Since the global poor have been excluded from earning opportunities in rich countries for so long, nearly all development programs simply assume this is how it will always be. Historically, virtually all poverty reduction and development programs have been focused within the low-income countries, rather than trying to provide the people more and better economic opportunities abroad. And yet, labor mobility holds vastly more promise for reducing poverty than anything else on the development agenda. It allows workers from low-income countries move into higher earning jobs abroad, and thus support themselves as well as their families and relatives back home.

The ongoing demographic changes, resulting in lack of workers in high-income countries and youth bulges in low-income countries, provide a historic opportunity to finally address the single largest driver of income inequality in the world: the birth lottery. The time is now to deploy problem solvers and advocates from low-income, or the “Global South”, countries to start building more and better labor mobility. The alternative includes increasing high-risk irregular migration, labor trafficking, and declining OECD communities and economies.

As the rich world has started to wake up to a future of crippling labor shortages and aging societies, the Global South has a chance to openly advocate for the Global North to open its doors to more workers through expansion of their visa regimes.

The Ongoing Demographic Shifts

Millions of people around the world are trapped in poverty as a result of where they were born. More than half of variability in income globally is explained by country of birth; making it the most important determinant of your opportunity in life and meaning that mostly, “there are not poor people but only people in poor places.”

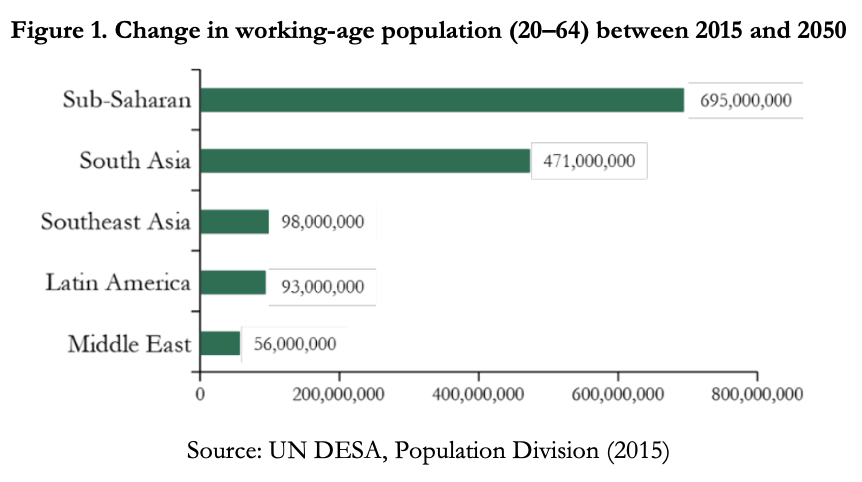

At the same time, these low-income countries of the “Global South” face significant increase in the numbers of young people due to the ongoing demographic changes. Estimates show that the working-age population in these countries will increase by millions by 2050, and in the cases of sub- Saharan Africa and South Asia, hundreds of millions. Within Africa alone, between 10 million and 12 million youth enter the workforce on average each year, but only 3.1 million jobs are created. This poses significant risks associated with youth underemployment, as the governments struggle to create the number of jobs needed to absorb their growing youth populations.

