This post was first published at the Center for Global Development

To combat a “super-aging” society, Japan plans to admit 500,000 foreign workers by 2025. But the country faces significant implementation gaps, which could be solved through contracting work out.

Japan’s society is currently “super-aging”—the total population is projected to decline by one third by 2065. Faced with a shrinking national labor force (projected to contract a quarter by 2050), the Government of Japan (GoJ) is now turning to immigration.

In June 2018, the GoJ announced a new “Specified Skills” visa, with a plan to admit 500,000 foreign workers in 14 key sectors by 2025. This goal represents nearly a third of Japan’s current foreign workforce of 1.46 million. Yet it significantly underestimates the true labor market need. Outside analysis suggests that Japan needs 6.4 million workers by 2030, 12 times the current goal.

Japan faces significant implementation gaps

More importantly, there is reason to be skeptical that Japan will be able to meet the goal with its current approach and infrastructure. Any temporary labor mobility program needs (at minimum):

- a legal framework creating the right for a worker from one country to be employed in the other;

- infrastructure implementing this framework, enabling workers to secure visas; and

- intermediation services connecting workers to jobs.

In addition to these essentials, protection mechanisms should underpin the entire system to reduce risks for the worker at each stage. Japan faces significant implementation gaps in all three areas.

On the legal framework, despite announced intentions to sign memoranda of understanding with all nine specified sending countries by the end of March 2019, only four were signed (including the Philippines and Nepal). On the implementing infrastructure, the regulations include requirements for a Japanese language proficiency exam and a field proficiency test. Yet as of program start, eligibility tests for 11 of the 14 eligible sectors were still unavailable and many of the foreign testing centers weren’t set up. And on intermediation services, there is a significant backlog in the licensing of eligible recruiting organizations, with only eight of 1,176 applications having been approved thus far. This is exacerbated by a lack of clarity in the regulations, which ban intermediation agencies, while allowing Japanese language institutes in foreign countries to “provide support” to Japanese companies looking for foreign workers.

Even more concerning is Japanese employers’ lack of interest. Only one in four firms plan to hire through the “Specified Skills” visa program, citing costs associated with language learning, training, culture shock, skill mismatches, and housing support as key barriers. A temporary mobility program (TMP) that does not meet employer demand has little hope of addressing the underlying labor market need.

The benefits of contracting out

Given these challenges, how can Japan meet (or exceed) its goal of bringing in 500,000 foreign workers by 2025?

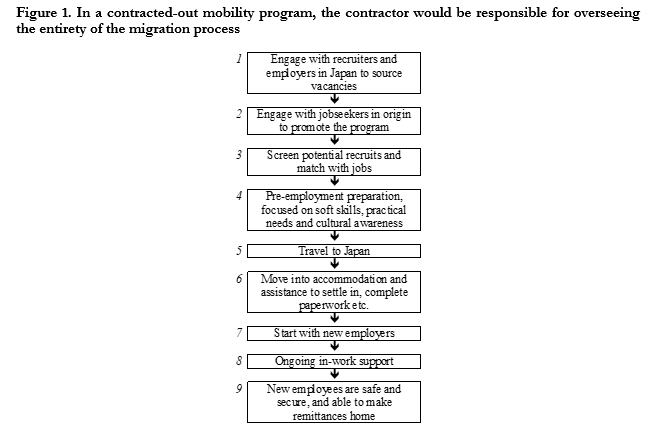

One solution is contracting out to service providers. This has become common in domestic employment services, and is on the verge of being tested in the delivery of mobility programs. In a contracted-out model, a single service provider would be responsible for overseeing the entirety of the migration process (laid out below). While the service provider may sub-contract steps to other providers, this nevertheless creates a single integrated process and shifts a large part of the supervisory burden from the government to the service provider. One example of this model is the Pacific Labor Facility, which is managed by Palladium on behalf of Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

A contracted-out mobility program would:

- Reduce the administrative burden. Both the GoJ and its sending country partners appear to be struggling with the administrative burden of a TMP. While some of these (such as licensing and registration of intermediaries, or issuance of visas) must be fulfilled by the respective governments, many other functions associated with the migration cycle (such as those above) can be contracted out.

- Improve performance of services. Due to their flexibility and expertise, private providers can deliver services which are more cost-effective and perform better (job outcomes and sustained employment) if incentivized by a payment structure that emphasizes outcomes rather than inputs. For example, a “payment-for-outcomes” structure, implemented in the UK’s “Employment Zones” initiative doubled the number of long-term unemployed people securing and sustaining employment.

- Improve quality of services. The government can define and enforce the terms of services through performance management and quality assurance tools, giving it control over both content and impact. Under the current system, the GoJ will need to rely on its regulation and enforcement capacity to oversee the activities of hundreds, if not thousands, of agencies. Under a contracted out model, the GoJ would have fewer agencies to oversee but much more influence, moving from a combative regulatory relationship to a sustainable intermediation partnership.

- Improve demand-orientation. As described above, contractors would be incentivized to deliver results, in this case, workers being matched to job openings. This creates a demand-oriented program, where contractors must work with employers to meet their needs in order to receive payment. Leveraging recruiter incentives to promote foreign workers, and working with Japanese employers to place them, could help address one of the largest barriers to Japan’s current scheme—employers’ disinterest in participating.

- Align the program across borders. The majority of migration systems, including the “Specified Skills” visa, are split between institutions on the sending and receiving side. No matter how well these institutions are aligned, gaps and misinformation invariably remain, resulting in fraud and exploitative costs, poor protection outcomes for workers, and dissatisfaction in job matches for both employers and workers. This can be prevented by contracting out the management of the entire labor migration cycle, including sourcing the job vacancy, sourcing the worker, matching the two, and providing support to both worker and employer throughout the duration of the employment contract.

Of course, using a contracting model requires that there is a sufficient base of quality service providers, AND that the GoJ has sufficient contract management capacity to oversee the program. It also cannot address the current legal and regulatory challenges the GoJ is facing, so it would not be able to make the “Specified Skills” program successful without also building up the regulatory infrastructure. But it would address some of the issues detailed above in an innovative way.

Japan is making a bold change, one that is critical to its economic future. Now it needs to consider how to deliver the program in a way which answers the needs of its employers, while providing valuable and rights-respecting jobs for foreign workers.

One solution: don’t do it yourself; leverage the private sector.