Labor mobility has potential to address worker scarcity in the aged care sector. In fact, providers around the world have been more actively looking into recruiting from abroad. However, lack of available and efficient labor mobility pathways prevents the sector from truly tackling the issue. As policy makers consider opening new and improving existing programs for international recruitment, it is crucial to better understand the experience of foreign-born workers currently employed in the aged care sector to propose actual “win-win-win” policies benefiting employers, workers and ultimately the people receiving the services and the sector overall.

The Ongoing Worker Scarcity

The long-term care (LTC) sector faces dire worker shortages, and the rapid aging in high-income countries stresses the need for more aged care workers even further to accommodate the increase in people needing services and supports. By 2040, the number of LTC workers in OECD countries will have to increase by 60 percent to address the employers’ need. At the same time, estimates show the number of people older than 65 will double from 703 million in 2019 to 1.5 billion in 2050. In other words, one in six people around the world will be at least 65 years old by that time. As a result, LTC providers will need over 13.5 million additional workers in the next 15 years to keep the current care-worker-to-elderly-people ratio.

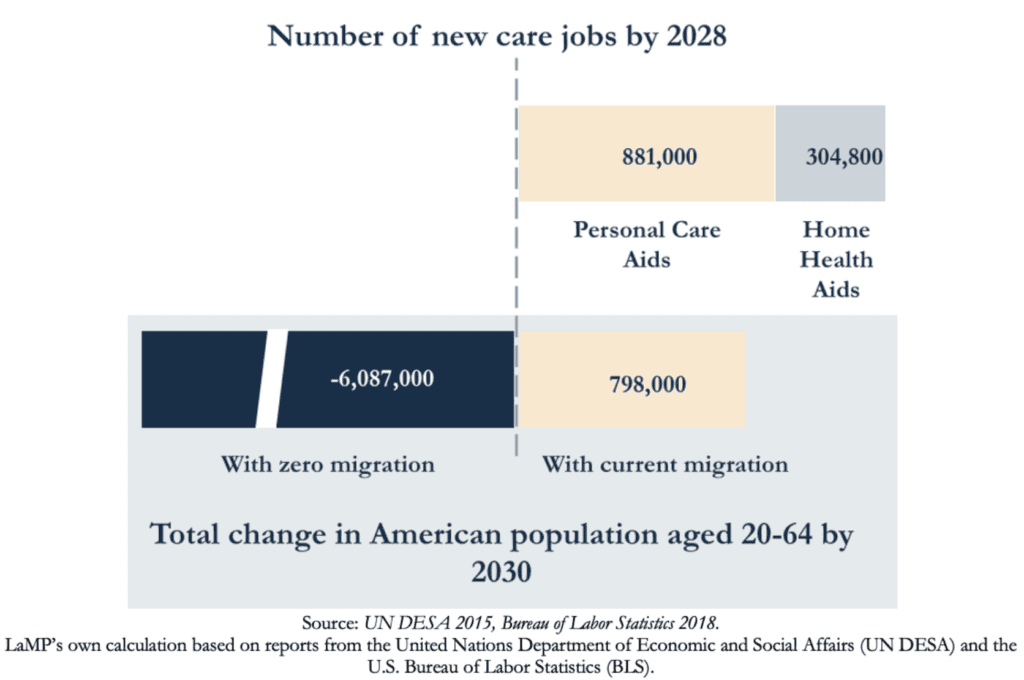

Although increases in pay and improvements in working conditions could address some of the recruitment difficulties in the LTC sector, the changing demographics in OECD countries clearly point to another fundamental problem. As high-income societies continue to age due to declining fertility rates, their overall workforce shrinks. This trend makes it harder for employers to find enough workers to fill the gaps. Rather than “labor shortage,” they face “labor scarcity” that can’t be solved by higher wages or better working conditions. In the U.S., for example, the number of new jobs in the care sector alone will be higher than the total number of workers in the labor market by 2028 (Figure 1.). As a result, the quality of services provided by the sector is at risk of serious decline due to a diminishing pipeline and high burn-out rates among incumbent staff.

Figure 1. The need for new care jobs in the United States

Labor Mobility as a Solution to Labor Scarcity

Effective labor mobility, allowing more workers to receive proper training and move across borders in a safe and reliable way, is one of the key tools to address the issue. On average, over 20 percent of the LTC workforce employed by providers in OECD is foreign-born. That is despite the fact that less than a handful of OECD countries currently operate labor migration streams dedicated to the sector. And those that do exist are either often operating at just a small scale or prone to issues around worker mistreatment and continuity of care.