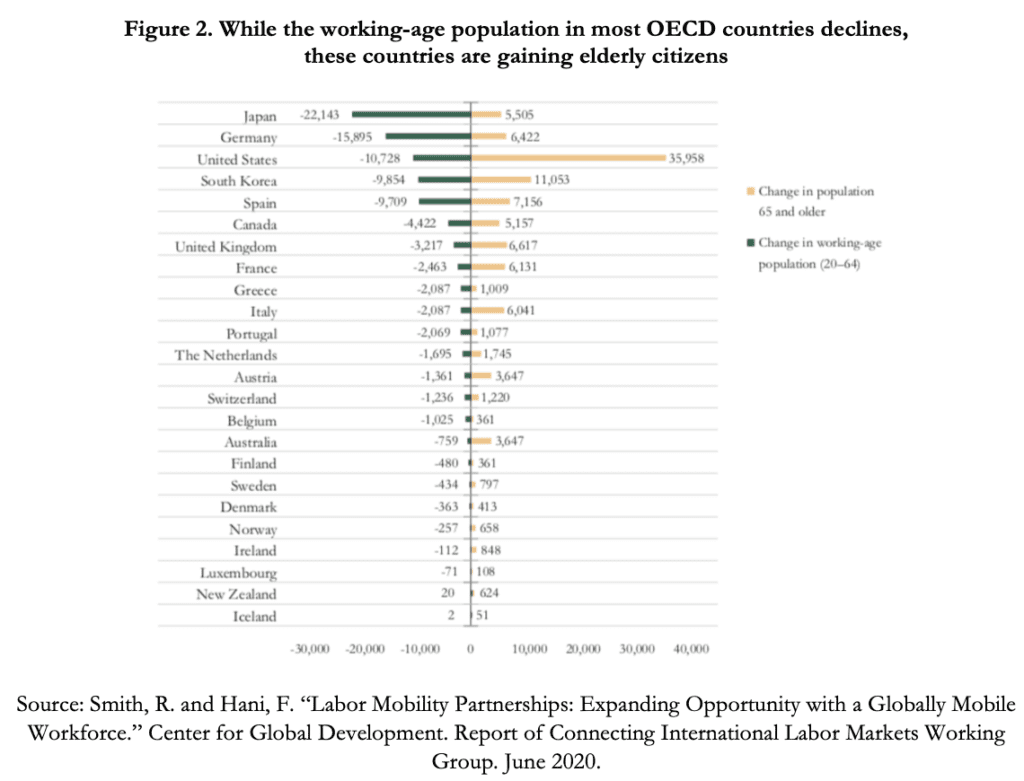

Since the opposite demographic challenge is happening in high- income countries that face crippling labor shortages and aging societies, this also represents a historic opportunity to start building more and better labor mobility. With a shrinking working-age and growing elderly populations, high-income countries will need additional 400 million new workers over the next 30 years in order to maintain their safety nets and economic systems. This massive need for workers offers a path to quality employment for a large share of new working age people from the Global South who are not projected to currently be absorbed by their domestic labor markets.

The two opposing demographic trends provide a historic opportunity to bridge international labor markets. Improving the quality, scale and effectiveness of labor mobility programs between low- and high-income countries can address the labor scarcity – the situation resulting from demographic decline in high-income countries, in which simply increasing worker wages will not address the worker shortage issue. At the same time, such program would help increase the share of youth from the Global South that are engaged in quality employment and providing some transformative benefits for them and their families.

Labor Mobility as Poverty Reduction Strategy

Allowing people to leave their homes to work abroad through quality labor mobility, and thus secure better life for themselves as well their loved ones, has proven to be, the most effective tool to reduce poverty among people in low-income countries. When workers find employment abroad, estimates show they can increase their income as much as 6 to 15 times for their wage in their home country. Overall, implementation of effective policies, allowing for well-regulated migration programs, is far more effective than any other poverty reduction tool. It achieves powerful poverty reduction gains without an upfront investment from governments or donors, unlike other anti-poverty interventions.

Beyond offering quality employment opportunities for their workers, associated remittances and skill accumulation can lead to a powerful positive change on development outcomes in low-income countries. Remittances are as large or larger than foreign aid in many sending countries. In 2021, global remittances estimates stood at USD 773 billion, USD 605 billion of which went to low- income countries. This is approximately at the same level as foreign direct investment (FDI), and when excluding China as the biggest source of external financing, remittances are even larger than FDI. Nepal, for example, was able to reduce its poverty headcount from 45 percent to 15 percent over a 20-year period, despite low growth rates. This was in large part due to remittances, which accounted for 40 percent of the decline in the poverty headcount. The tremendous positive impact of remittances on well-being in sending countries in comparison to other external financing is given also by the fact that they flow directly into households who are able to use them to bolster their consumption and education and health spending.

