the providers highlighted the need for sufficient skills and language training as well as countries’ better ability to internationally recognize diplomas and credentials. However, labor mobility as one of the key solutions to labor scarcity has yet to take a major role in the industry’s global agenda despite the indisputable effect it would have on reducing the growing worker scarcity.

Interested stakeholders around the world have already recognized the potential of labor mobility to meet the sector’s needs, taking promising steps towards creating more and improving the quality of migration pathways for the care industry. The Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) successfully piloted two new pathways for workers from Samoa and Fiji to come to Australia, including intensive aged care training before or after arrival. The Germany-based organization Care with Care helps to connect unemployed or underemployed nurses from across the world with healthcare institutions in destination countries with labor shortage, focusing on quality, training and integration of the workers. While the U.S. currently doesn’t have any migration pathway for LTC workers, LeadingAge, a community of U.S. nonprofit aging services providers, proposed the introduction of the “H-2Age” temporary guest worker program for certified nurse aides (CNA) and home care aides.

The Win-Win Scenario

Labor mobility is mutually beneficial for both sending and receiving countries. It helps to solve the worker scarcity in destination countries while promoting the development of poor sending countries. For example, a recent study showed that enrollment and graduation of Filipino nurses had grown substantially in response to increased demand from the U.S. At the same time, the supply of nursing programs expanded. For each nurse that left the country, there were nine additional nurses who obtained their licenses.

A well-designed migration model could provide mutually beneficial solution, supporting the health care sector in sending as well as receiving countries. The Global Skills Partnerships (GSPs) is an example of a program under which some trained workers stay at home while others leave for abroad. As a result, both sending and receiving countries benefit.

Labor mobility must be a key component of any strategy to address worker shortages within the LTC sector. The future of the sector is now in the hands of OECD governments. Finding a solution will not only benefit the LTC providers and workers, but serve a vital role for the aging populations in need for care. The time to act is now.