This post was first published at the Center for Global Development.

Untying’ work permits can reduce workers’ vulnerabilities, strengthen their wages, and improve employer productivity. But these benefits can only be realized if practical barriers to changing employers are removed. Here, we describe how.

Recently, Canada announced they were considering ‘untying’ work permits issued under their Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP). The change would allow foreign workers to move between employers within a specific occupation without applying for a new work permit, rather than being tied to one employer. This change potentially offers improved economic outcomes for employers and workers while reducing worker vulnerabilities; however, because there are so few mobility schemes that allow for this, little is known about how to implement them in practice.

The Benefits of ‘Untying’ Work Permits

Employer-specific work permits render workers dependent on their employers for the right to live and work abroad, minimizing workers’ bargaining power to advocate for better employment conditions. Such issues have been seen within Canada’s TFWP, with reports of wage withholding and poor living and working conditions. This power imbalance is often aggravated by the fact that workers depend on their income abroad to pay off migration-related debts (which, in Canada, were reported to range from USD$4,000 to $10,000 per person).

Changing to occupation-specific work permits could reduce workers’ vulnerabilities, strengthen their wages, and improve employer productivity. However, because so few existing temporary mobility programs (TMPs) have allowed workers to move employers, we know little about the potential impact of this occupational mobility, or even how to implement it.

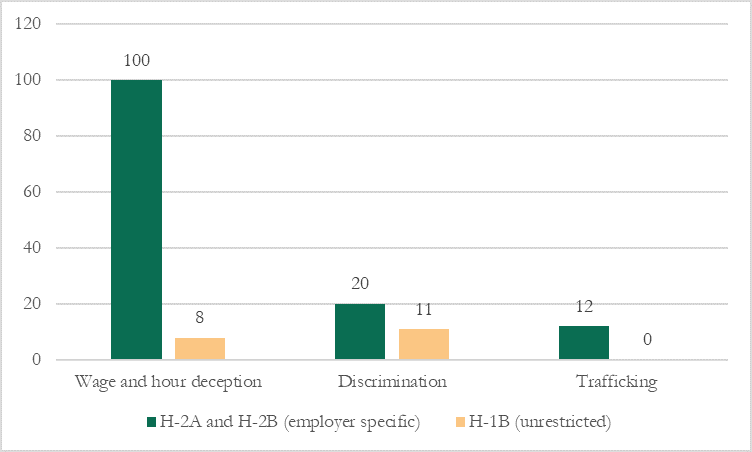

The evidence we do have suggests that when foreign workers are allowed to move employers, there are lower levels of reported abuse, and higher reported wages. In the U.S., occupational mobility led to fewer federal claims for wage and hour deception, discrimination, and trafficking (Figure 1), and higher wages. In fact, one study found employer-specific workers had equal to worse employment outcomes than irregular migrants. Similar results have been seen in the United Arab Emirates (UAE); a 2011 policy reform allowing migrant workers to change employers without prior approval after their initial work contracts expired was found to increase real earnings by more than 10 percent.

Figure 1: Federal Claims in the US were Significantly Higher for Employer-Specific versus Unrestricted Visa Types (1990-2017)

Allowing foreign workers to move employers is better for host country society workers and employers as well. Providing foreign workers with greater bargaining power results in fairer competition within the labor market between them and native workers. Employers can also expect to see increased productivity; short contracts, flat wages, and the lack of occupational mobility means workers on employer-specific visas often have little incentive to expend more effort. In Dubai, this resulted in inefficiencies totaling 6.6 percent of total costs and 11 percent of profits on average.

Realizing these benefits: the necessary underlying conditions

Merely changing visa laws, however, will unlikely be enough to unlock these benefits. Workers need more than the legal right to change employers; they need to be able to do so in practice. There are many barriers to this. From a practical angle, workers may lack information about vacancies, or find it difficult to access job search resources (due to geographic distance or limited access to the internet). They may have difficulty applying to jobs, or an inability (due to mobility or time constraints) to engage in the recruitment process. From a situational angle, workers may be concerned about being dismissed if their employer finds out they are searching for a job. Employers may also be less likely to hire an existing foreign worker over a new one if the administrative burden is too high or if the desire to switch jobs is viewed as a signal of unreliability.

Good policy design can reduce these barriers. The following measures should be followed by Canada, and any other countries considering ‘untying’ work permits.

- Require an occupation-wide labor market impact assessment. Currently, employers under Canada’s TFWP need to conduct a labor market impact assessment to ensure the hiring of a particular foreign worker will not negatively impact the Canadian labor market. Such assessments lead to massive delays which reduce productivity for employers and keeps workers trapped in vulnerable positions which reduce productivity for employers and keeps workers trapped in vulnerable positions. Instead, employers should be required to conduct an occupation-wide impact assessment for approved visa categories. Workers could then transition to any other pre-assessed job within the occupation, without requiring further assessments and without completing a predetermined portion of their initial contract. This somewhat mirrors the design of the Recognised Seasonal Employer (RSE) scheme in New Zealand, where employers are pre-approved to recruit a specified number of workers within a specific sector.

- Include a ‘grace period’. To reduce the risks associated with job searching, an occupation-specific work permit should include a period in which workers can remain in the host country to look for a new job, after their initial employment ends (whether voluntarily or through termination). Mobility schemes for high-skill workers often include such grace periods (such as currently seen in Australia’s Temporary Skill Shortage Visa). Extending this feature to low-skill workers could remove the fear of leaving a job due to abuse or discrimination.

- Offer job search support and auxiliary services, such as an online portal / mobile app with vacancies, and information on the process for employment switching and workers’ rights; dedicated case managers supporting workers through the job search and transition process; and a comprehensive grievance redress system with multiple channels to submit grievances and clear, audited parameters for claims and redress.

Unfortunately, there are few examples of occupation-specific work permits in practice, making it difficult for Canada to know the impacts and practicalities of such a scheme. However, Canada’s history as an innovative leader on immigration policy makes it an ideal candidate for a pilot. ‘Untying’ work permits would likely lead to improved outcomes for Canadian workers and employers, while paving the way for other countries to reap these benefits as well.