Responsible recruitment has a cash flow problem. In this blog, we present the problem and some ideas about solutions that tie access to finance to responsible practices. Rewarding ethical recruitment by solving cash flow constraints may tip the scales in favor of responsible firms, who have historically struggled to scale.

Imagine you own a small staffing agency that recruits workers from your home state in Mexico and places them in seasonal harvesting jobs in the U.S. each year. You want to serve the workers you recruit well, without charging them unnecessary or illegal fees, and help them get good jobs abroad with good pay (sometimes as much as 20x more than local salaries). The workers you serve are low-income, so fees of a few hundred dollars may force them into debt just to access a job.

Your clients, U.S. farms who employ these workers, don’t pay you for your services until several weeks after the workers arrive on site. But to get the workers to the jobsite, you have all sorts of upfront costs, including staff time, visa fees, and travel and lodging for the workers as they make the trip from their homes. Because your business is small with limited physical assets, you can’t get a loan from a bank to cover those upfront costs. You essentially have two options to get the cash you need to deliver on a staffing contract: (1) ask your clients – the farms – to pay upfront, or (2) charge the workers fees.

Suppose you want to do the right thing and not charge the workers. This may not just be ethical but also makes good business sense because it increases worker loyalty to you and the farm and may be a selling point for farms concerned about their own social impact. You could ask your clients if they will cover at least 75% of your total costs upfront. But most other staffing agencies charge workers fees and therefore appear to offer your clients a better (financial) deal, undercutting you and taking market share. Now what do you do? How can you grow your business? How can you be price competitive as a morally responsible recruiter with limited or no cash-in-hand and reserves?

Limited working capital is a challenge faced by responsible labor recruiters operating in cross-border markets across the world. Responsible recruiters are “double bottom-line” agencies committed to respecting workers’ rights while serving employer clients. They commit to a series of ethical practices and have mechanisms in place to avoid fraud and extortion of workers seeking employment abroad. And as a rule, responsible recruitment agencies do not charge workers illegal or unfair fees.

Because responsible agencies don’t charge workers fees, they are at a competitive disadvantage. Unscrupulous recruiters that charge workers unfair or illegal fees can use this revenue as working capital. In effect, worker fees “solve” the liquidity problem for recruiters, absorbing the risk and debt burden from the firms.This in turn allows these agencies to offer more favorable terms to their clients (the employers), undercutting responsible agencies in the market.

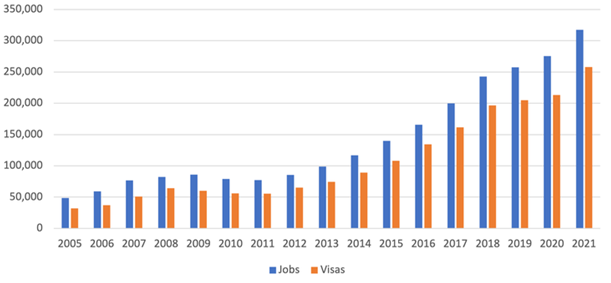

These disadvantages limit the growth of responsible recruitment and have real human costs. Illegal and unfair fees can force workers into severe debt and forced labor situations. Sadly, worker fees, fraud, and exploitation are widespread, and horrific cases all too often make headlines. The problem is only growing more urgent as demand for temporary foreign labor explodes (see Figure 1 for an example from U.S. agriculture) – fueling the expansion of recruitment markets and the number of people at risk of exploitative practices.

Figure 1: The US H-2A program for agriculture, like many other temporary visa programs, is growing rapidly, along with its corresponding recruitment industry

If we want responsible recruitment to scale, we need to solve the challenges facing responsible firms. This includes shifting the financing ecosystem within which responsible agents operate so that they can get the working capital they need to serve workers and employers at scale. Solving this challenge will require new ways of financing and incentivizing international recruitment that encourage capital to flow to responsible agents.