Workers employed overseas also accumulate skills which they then bring back upon their return home. Return from abroad often allows returnees to capitalize on their acquired skills to secure a more highly skilled job – often with a better salary – than they would have if they had not migrated. As many as half of the skilled migrants working abroad eventually come home, bringing these new skills and connections with them. As an example, returnees to Brazil, Chile, and Costa Rica have been overrepresented in highly skilled occupations and underrepresented in least-skilled trades. This challenges the traditional ‘brain drain’ claim that skilled migration depletes the stock of human capital in sending countries and hurts their prospects of economic development, an argument that has often been a barrier to sending countries engaging on labor mobility.

Why Have Global South Countries Not Advocated for More Migration Programs?

Despite the positive benefits of migration programs, low-income countries have not been widely vocal in calling for labor mobility to expand opportunities for their people. Several factors have been contributing to the skepticism about labor mobility although as shown below, these concerns have not proven to be valid.

First, since government officials in low-income countries often view promoting labor mobility as a way to a better life for their people, it is perceived as admitting failure of their own development as migration is commonly believed to reduce with rise in income. However, this belief is not supported by evidence, which instead has shown an ‘emigration life cycle’ in which migration first rises, then falls as GDP per capita increases in low-income countries.

Second, a key concern among sending country governments is the risk of worker abuse and violations of their rights. This has concretely manifested as a political and reputational risk in sending countries, where cases of worker abuse have had direct and strong repercussions for government officials. Many times, such as in the Philippines, Ethiopia and Indonesia, cases of worker abuse have resulted in a complete ban from the sending country on recruitment of workers to a particular receiving country. However, these bans have largely served only to encourage even more risky irregular migration; for example, within two years of Ethiopia banning labor mobility to the UAE, as many as 30,000 Ethiopians were detained there for irregular migration.

Third, concerns around ‘brain drain’ are another reason low-income countries choose to not pursue labor mobility as an employment strategy. However, evidence shows more of a ‘brain gain’ than ‘brain drain.’ Migration opportunities increase earning potential within specific sectors, which in turn increase the return to skilling in that sector. This creates demand for training in this sector, which results not only in the emergence of specialized schools and vocational training institutes, but incentivizes more people to train than actually migrate. The most vivid example is the Philippines, where the migration of nurses increased the country’s stock of nurses and nursing enrollments increased so much that for every trained nurse who migrated, 10 additional nurses were licensed.

It is the Perfect time for the Global South to Begin Advocating for More and Better Labor Mobility

All the factors mentioned above contribute to the common belief that labor mobility as a solution to the ongoing demographic changes is politically impassable. Sending country officials with mandates to open new foreign labor markets for the country’s workers report the primary constraint to be knowing which countries to approach and, within those countries, which individuals and government bodies to approach and how. This ultimately leads to competition between sending countries that are trying to attract and convince high-income countries to open more pathways for their workers, resulting in hampered overall benefits and lowering of labor mobility standards.

However, it is clear that if the Global South countries are committed to the well-being of their people, they should consider labor mobility a viable and positive strategy. Bridging their labor surpluses with significant labor shortages in high-income countries alleviates risky employment pressures from their growing youth populations. Meanwhile, they stand to benefit from increased inflow of remittances and skill accumulation, both of which are powerful forces for bettering living standards in sending countries. However, all these benefits are lowered by the ongoing competition between the sending countries.

The ongoing demographic changes provide a historic opportunity for the Global South to build a coalition openly calling for a dramatic increase in the number and quality of labor migration opportunities in the high-income countries. Such cooperation would allow the sending countries not only to increase their bargaining power with the high-income countries, but also provide space to share lessons learnt and collaborate on creation of labor mobility programs. Ultimately, it could help unlock more life-changing opportunities for millions of workers from low-income countries and their families.