Data shows well-designed labor mobility is mutually beneficial for both sending and receiving countries. It helps to solve worker scarcity in destination countries while promoting the development of low-income sending countries. For example, a recent study showed that enrollment and graduation of Filipino nurses had grown substantially in response to increased demand from the U.S. At the same time, the supply of nursing programs expanded. For each nurse that left the country, there were nine additional nurses who obtained their licenses. Additionally, effective labor mobility has proven to be the most effective tool to reduce poverty among people in low-income countries. It allows the workers to increase their income as much as 6 to 15 times for their wage in their home country, and the associated remittances and skill accumulation can lead to a powerful positive change on development outcomes in their communities.

However, to design effective labor mobility pathways for the sector, it is crucial to understand the issues and barriers faced not only by employers but also the foreign-born workers seeking better opportunities abroad. To map representation of foreign-born worker voice in immigration research so far, the Labor Mobility Partnerships (LaMP) conducted a literature review which brought a list of only about thirty relevant publications focused on service and trade industries. When it comes specifically to aged care, the literature review concluded that while the demand for foreign-born workers has been documented quite well, research available up to date has not thoroughly explored experiences of the individuals working for the LTC providers in destination countries. Although the lack of dedicated migration pathways discussed above may be complicating the data collection, it is necessary that any proposal for a new migration route for aged care workers considers experience of those currently working in the sector abroad.

What We Know About Foreign-Born Workers in Aged Care

To begin to close the information gap revealed by the literature review, LaMP partnered with the Global Aging Network (GAN) on a survey seeking to understand the foreign-born aged care workers’ experience in high-income countries. While the survey is designed to collect data over time to provide a full picture, the initial results[1] already tell an interesting story of how both the sector and the workers benefit from the ability to work abroad. So far, the respondents, who were mostly (86 percent) female and primarily (64 percent) within the 25-44 years old category, represented 19 countries of origin. Currently, they live in one of the seven represented destination countries, working in the aged care sector mainly as caregivers (63 percent personal aids and 12 percent nurses).

The first round of findings suggests the foreign-born workers are quite happy with their experience in the sector. About 90 percent of the respondents said they are either “satisfied” or “very satisfied” with working in the aged care sector. An overwhelming majority (96 percent) seems to be paid on time and perform tasks they expected before starting the job (90 percent). Over 80 percent of the respondents plan to stay in the sector for at least 5 more years and 65 percent would like to remain abroad.

This seems to be a good news also for the aged care providers. With the broadening workforce gap, employers are looking not only for workers who will take the jobs but rather for qualified well-trained staff, who will stay. The fact that foreign-born aged care workers seem to be quite happy in the job suggests the aged care providers could rely on this group of workers to remain in the sector over time. This is especially encouraging since it is often the employers themselves who invest in and train the new employees.

At the same time, the survey revealed a few unsettling points that the providers should address as they consider hiring from abroad. More than half of the workers (57 percent) reported they work overtime, which 25 percent said is involuntary and for which 39 percent claimed to not receive extra pay. On top of that, some low numbers of the respondents (12 percent) reported they have felt mistreated at their workplace, while 22 percent decided to not directly respond to the question. While no conclusions can be drawn from these numbers alone due to the small sample size and different definitions and perceptions of “mistreatment”, it is worth acknowledging that it seems like not all foreign-born workers have a positive experience working in the sector abroad.

The Need to Hear the Workers’ Voice

Well-designed labor migration pathways could provide mutually beneficial solution, addressing the workforce need of aged care providers in the receiving while supporting communities in the sending countries. The preliminary survey results show that besides helping the employers to fill their openings, a majority of the foreign-born aged care workers (over 60 percent) send money to family and relatives in their respective home countries at least monthly. More than 30 percent consider their family members and relatives to be the main beneficiaries of their experience working abroad. These findings complement the recent global studies showing that labor mobility holds vastly more promise for reducing poverty than anything else on the development agenda. Overall, it is safe to say that employing foreign-born workers in aged care could benefit not only the providers in high-income countries but also greatly contribute to communities in the sending countries.

Any effective labor mobility solution to the worker scarcity in the aged care sector must reflect the needs of not only employers, but also the workers in the industry. Therefore, it is crucial to collect reliable data that will help decision makers to better understand the experience of foreign-born aged care workers as they consider any changes to the current and opening of new pathways.

Therefore, LaMP and GAN will continue the data collection to conduct a broader study highlighting workers’ voice within the industry. Our vision is to assess the more robust information and deliver the final findings in 2025.

This blog was written with a significant support of the Global Aging Network (GAN). Special thanks go to Dr. Robyn Stone, a noted researcher, leading authority on aging and long-term policy and the Senior Vice President of Research at LeadingAge.

[1] These preliminary findings are based only on the first 49 responses to the survey. Due to the small size of the sample, data in this blog do not represent a full picture of the worker voice in the aged care sector. Instead, this blog paints an initial framework, on which GAN and LaMP will build in the coming months as we continue to gather responses to the survey on rolling basis.