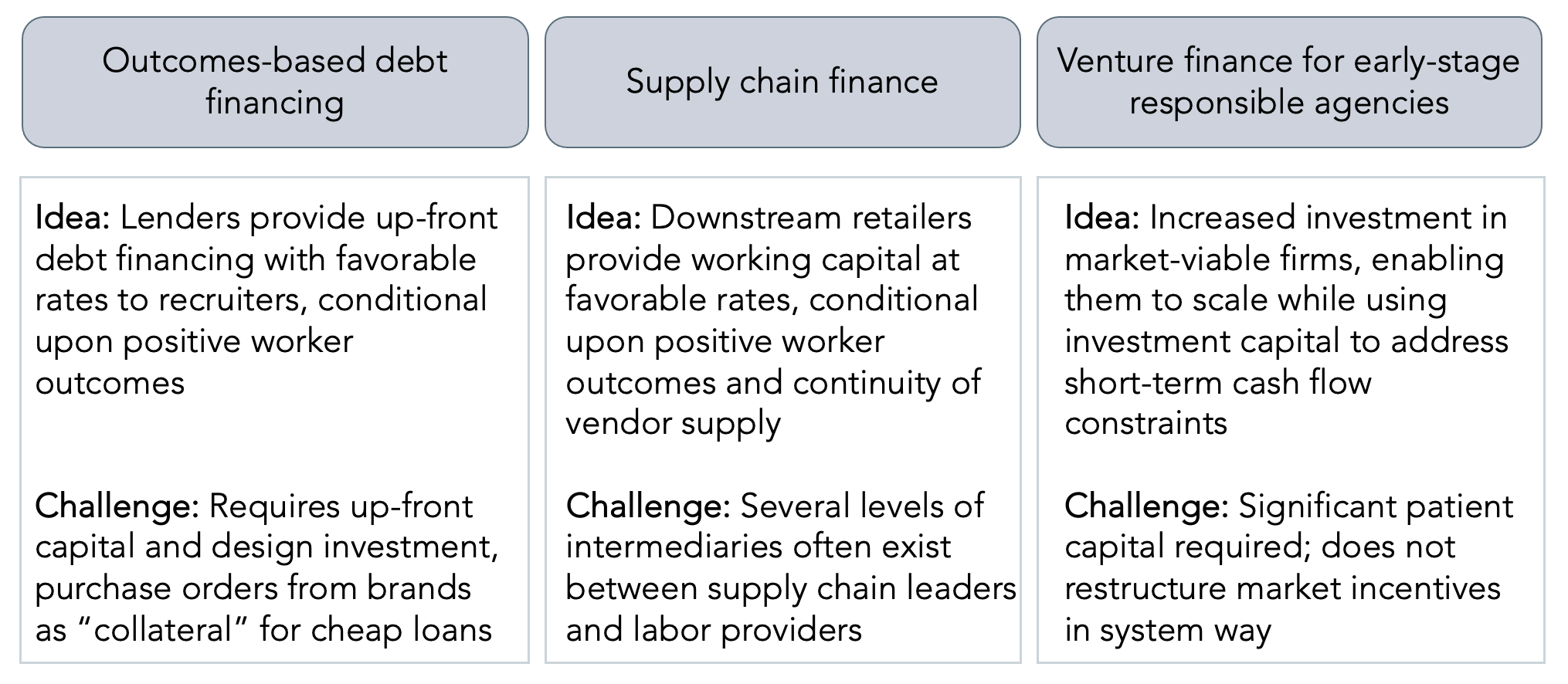

Here are three preliminary approaches that might help move the needle:

1. Blended outcomes-based debt financing could provide responsible recruiters with low-cost loans to cover their working capital needs. Eligibility could be tied to certain quality standards that recruiters must meet. These standards would initially include the demonstration of systems and processes that ensure responsible practices. For repeat borrowers, future loan eligibility could incorporate independent measures of positive worker outcomes from past contracts. This option would most likely attract smaller recruiters or new entrants who have no access to traditional sources of financing and who would benefit from increased market exposure tied to their participation. This approach would require significant philanthropic or patient capital to de-risk or subsidize the loans made to responsible agencies.

2. Supply chain finance models involve commitment of up-front capital by larger, downstream actors (think large retail brands) conditional upon adherence with quality standards and continuity of vendor supply. Assuming the quality standards address unethical labor recruitment, this approach could solve cash-flow problems for recruiters while also reducing the risk of supply chain disruption for the downstream corporations. This model would also transform recruiters into ‘partners’ rather than ‘agents’ of their clients, allowing both parties to plan around and invest in a longer-term relationship defined not only by quantity but also quality. In theory, cheap loans sponsored by supply chain leaders would be attractive to any labor provider or employer. Yet slim profit margins and fierce competition in the industry may limit the pool of brands and retailers who would be willing or able to finance this sort of investment. As a result, this approach may work best in premium markets with clear product differentiation where retailers are more willing to invest in ensuring the supply of specific products (for example, certified organic foods), and in markets where sole-sourcing agreements are common.

3. Increased venture investment would target specific recruiters and invest in those which look especially promising in terms of growth and good practice. Whereas the first two ideas are lighter-touch and open to any recruiter that meets eligibility requirements (either for outcomes-based loans, or for supply chain finance), this third option is a more intensive engagement and ‘eligibility’ would be assessed on a case-by-case basis. This idea would be most likely to work for recruiters who already demonstrate a clear track-record of responsible practices and good potential for growth.

Of course, working capital constraints are just one challenge responsible recruiters face in the market. They may also absorb other risks that ‘standard’ recruiters shift onto the shoulders of workers or employers, such as the risk of failed visa applications, poor job matching, and abscondment. Given the complexity of these challenges, no single solution is a silver bullet. Nevertheless, access to working capital can give responsible recruiters some breathing room, and provide them with the liquidity they need to undertake proper vetting, training, and protection of workers. Quality, alongside quantity, will help ensure that employers, workers, and responsible recruiters alike reap the benefits of efficient and fair mobility pathways.

Getting responsible recruitment right at scale is critical.

Aging populations mean that employers must increasingly look abroad to find the labor they need. At LaMP, we think these trends can be harnessed as a force for good. Workers who move from poorer countries to richer countries can dramatically increase their earnings. For instance, young people who move from Kenya to study and work in Germany may increase their annual income by a staggering 1,563%. This can be life changing. If workers return home, they invest this money in their families and communities. If they can stay, and choose to do so, they still likely send money home as remittances (an important contributor to GDP in poorer countries). And there is evidence that outmigration for work opportunities contributes to a “brain gain” effect in the sending country rather than the feared “brain drain.” In short, the upside of doing international recruitment well is enormous, and the number of lives touched by labor recruitment is only set to increase.

But all these potential benefits are only realized if recruitment systems work for both employers and workers. We’re looking for partners to help us redesign the playing field, so that responsible recruiters have the edge they deserve. If you have thoughts, reactions, or ideas on any of this, please reach out – we’d love to collaborate with you.

The research included in this blog was made possible in part through funding by the Walmart Foundation. The findings, conclusions, and recommendations presented in this blog are those of Labor Mobility Partnerships along, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the Walmart Foundation.